The ThermoWorks Guide to Everything You Need to Know About Steak: Temperatures, Ordering, and Buying

When Americans go out to celebrate, there’s usually one thing on their minds: Steak. Whether at a mega-chain steakhouse or a high-end, gourmet restaurant, people often reach for a big, juicy steak when they have a reason to splurge. And why not? If you’re going to a fancy restaurant, why not order the most expensive piece of meat on the card?

But there is a problem with so many people eating steak only for special occasions, and that problem is that many of those people only go out to eat for those special occasions. Chances are if they usually go out, it’s not to a fine-dining establishment, and when they arrive at one they might feel uncomfortable with the menu. Such customers aren’t usually the adventurous type. They’re not likely to order the Chef’s roast duck leg with parsnip ragout and orange-flower water raspberry gastrique. They want something familiar, something comforting, something that says fine dining and high class without involving too much risk. Many of them opt for steak. In professional kitchen lingo, these diners are known as amateurs.

Now, you are not one of them, but if you go out to a nice restaurant, they are out there and you will reap their sowing. Amateurs inspire most kitchens to put a steak on the menu, and if you order the steak, those kitchens might make a statistical assumption that you don’t know what you’re doing when you order. So if you want to make sure you don’t get the short end of the steak when you go out for a nice dinner, you need to be able to order steak like a pro, and that’s what we’re here to talk to you about today.

Welcome to our Guide to Steak. Whether you’ll be joining the hoards at the fine dining establishments or searing up your own juicy cuts at home, we’ve got you covered. We’ll review the different cuts of steak, steak doneness temperatures, of course, and even how to pick out a steak at your local butcher or grocery store. So settle in, things are about to get meaty.

First Things First: Steak Temps

Let’s first lay down some science to build on. Meat is made of muscle fibers. Those muscle fibers are bundles of various kinds of protein fibers. When those proteins are heated past a certain point, their shape changes in a process called “denaturing.” This is what cooking meat is all about. By applying heat to the meat we fundamentally change its structure and composition, thus altering flavor and texture until a raw piece of meat becomes palatable.

When the protein fibers in meat reach 130°F (54°C) they begin to tighten, coiling up and packing themselves more tightly. As the proteins coil and tighten, they expel water, like a sponge being wrung out. The hotter the temperature above that 130°F (54°C) threshold, the tighter the squeeze and the more water lost.

If you heat a steak beyond to 140°F (60°C), the red myoglobin in the meat will start to denature and turn a darker, grey-brown color. The long protein fibers will move beyond tightening and start to shrink, expelling even more water.

And this brings us to the steak doneness. When your waiter asks you how you’d like your steak done, don’t answer by saying that you’d like it “with some pink.” “Some pink” isn’t a measure of actual doneness, and, to be frank, requires someone to cut into your steak to peek inside.

Order with the standard system of rare, medium-rare, medium, medium well, or well-done. I’ll go into these gradations in detail below, but first I want to make something very clear: based on what we’ve just gone over above, if you don’t want to sound like an amateur, don’t order a steak that is both well done and then complain when it isn’t juicy! No amount of cooking skill can overcome the physics at play in the protein structure of the steak.

Steak Doneness Temperature Chart

| Preferred Doneness | Degrees F | Degrees C |

|---|---|---|

| Rare | 120-129°F | (49-54°C) |

| Medium Rare | 130-134°F | (55-57°C) |

| Medium | 135-144°F | (58-62°C) |

| Medium Well | 145-154°F | (63-67°C) |

| Well Done | 155-164°F | (68-73°C) |

It is important to note that the temperature is the key to doneness, not the color. So while I describe the coloration of each doneness below, keep in mind that there are other factors that can affect the color of the meat regardless of actual doneness. It is possible to have a medium-well steak that is quite

(For more on steak doneness, see our article on steak temps.)

Rare steak temp 120–129°F (49–54°C)

A rare steak is usually very red in the center that can still be cool to the touch. It is just past raw in the center and has a texture that is not everyone’s cup of tea. The flavor, undeveloped by cooking, can be somewhat iron-y.

Medium-rare steak temp 130–134°F (54–57°C)

Medium rare usually has a warm red center. This is widely acknowledged as the sweet spot of juiciness and texture, providing the diner with a pleasant mouth-feel, good flavor development beyond rare, and less “ick” factor for some.

Medium steak temp 135–144°F (57–62°C)

The center of a medium-cooked steak is very warm and is usually pink, not red. It will be firmer (read: tougher). It will seem juicier, in that when you cut it, juices will run out of it. But those juices have been squeezed out of the fibers. So while you will see juices on the plate, the steak itself will have a slightly lower water content in the meat and be drier and chewier.

Medium-well steak temp 145–154°F (63–68°C)

This is where things really start to change quickly. The protein fibers in the muscles shrink dramatically and the steak loses much of its volume. (The truth is, if you order a steak medium well, no matter how much you actually like it that way, the kitchen will think you have no idea what food is supposed to taste like. It’s not fair, but it’s how it works.) This steak will usually be just slightly pink in the center and will have lost much more of its juices to the fire.

Well done steak temp 155°F+ (69°C+)

At this doneness, the proteins in the steak are completely denatured and the natural juices are drained. Most of the tenderness is gone and any that remains is only due to the lack of connective tissues. With almost no native liquid left in the meat to carry its flavors to the remotest corners of your mouth, it is harder to get the full flavor of the beef. That being said, many people do like their steaks cooked this way and, while we disagree, we wish them well.

It’s worth knowing, by the way, that you will make the kitchen staff angry if you order a quality steak well done—not only because they consider it to be a waste of the food itself, but also because on a busy night—maybe a weekend or some other important dining-out night like Valentine’s Day—you’re also slowing down the line, holding up other reservations, and generally throwing a wrench in the gears.

When you order your steak, it is best, in most situations to order it simply according to the above levels. Don’t say “medium-rare plus.” That’s not a thing. Medium rare is only 5°F (2.8°C) wide. If you try to put a “plus” on that in a busy service, you’re getting medium.

Even better, of course, is to order your steak exactly to temperature. Not all kitchens will be equipped to handle this request, but it’s worth a shot. I like my steak to come off the grill at 125°F (52°C), and I’ll even ask for it that way when dining out. If the waiter looks at you like you’re s

Carryover cooking in steaks:

The temperatures listed above are final temperatures. Because of the high-heat cooking environments for steak, it’s best to pull them about 5–7°F (3–4°C) early to allow for carryover cooking. You don’t need to tell your waiter that, but you do need to know it if you’re cooking at home!

Buyer’s Guide to Steak Cuts

Of course, staying home and cooking dinner yourself is a great idea, too. To be honest, you can probably make a steak that is every bit as good—nay, even better than—most of the steaks you will get at a busy restaurant. Here we’ll talk about the most common steak cuts and what to look for when you buy a steak to cook at home. Just remember to use the temperature guide above and the Super-fast® Thermapen to cook your steak to your perfect preferred doneness.

Beef grades: what do they mean?

To buy a good steak, you need to understand what the grades of beef mean and what they don’t mean. The USDA established beef grading in 1917 to ensure quality beef was being shipped to the front during WWI. It later continued the practice to ensure quality on steamships and railcars. The grading system has undergone changes since the early 1900s, though many of the terms we use now were established by the early 1940s. Though inspection for “wholesomeness and safety” is mandatory and carried out by the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), meat grading is voluntary and paid for by the producer.

The grading system you encounter as a consumer has two basic parts: a letter grade indicating the age of the animal and another grade that indicates the level of marbling.

Though it is less common to see it in meat cases or at butcher shops, the letter grade indicating age is useful. If your meat department labels it, know that Grade A beef is from an animal 9 to 30 months old, Grade B from 30 to 42, on down through Grade E, which is over 96 months old. Highest quality beef is usually Grade A.

Marbling scores, what we commonly know as steak “grades,” are given to determine the “palatability” of the beef, a term that includes tenderness, taste, and the

The highest grade is Prime, followed by Choice, Select, Standard, Utility, Cutter, and Canning. Prime beef has the most inter-muscular fat marbling, followed by choice, and so on.

Below you can see a comparison of two strip steaks: one prime grade, the other choice.

From the USDA website we can learn about the grades and how they are used:

- Prime grade is produced from young, well-fed beef cattle. It has abundant marbling and is generally sold in restaurants and hotels. Prime roasts and steaks are excellent for dry-heat cooking (broiling, roasting, or grilling).

- Choice grade is high quality, but has less marbling than Prime. Choice roasts and steaks from the loin and rib will be very tender, juicy, and flavorful and are, like Prime, suited to dry-heat cooking. Many of the less tender cuts, such as those from the rump, round, and blade chuck, can also be cooked with dry heat if not overcooked. Such cuts will be most tender if “braised” — roasted, or simmered with a small amount of liquid in a tightly covered pan.

- Select grade is very uniform in quality and normally leaner than the higher grades. It is fairly tender, but, because it has less marbling, it may lack some of the juiciness and flavor of the higher grades. Only the tender cuts (loin, rib, sirloin) should be cooked with dry heat. Other cuts should be marinated before cooking or braised to obtain maximum tenderness and flavor.

- Standard and Commercial grades are frequently sold as ungraded or as “store brand” meat.

- Utility, Cutter, and Canner grades are

seldom,

— USDA, https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/food-safety-education/get-answers/food-safety-fact-sheets/production-and-inspection/inspection-and-grading-of-meat-and-poultry-what-are-the-differences_/

The grading of beef says nothing—at least not anything directly—about how the beef was fed or raised. Grass fed beef tends to be leaner than grain fed beef, so it will not usually receive high grades like prime. If you want to ensure that beef is handled a certain way, the grading will not tell you. You have to get to know the sources for the beef itself. Getting to know a local producer or small-scale butcher is the best way to learn more about how your beef is produced.

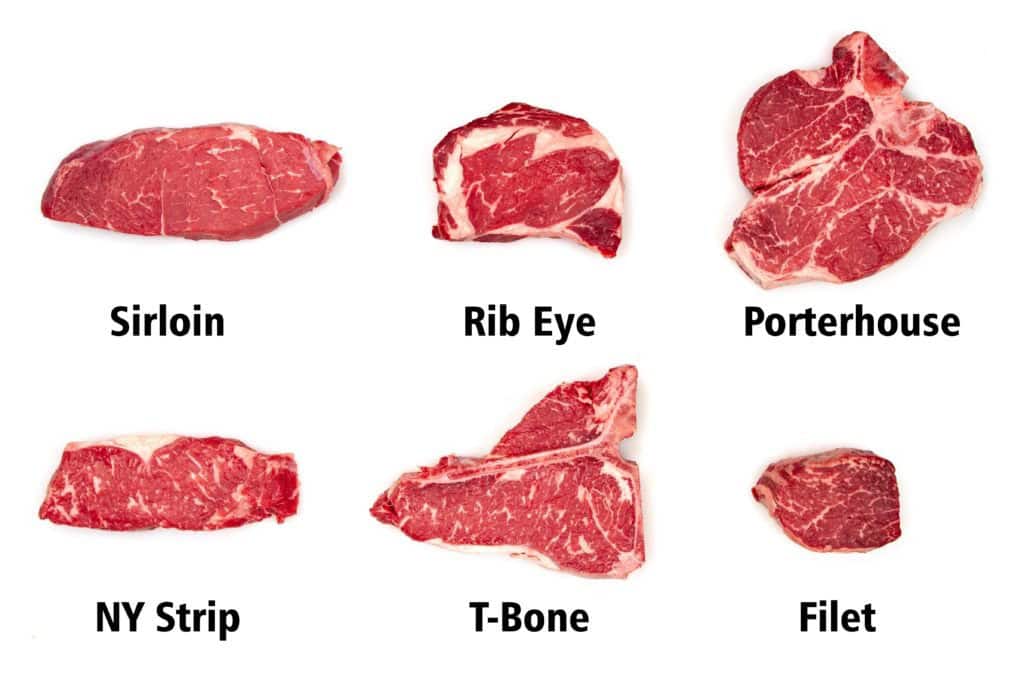

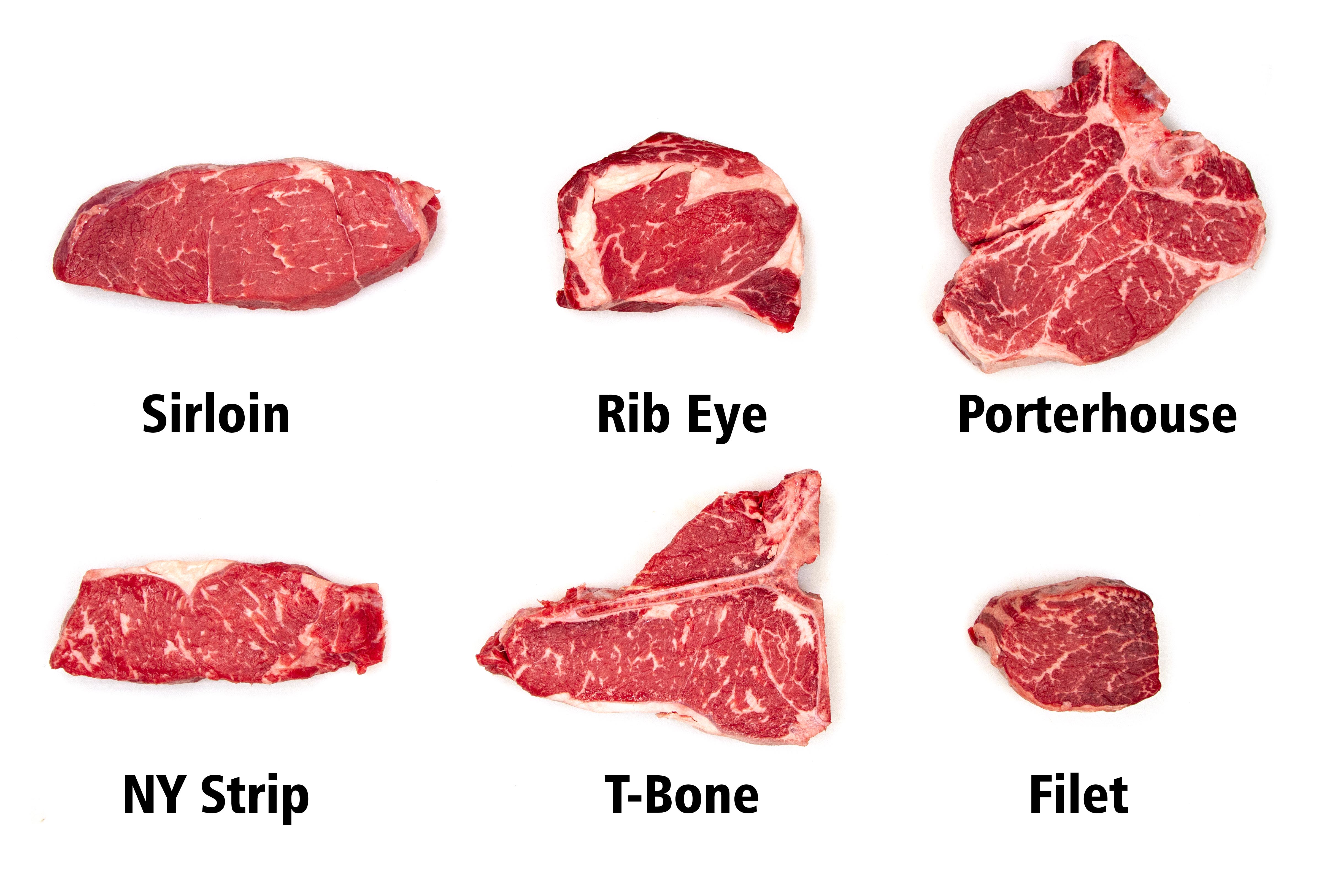

A guide to steak cuts

Let’s take a look at the major steak cuts now, so you can know what to look for and what to avoid at your local butcher or meat department.

Sirloin

The sirloin is the old-school steak—the big man, big hunger steak of our grandfathers. It comes from the rear half of the loin and, while tender, isn’t as tender as its neighboring cousin, the strip steak. The sirloin is also rather vague when it comes to quality: the sirloin section of the cow offers steaks of various constitutions, depending on their location. Top sirloin is of very good quality and is very tender, while bottom sirloin is tougher. Many sirloin steaks have a gristly membrane running through them, making them less appealing (and therefore somewhat cheaper) than some other cuts.

Sirloin is also rather lean, which is good if you are trying to eat more healthily, but also means that it has less resistance to overcooking. (Inter-muscular fat acts as a buffer against overcooking by melting and contributing to a pleasant mouth-feel. Leaner cuts must be more wary of exact temperatures than fattier cuts.)

If you want a big piece of beef that is pretty tender and has good beefy flavor, but also doesn’t break your budget, sirloin might be right for you.

Rib eye

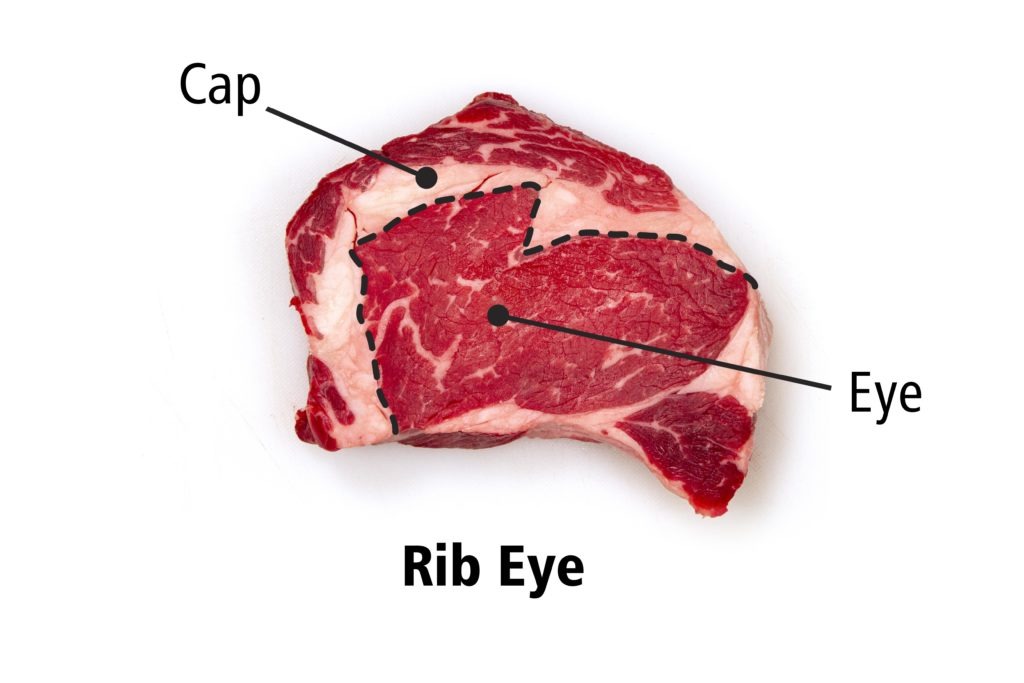

Ribeye is one of the great cuts on the whole cow. It’s well marbled with fat and has large deposits of fat that contribute to the richness of this steak. The fat in a rib eye is particularly tasty, with a characteristic drool-inducing flavor and smell. Rib eye can be purchased either bone-in or boneless. If you like very large cuts get a tomahawk steak, which is a very thick rib eye with a long bone attached to it.

The rib eye steak is composed of two main muscles, the eye and the cap. The eye is meaty and tender, but the rib eye cap is a true delight. It has a tender, almost soft/spongy texture and a deep, intense flavor. When shopping for a rib eye steak, look for something with good marbling in the eye and as thick a cap section as you can find.

If you want a fool-proof method for cooking them, try our tips for smoking and reverse searing your rib eye steak. (If you don’t want to smoke it, use the same two-step procedure in your home oven.)

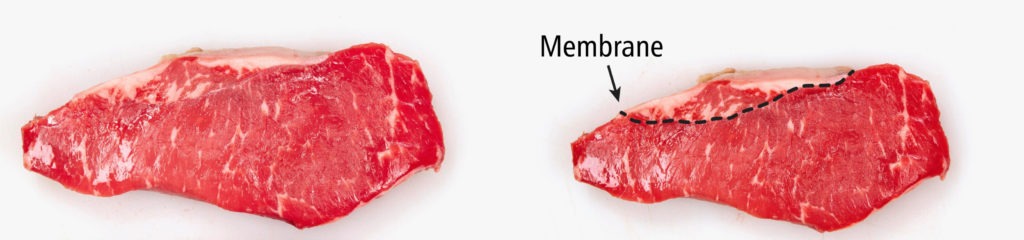

(New York) strip

The strip steak comes from the “short loin” of the steer and is widely beloved. A nicely portioned, meaty strip steak is a joy to eat, with good tenderness and sharper, beefier flavor than the ribeye or the filet. Strip steaks can be prepared either bone-in (Kansas City strip) or boneless (NY strip). The same principles apply to the strip as the ribeye when it comes to bones.

When looking for a strip steak, look for a uniform appearance to the meat, with the grain not seeming to switch directions halfway across the steak. And, if possible, avoid steaks that have an “eye.” The eye is a section of meat that is offset by a gristly, chewy membrane.

In general, a strip steak is a great choice that is neither too fancy nor too plain. To learn more about cooking it right, look at our post on NY strip steak temps.

Filet mignon

Ah, the filet—the gem in the crown of the steak world. The filet (also called filet mignon) is cut from the beef tenderloin. If you want to save money and get several good steaks, I recommend you do a little home butchering and following our instructions for cutting and cooking your own filet mignon steaks.

The filet is über tender, with a texture that is often, and with only slight exaggeration, described as being like butter. Its one flaw is that it is quite mild tasting. There is less sharp beefiness from the meat itself and it has none of the deep richness of the rib eye. Without a good sear, the filet can be pallid and boring. With a good sear, it is a treasure.

Of course, filet is one of the most expensive steaks. You get about 12 good filets from a whole cow, and that is reflected in the price.

When buying a filet, look for the most marbling you can find, and be wary of any seams you may see in the meat. If there is a membranous seem, they’ve probably cut too far into the chateaubriand section of the tenderloin, and you’re getting some chewier bits.

Note that a filet should never really be cooked past medium-rare because it is quite lean and the texture suffers badly when it is cooked even as far as

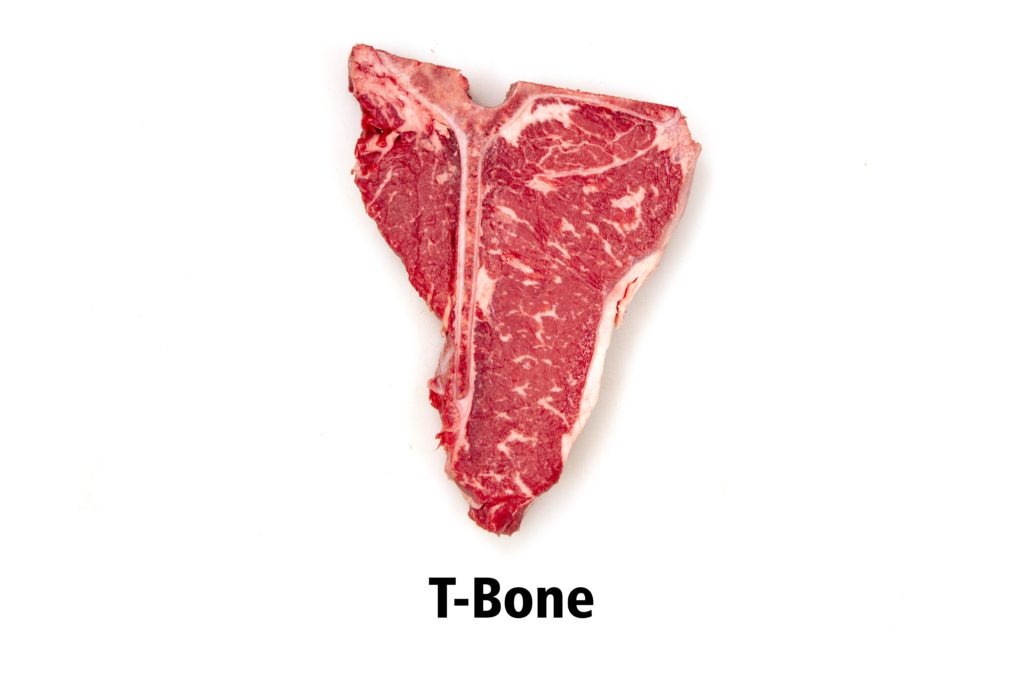

T-bone

The T-bone steak is where steaks start to get even more extravagant. It is composed of a strip steak, the accompanying bone, and a little bit of the tenderloin on the other side. It is, in fact, a Kansas City strip steak with a bite of filet. These steaks are large and celebratory, evoking prosperity and fullness. They can be challenging to cook properly, because the filet bit will tend to overcook while the strip section is still coming up to temperature. Careful temperature management and a two-stage, reverse sear cook is really the way to go for this and the porterhouse.

When shopping for a T-bone, try to get the biggest section of tenderloin that you can. Be sure that the bone is cut evenly, with no bits sticking up above the surface of the meat which would prevent the steak from lying flat in a hot cast-iron pan. (That shouldn’t be a problem usually, but watch out for it!) Of course, you can always grill it!

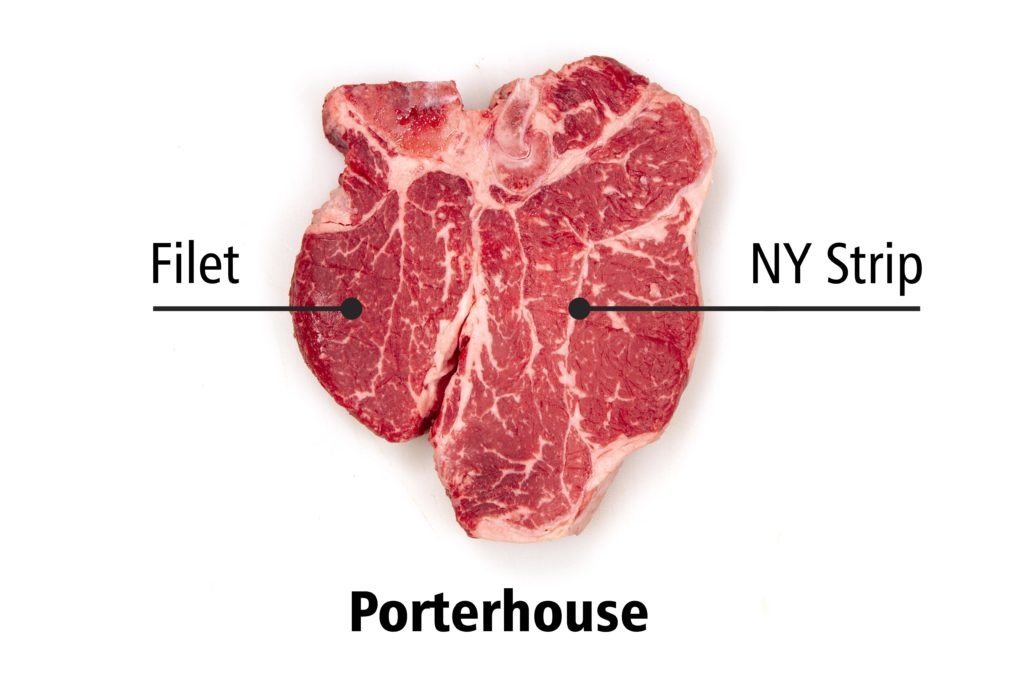

Porterhouse

The porterhouse is a T-bone on steroids (not literally). Where the T-bone is a strip steak with a little filet thrown in for good measure, the porterhouse is a strip steak with a whole filet attached. It is two steaks in one, and that explains why it feels like you pay for two steaks when you buy one of these!

As mentioned above, there is some difficulty cooking the two different muscles properly. If you must err, err on the side of perfecting the tenderloin section. Again, a reverse sear is probably the best way to assure perfection with the porterhouse. But other methods do work very well. In fact, we also recommend broiling your porterhouse!

Because of its location in the loin, it is hard to find a porterhouse with a large section of filet that doesn’t also have at least some “eye” on the strip section. Look for a steak with a good balance between a large filet and a small eye, and, as always, good marbling.

The porterhouse is huge, and therefore a great steak for sharing.

Steak thickness

A word on steak thickness. Many grocery store meat departments offer “deals” on steaks that look appealing—usually something like an 8 oz steak for $6. This seems like a great deal because it’s a steak dinner for six bucks, but those steaks are often very thin—maybe even as thin as ½-inch. It is very hard to cook a thin steak correctly. By the time you’ve seared both sides, it’s already cooked to well done in the middle. For a properly seared steak with good flavor, you should get steaks that are at least one inch thick. This is true for all cuts of steak. That might mean buying a steak that is too big for you to eat all by yourself, but you can always share one large steak between two people.

Whew! That’s a lot of information about steak, and it may seem overwhelming, but there are just a few key things to remember.

- Always buy the best beef you can afford. Prime beef tastes better than choice grade, and

choice is better than select. That makes your meal thatmuch easier to get right. - No matter what grade you buy or what cut you choose, remember that it is not time or color that determines the doneness of a steak, but the internal temperature. Whether it’s sous vide cooking, grilling or searing your steaks, or just ordering steak in a restaurant, know your preferred doneness temperatures.

- Tools like the Thermapen enable both you and your chef to have the control needed to cook steaks perfectly every time.

Get those things right and you can celebrate any day with meat done right, courtesy of ThermoWorks.

This has all been about “regular” steaks, because this wasn’t a good place to talk about Wagyu beef. But we’ve covered How to Cook Real Japanese Wagyu, also! Check it out.

Shop now for products used in this post:

Thank you for all the info on steaks. No one has ever explained the different cuts to me before.

I found the info on the different cuts and how to best cook them very helpful.

Chef, thank you for the detailed discussion regarding steak. Although I thought that I was knowledgeable about steak, you provided great insight for me – particularly the grading of beef.

Paul,

Thank you! I hope the newfound knowledge is useful to you!

Outstanding detailed description. And the photos were very helpful.

I’ve never read anything more informative on steaks.

Nice informative article.Being a meatcutter all my life I rarely [no pun] order steak out. Period. Too many variables make up the end product on the plate. Treat yourself. Learn to cook “em, and get to know a couple of nice meatcutters. If you do order out, that’s cool. I know a lot of owner, operator, chefs, and I say support your local people. All my life I’ve miss out on somebody serving me a perfectly done steak with all the trimmings in a nice setting. Why? because I’m big headed. Nobody serves me a steak better than I do. That’s OK, I don’t have the time, ingredients or know how for good Italian, Chinese … But I know some great local places that do. You get the point!

Stanly,

Thanks for your input! It is true that once you learn how to cook a great steak, eating them at restaurants…well, it’s just not the same! And you’re right that getting to know a meatcutter or a good, local chef is the way to go.

Happy cooking, and happy eating!

I’m 69 and love a good steak. This is the best article I ever read. Thank you

Very informative. I’ve been eating steaks for over fifty years now and it is surprising how little I know about them.Thanks, Clayton

Great steak summary!

I enjoy all these articles but found this one to be especially valuable. Well written with excellent pictures.

a very informative article! Now I just have to learn the proper methods and estimated times for cooking steaks. I would hate to ruin a good cut of meat or poultry for that matter.

Gary,

The estimated times will take trial and error for each kind/thickness of steak and each method of cooking. If you want to be able to know about how long it takes, I recommend getting a timer like the TimeStick and timing a few cooks. Write the times in your recipe, and next time you’ll know about how long to plan so you can get dinner on the table when you want it.

Happy cooking!

Great article! A wealth of information, logically and well presented. I will be sharing this.

that was a very,very good article. it has all the important info a person should know, thank you.

Great information, I will try to remember it all and follow the instructions. Thanks for all the help. This should make for a very happy WIFE and that makes for a great life.

What an excellent and informative article which answered questions that I have had forever! Thank you much for putting this out there!

Very informative article. You were particularly kind when you talked about the kooks who prefer their beef well-done! The only puzzling thought I still have is how/why one store’s USDA Choice rib-eye tastes better than another’s. Additionally, when you speak of steak thickness, is there a point at which the steak may be “too thick” for grilling? Finally, regarding your Thermapen: Is the “don’t ever use a fork on a cooking steak” adage in consideration it the Thermapen’s use? How about how/where to insert it into the steak?

Again, this article is great, and I thank you.

Robert,

Thank you for reading, and those are great questions.

First, grading and stores. As I alluded to in the article, grading determines only one aspect of meat quality, running with the assumption that other characteristics will follow from that one measurement. But there are other factors that aren’t recorded in the “choice” labeling. Of instance, breed of cow. Angus is very popular, but it has different characteristics from, say, a Hereford. Not every meat counter will know the breed of cattle.

Another factor is the slaughter and packing process. While there are standards for cleanliness and wholesomeness that are set and inspected by the government, there are better producers and less good ones. Chances are, you’re getting something akin to what you pay for. Cheap beef may come from cheap cattle or a less-than-quality packing house.

When it comes to thickness, you really just need to consider the method. A 3″ thick ribeye (aka a small prime rib roast!) can certainly be cooked on the grill, but you will absolutely need to use a two-stage, reverse sear method. Cook it on indirect low heat until it is within about 10°F of your desired pull temp, then move it to sear over hot coals/gas.

As for sticking a steak with a Thermapen, we’re planning on putting that myth to rest soon with some real science. Suffice it to say that the amount of juice lost by sticking a steak with a Thermapen is less than you’d lose by overcooking the steak! The juice lost from it is minimal.

But! to minimize the loss, take the temp by going in from the top of the steak, down past the center, and pulling it up through, looking for the lowest temp on the Thermapen. By going in perpendicular to the surface, you create the smallest hole in the meat. Going in from the side creates a long tunnel of moisture loss.

I hope that all helps, and that you become an expert at steaks!

Thank you. You guys are the greatest!

I’ve always felt the T-Bone to be a superior cut as the Porterhouse almost always has an eye in the Sirloin section.

Ronald,

A very valid opinion! To me it’s worth the eye to get more tenderloin, but to each his own!

Great article. Coming from a farm family on both Dad and Mom’s sides it is good to remember your meat selecting, cooking and ordering points. I find that it actually helps in beef, lamb and pork selection.

There is one more very important point especially in buying beef. That is how long the carcass has been allowed to hang (aging) in the butcher’s cold box before it is processed into different cuts. We always told our local meat locker (butcher) to allow a minimum of 30 days. Usually the longer, the better. Toward 40 was great. When I was young: 1950’s 60’s early 70’s, it would be no problem to ask for this amount of time. Now it is nearly impossible because of butchering expenses and locker space. Grocery stores, unless it is a specialty shop, won’t have these meats on hand. I tend to look for steaks that have been sitting in the display case longer than the others which sometimes give away their time by the color/darkness of the meat. Not always an indicator, but sometimes ……

Brennan,

Have you considered buying primals or sub-primals and aging them yourself? I know there’s a lively community of DIY beef agers on the internet, and with some ThermoWorks thermometers and hygrometers (humidity meters) you could get that 30 age you like so much!

Meat that has been cut and packaged in plastic wrap doesn’t age; it just gets OLD. It needs air to age and give up some of the moisture. I’ve noticed that some up-scale supermarkets have aging boxes in the meat department. The meat is pricey, but if you can find genuine properly aged beef, it might be worth the splurge.

Great information…This is just the support your customers need for our ThermoPens and Smokes….Thanks so much

Excellent treatise on how to buy, cook and enjoy a great steak dinner. The reverse sear is the best way to cook a good steak followed by sous vide.

What about aging and the difference between dry or wet aging?

Jim,

That is a fine point that needs to be made! Wet aging is aging “in the bag,” where the meat is left in a cryo-vac bag to age. Dry aging is done in a temperature and humidity controlled cooler.

In wet aging, the goal is tenderization via enzymatic action over time. As the meat sits in its protective bag, the natural enzymes in the meat slowly work to break apart proteins, making the meat more tender and flavorful.

In dry aging, a lot more happens. Yes, there is the enzymatic action, but there is also evaporation. When the meat loses water, the flavors of the steak are concentrated, which tastes better. Also, there is a literal element of rot in the dry aging process. The outermost pits of the meat actually putrify, but the byproducts of that process are delicious. The flavor process is similar to aging a block of cheese, with bacteria at work to create deeper flavors. But the rot is also the reason a dry-aged steak is so expensive: they cut all the rot off of it before they send it home with you, and that waste (as well as any water lost to evaporation) goes into your price-per-pound.

I hope that helps!

A well written article (a reference, really) with ALL the details! Hope to see more of these???

Thank you SO MUCH for this article!

I’ve always paid attention to the descriptions of beef sold at the supermarket while examining the marbling, but now I’ll actually have a better idea of what I’m purchasing and why.

Now, let’s put those Thermapens to work!

The information was simply fantastic. GREAT JOB!! I feel as though I learned a lot from reading it. I will be sure to save it.

I have had good luck with the reverse sear method, but after much trial and error prefer searing the steak first and then either putting it in the smoker at 200 – 225 degrees. I notice little difference in the texture but find it easier to control the final temperature than if I sear it after the low temp smoking.

I’m just totally impressed. Much was known, but MUCH was learned. Thank you for this; I’ll read it several times, I think; and am looking forward to my next steak dinner!

I have heard of folks ordering their steak “blue”. I assume this to be just shy of raw; could you shed some light to this?

Ron,

Blue is a term for very rare. It’s just past raw. Not my favorite way, but there’s no accounting for taste!

Great article. I’ve read bits and pieces of a lot of what you’ve covered here through the years.

However, you’ve put it all together for us and I thank you for that.

Well written article (thank you!) and thoughtful comments. I’m guessing a lot of folks didn’t know the difference between a NY and a KC strip. Despite what some say, I’m a bone-in guy . . .

Joel,

I’m glad you liked it! And hey, if you like the bone in, that’s just great! Happy cooking!

The best investment i have ever made.The mk4 is pricey but well worth the money.I use it for bread, sausage and steaks. Recently bought a second one for my daughter and future son in law. It is a must have for the outdoor griller. I did the reviews before purchasing,but if its good enough for the Americas Test Kitchen it was good enough for me.Keep up the blogs they are very helpful.

I tell my waiter I want my steak taken off the grill at 130*, I then hand him or her my ThermoPop, by the way, be sure to bring it back. lol

That’s FANTASTIC!

The letter grade indicating the age of the animal is not discussed on the USDA / FSIS web-site. Who assigns this letter grade and why?

If present how does it help in choosing product? I would assume that meat from a younger animal is preferable and this age does not relate to the “dry aging” that some restaurants cite.

Thanks for all the useful information about beef grades, cuts, and preparation tips (and for my just-purchased ThermoPop).

Quality grading is not mandatory, so some producers forego it. I also can’t find any info on who assigns the score, however. You are correct, though, that the age refers to the animal’s age, not the age of the beef as a cut itself.

This was a very informative article. I order my steaks, ” the rarest you can legally cook it”. At home I never cook my steaks over 117 degrees.

Can you tell me where short cut rump comes from

I had never heard of it until you asked! The only reference I can find to it point to it being a sirloin, but I’m not sure of that.

This is a marvelous tutorial on beef. My grandfather was in the wholesale live cattle business when I was a kid (80 years ago). In addition to knowing how to select meat, it’s just as important to know how to properly trim the meat to remove the sinew and silver-skin and other bits and pieces that will never get tender no matter how long they’re cooked. That’s where a good butcher comes into play. Their skill levels are highly variable. Some just mutilate the meat; others enhance it. Befriend your butcher!

Absolutely! A skilled butcher you can trust is one of the best food friends you can have.