Chicken Internal Temps: Everything You Need To Know

The number of dinners in America that include chicken is astonishing. From freezer meals to BBQ chicken to fried cutlets, from restaurant chefs to college-dorm cooks, chicken is truly one of America’s favorite meats.

And yet chicken is too often woefully overcooked. Fearful of contracting a food-borne illness from undercooked poultry, many Americans roast, fry, bake, or grill their chicken until it is dry, tough, and rubbery. Overcooked chicken doesn’t “taste like chicken” anymore, it tastes more like chalk.

Why is that? Read on to learn!

Cooked chicken temps: safety concerns

All poultry, chicken included, have Salmonella bacteria endemic to their bodies—meaning that every single chicken has some Salmonella in it. The truth is that the chance that there is Salmonella in the particular portion of raw chicken you are preparing to cook is extremely high.

Of course, you needn’t necessarily freak out about that, because Salmonella, just like other harmful bacteria, can easily be killed by cooking food to a high enough temperature.

The USDA publishes critical food safety temperatures for all foods, including chicken, that reflect the heat needed to kill the bacteria commonly associated with those foods. And most people know that the recommended safe internal temp for chicken is 165°F (74°C).

The mistake most people make is not bothering to check the actual temperature of their chicken! Instead, they rely on physical indicators of doneness from a pre-technological era. Many people will check their chicken’s doneness by checking to see if it is firm when pressed, if it is no longer pink inside, or if the juices run clear when the chicken is cut.

But those methods are seriously flawed! By the time chicken is “firm,” the proteins in the meat will have squeezed out much of their water, making the chicken dry. (As the proteins in the chicken breast denature and curl up, and, if they cook far enough, they squeeze out the water molecules that cling to them.) The color of meat is also a bad indicator of doneness because pinkness can be caused by non-temperature related factors, such as pH. As for cutting the meat to see how the juices run, I suppose it could be a good doneness indicator if you want to eat chicken that has had its juices literally drained out of it before it reaches your plate.

Below we’ll cover three thermal paths to getting better chicken.

Beginner solution: check the chicken temp

The first—and most basic—solution to under- or over-cooked chicken is to use a thermometer when you cook your chicken! (A Thermapen® is ideal for this task, as you’ll see shortly.) Yes, your grandmother checked it with her thumb, but she learned to cook before computers were invented! Now we have fast, accurate thermometers that can give us far more information about our meat’s doneness than a tactile push could.

To use a thermometer correctly in temping chicken, you’ll need a thermometer that is fast enough to show the differences in thermal gradients in the chicken.

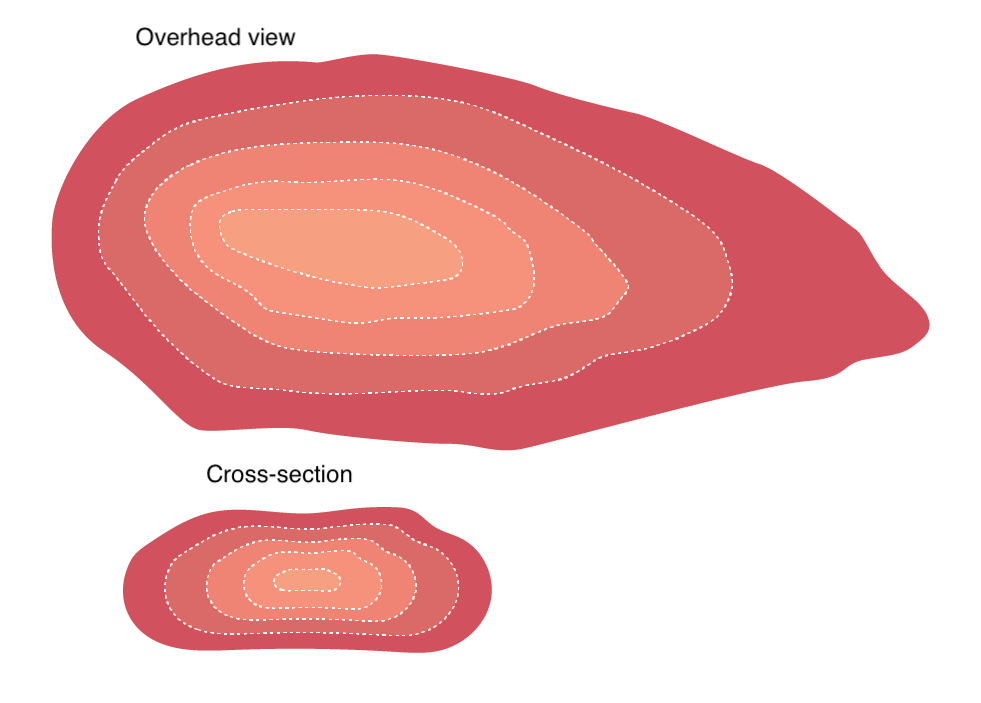

It goes without saying that a chicken breast cooks from the outside in. As the outermost layer of molecules heats up, they share their heat with the next layer, and those with the next, so on down to the coldest spot in the chicken breast, the thermal center. Those differences in temperature make up the thermal gradients.

To take the temperature of your chicken, push the tip of your thermometer’s probe through the thickest part of the meat and pull it slowly up through the meat. Watch the display for the lowest number that it reads: that is the doneness of your chicken. That’s why you need a fast thermometer, to read the gradients as you move the probe through the meat.

By checking actually using a thermometer you can nail your target temperature without going over. Better chicken is within reach…

Is 165°F really key? Bacterial death is dependent on temperature and time

Ok, so most people know about 165°F (74°C), but what most people don’t know is that food safety (bacterial die-off) is a function of both temperature and time. You can achieve the exact same bacterial death by holding your chicken at lower temperatures for longer times with the exact same assurance of safety.

The USDA provides guidelines for industry on food safety and uses pasteurization tables to indicate how long it takes to kill enough bacteria at a given temperature. Below you can see one such table for medium-lean chicken.

Chicken Safe Temperature Chart

| Temperature | Time to achieve bacterial death (in lean white meat) |

|---|---|

| 145°F (62.8°C) | 9.8 minutes |

| 146°F (63.3°C) | 7.9 minutes |

| 147°F (63.9°C) | 6.3 minutes |

| 148°F (64.4°C) | 5 minutes |

| 149°F (65°C) | 3.9 minutes |

| 150°F (65.6°C) | 3 minutes |

| 151°F (66.1°C) | 2.2 minutes |

| 152°F (66.7°C) | 1.7 minutes |

| 153°F (67.2°C) | 1.3 minutes |

| 154°F (67.8°C) | 1 minute |

| 155°F (68.3°C) | 49.5 seconds |

| 156°F (68.9°C) | 39.2 seconds |

| 157°F (69.4°C) | 31 seconds |

| 158°F (70°C) | 24.5 seconds |

| 159°F (70.6°C) | 19.4 seconds |

| 160°F (71.1°C) | 15.3 seconds |

| 161°F (71.7°C) | 12.1 seconds |

| 162°F (72.2°C) | 9.6 seconds |

(This chart is based on guidelines from the USDA for food manufacturers. You can read the whole article and get expanded charts in PDF version of the document below.)

Loading…

Loading…

Intermediate solution to dry chicken: cook to 157°F and HOLD it

If you want even better chicken than you get from temping your chicken to 165°F (74°C), use the pasteurization tables to pick a lower temperature to cook to, and hold your chicken at that temperature for the appropriate amount of time.

(Note: the pasteurization tables vary depending on the fat content of the meat, though they don’t differ much across the fat percentages. Breast meat is very lean, while thigh meat is much fattier. Use the tables accordingly.)

With this method, you would pick a temperature from the chart, verify that the chicken has reached that temperature as you we discussed above, and hold it at that temperature for the appropriate time interval. I really like 157°F (69.4°C) for my chicken, so I’d hold it at that temperature for 31 seconds.

You can use the min/max function on your ChefAlarm® to monitor the temperature and make sure it doesn’t dip during your holding time. In the above image, the min temp is 40°F. By pressing and holding the CLEAR button for a few seconds, the min/max will be reset to the current temperature. You can hist start on the timer and watch it for 31 seconds. You can then check the min temp to see if it dipped below 157°F (69.4°C).

Advanced thermal thinking: carryover cooking in chicken

If you’re concerned about holding it at 157°F (69.4°C) for 31 seconds, you certainly needn’t be: carryover cooking will make sure your meat is safe!

Most people don’t realize that when you take a chicken breast off of the heat, the residual heat in the outermost layers will cause the internal temp of chicken to keep rising, creating a temperature equilibrium in the whole piece.

This is advanced thermal thinking because it requires more judgment—it entails a dynamic target with two variables: the temperature of the cooking environment and the mass of the meat being cooked.

Meat cooked in a hotter environment will have more carryover because there will be more thermal energy in the outer layers that will be pumped into the center. Hotter cooking means more carryover cooking: chicken cooked in a smoker at 250°F (121°C) will have much less carryover than a spatchcocked chicken roasted at 425°F (218°C).

A large piece of chicken, say a whole bird, will have a lot more thermal mass that can move heat into the center, meaning the internal temperature for chicken will rise more than on a small piece. A breast experiences less carryover than a whole bird does, and a wing even less.

What that means for you is that you might set an even lower doneness temperature on your ChefAlarm when you roast a whole chicken than you would if you were just baking some breasts. As you get used to monitoring temperatures, you will gain a sense for how carryover works in various situations and be able to set your alarms better to get exactly the results you want.

Dark-meat chicken temps: 175°F (79.4°C)

Everything we’ve discussed up to this point is focused on cooking chicken breasts. Dark meat is a whole other kettle of fish. While dark meat does need to be cooked to a safe temperature, it must actually be cooked to a higher temperature to be enjoyable. Dark meat has much more connective tissue in it, and that tissue needs to be broken down to make it tender. If you don’t like dark meat because of its gummy, rubbery texture, then you aren’t cooking your dark meat hot enough! For the connective tissues to break down, dark meat must be cooked to at least 170°F (76.7°C), but it is even better if cooked to 175°F (79.4°C).

But won’t that dry the meat out, like in the breast? No. As the connective tissues break down, they actually release water into the meat, replacing the moisture lost in the initial protein-squeeze. In fact, chicken thighs can achieve a consistency much like pulled pork if cooked just right!

Recap: temp your chicken!

Most people overcook chicken because they use physical artifacts to cook it, instead of actually measuring its temperature. The only way to know how well your chicken is cooked is to use a thermometer, preferably one that is fast (so you know what’s happening now) and accurate (so you know you’re not being lied to by your thermometer).

Though the USDA names 165°F (74°C) as the doneness temperature for chicken, cooking it to a lower temperature and holding it at that temperature for an appropriate time will result in juicier, tastier chicken. Add to ensure safety when cooking to those lower temperatures, track your chicken’s carryover cooking.

By following these guidelines and using a Thermapen® and a leave-in probe thermometer to cook chicken, you’ll get meat that is safe, juicy, and tastes better than, well, chicken! Happy cooking!

And now that you know how chicken temperatures work, take a look at some of our other posts on chicken:

- Sheet pan chicken

- Baked chicken breast

- Delicious fried chicken

- BBQ chicken thighs

- Butterflied whole grilled chicken

- Simple roasted chicken

- Harry Soo’s Malaysian Chicken Satay (with a video featuring Harry himself!)

- Whole, smoke-roasted chicken, cooked hanging in a pit barrel

And if you want to know more about the difference between the ChefAlarm and the Thermapen, you can read up on which thermometer to use.

Shop now for products used in this post:

Can you use a ThermoPop to check the temperature of chicken on the grill?

Debby,

Absolutely!

Now I’m confused. How can you cook a whole chicken using 2 different temperature guidelines. If you pull your bird with the breast temp at 157 degrees, even with carryover cooking the thighs will not reach 175. And if they did, your breast would be way overdone according to your 157 target.

David,

Cooking a whole bird is a true puzzle, in that regard. How does one get tender dark meat but juicy white meat? I recommend taking a look at our guidelines for cooking a whole turkey, which has the exact same problem. Take a read here.

You might try spatchcocking your bird.

In my experience this method results in both dark and white meats get to their respective temps at the same time.

pork need to be at 200 for fibers to break down and make that bone pull out, why is dark chicken temp 175 for that to happen and not 200?

Also, if I read the chart it seems 157 for 31 seconds is a no brainer for better chicken, but if you were going to go 165 temp it would take more than 31 seconds to get from 157 to 165, so basically once your chicken hits 157, by the time you get a plate and remove from grill, and the chicken would get hotter before cooling, IE residual temp increase considered, its reallly done at 157 degrees …..make sence? would you agree?

Jt,

The connective tissues in chicken thighs are neither as tough nor as prevalent as those found in tough mammalian muscles like brisket or ribs. Cooking to 175°F does a great job of making them tender and delicious.

As for your second question, I think I’ve answered it in my response to Jim’s query. If not, please feel free to contact me.

Great info…but to be clear can you define “carry over cooking?” Would be pulling the chicken from the heat source (resting) for 31 seconds and letting the chicken breast come up to 165 degrees ? Thank You, all the info is really good food for thought (pun intended) ?

Jim,

Carryover cooking is when the temperature in the thermal center rises after being removed from heat. It will not always necessarily get you to 165°F. If you have a chicken breast and cook it to 157°F, it might get up to 165°F during carryover cooking (if you cooked it over VERY high heat), but it probably won’t. The 31 seconds makes it safe even if it only stays at 157°F the whole time.

In sous vide cooking, for instance, your meat may reach the target temperature and neve move another degree higher. There is no carryover cooking, but you’d want to hold it at the target temperature for the appropriate time.

Carryover is something to be aware of so you don’t overcook and dry out your meat.

thanks for such an educating article that also helps me figure out how to use my thermometer !

Great article! The time/temperature ratio is a great tool. This information should be included with every grilling appliance sold at the big box stores. It may save someone from a lifetime of bad chicken…

Fantastic and informative article, as always! Just one question .. how exactly are you “holding” the chicken at 157 degrees? Thanks!!

Diane,

Great question. Really, we mean that you just need to make sure the temperature doesn’t drop in the center, but to keep that from happening, it’s a good idea to cover the meat in foil during the pasteurization time. For longer rests (lower temps), placing the meat in a warm oven will keep the internal temp from dropping.

Thank you!

The report from USDA was dated in 1999. Is that the newest?

Patti,

The USDA wheels grind exceedingly slowly. Current research supports the information given here, but the USDA does not put out new or even updated regulations with any frequency.

I have read many, many cooking articles over the years but this is THE BEST one to explain the nuances of cooking chicken. Thanks, Thermoworks!

Hi, the temperature that you give was for the chicken meat. What if the temperature of chicken leg achieved 79.9C and above but the bones still have runny red bone marrow. Is still safe to eat or must be cooked until dark brown colour bone marrow?

Red marrow is still safe…if it has reached temperature! See our post on bloody-looking chicken.

I personally think your article is fascinating, interesting and amazing. I share some of your same beliefs on this topic. I like your writing style and will revisit your site.

Thank you for such an informative article.

I am a little confused about a couple of things, though.

First question: you make sure the temperature of the chicken remains no lower than 157 degrees for 31 seconds. Thirty-one seconds at 157 degrees corresponds to the table for meat that is 7 percent fat. Is that about the fat percentage of chicken breast?

Second question: another article on this web site recommends a pull temperature of 145 degrees for chicken. Is that simply the preference of that writer?

The article is here:

https://blog.thermoworks.com/chicken/thermal-tips-simple-roasted-chicken/

Thank you again.

Sources vary, but 7-9% fat for the breast is about right, so 31 seconds is close either way.

As for the other article, yes, that’s is a preference. The carryover in that recipe can dry things out, so pulling it at 145°F will get you up to a safe temp that won’t dry out.

Thank you for your insight.

Love it! Do you have pasteurization tables like this but for red meat?

Sadly, I do not!

Thank you. This is great information. My question is how would I hold my chicken at a certain temperature? If I wanted to cook chicken to 150 for three minutes, how would I do that?

Good question. In general, food temperatures will continue to rise for a while when removed from heat—carryover cooking. If you were to put a leave-in probe like ChefAlarm in your meat when it reaches 150°F, and reset the min/max function, you could set the built-in timer for 3 minutes and then look at the min/max. Chances are good that after 3 minutes the temperature will have gone up and then possibly back down a little, but won’t have dropped below 150. Covering the food with foil will help to hold more heat in, too.

150°F is pretty reliable for a whole chicken, but if you’re doing a thin cutlet, which cools much more quickly, go with a higher temp, 157°, for instance.

When you say “hold” the chicken at the temp does it mean the temp cant climb? Because from the chart it looks like if i start a timet for 1 min when the chicken hits 154F then im good just so long as the chicken doesnt drop in temp. Right?

Yes, the point is to make wure the temp doesn’t go BELOW. Depending on the cut and temp, you can usually either just let it sit, or maybe cover it with some foil. Temp rising is just fine.

Great article! Chicken has always been a challenge because it does come out overcooked if you wait til the center reaches 165. But I was always a little nervous taking it off early.

I have a slow cooker with a temperature probe. So if I cook chicken on low in the slow cooker, can I assume that reaching 160 and leaving it in there just a little longer is safe? (The slow cooker is “holding” the temperature?

Absolutely.

I just bought a dehydrator with the intention of preparing dehydrated chicken strips (sliced to about 1/4 inch width) as a treat for my pets. I can set my dehydrator at 165 degrees (I checked with an oven thermometer to ensure the machine reaches and holds that temp.) I’ve found conflicting information online about whether the chicken needs to be cooked before dehydrating. Since it will be heated to 165 degrees during the dehydration process (which takes from 4 to 5 hours), do I need to cook the chicken before placing it in the dehydrator or is it safe to use raw strips?

That sounds safe to me, especially for pets.

I used my new sous vide unit to cook chicken breasts. Based on the tables on this site, I wanted to cook the breasts at the lowest temperature that would assure safety.

The parameters I chose were 145°F (62.8°C) for the the sous vide bath. The bath came up to set temperature as expected. The breast that I was cooking weighed ~ 100 grams.

The procedure that I used was to then place the bagged breast into the bath and allow the chicken to come to the bath temperature of 145°F (62.8°C).

From the table, the “holding time” should have then been 9:54 after achieving the sous vide bath temperature, The chicken never reached the bath temperature of 145°F (62.8°C). It only made it to 58°C.

Should I have set the sous vide bath temperature higher than the desired internal temperature of the chicken?

Yes, and this is something most people don’t realize. Always set your sous vide to a temperature about 5°F higher than your target doneness to account for the asymptotic rise in temperature towards the end of cooking.

Thank you for this article and the fact you’re still responding to questions. I grilled chicken last night and watched the temp. I waited till it reached 165 before pulling. Today, I recalled that there are time vs temp considerations and found your article in my search. Referring to chicken breasts and considering the outer “layers” of the breast will be higher than 165F when the center is somewhat cooler, is there a temperature you recommend to not let any part of the breast get hotter than? I know grill temperatures are subjective and built-in grill thermometers aren’t the most accurate, but is there an indicated temperature that you recommend to keep the grill at that is a good compromise between cooking time and overall breast temperature?

The only way to keep ANY of the breast form overcooking is to cook it in an immersion circulator (sous vide). But a lower, slower temperature will get you more evenly-cooked meat with less extreme temperature gradients. 325°F is not a bad way to go. Any lower and the skin gets more rubbery.

As a physician with an undergraduate degree in microbiology, and a penchant for cooking, I have always been fascinated by the discussion of the need for meat to be cooked to a certain temperature to be safe to eat.

Yes, it is true that time and temperature will kill bacteria. It is also true, that the interior of a solid piece of meat is essentially sterile and that bacterial contamination of as solid piece of meat is limited to the surface. If you do not cut the flesh (or cavity) or poke holes into the center of the meat. bacteria and contaminants will be confined to the surface and perhaps a few millimeters of depth.

Having lived in Japan for several years, I have eaten plenty of raw chicken sashimi. I was horrified at first until I realized that is it only the surface that is potentially contaminated. Chicken sashimi is dipped into boiling water for a few seconds to thermally kill surface bacteria. The interior is raw and perfectly safe to eat.

Ground meat is another issue. That mixes the potentially contaminated surface into the center. Anything ground or significantly “slashed” (tandoori chicken) needs to be cooked to make sure that the interior is at appropriate temperatures for the appropriate time.

Here is something I’m wondering about. Say i check my deliciously seasoned chicken breast and it’s at 154F. I wait a minute and check it again and it reads 157F. It has technically been at temp (154F) and time (1min) to make it sufficiently safe to eat.

It feels like due to the nature of time required to heat the meat, there is a point somewhere in the 150s where it has been at sufficient time and temp to kill any devious little bugs. Would you agree with this?

Yes, I would. What we’re ultimately looking for is area under a temperature curve. As the temperature continues to climb, that area increases more rapidly than if the temperature was held constant. There’s a lot of nuance there, to be sure, and it seems like you get it, which will net you more juicy (and safe) chicken!