A Day in the Test Kitchen

Due to our sponsorship of the PBS documentary, “Fannie’s Last Supper,” I was recently invited to dinner at the home of Christopher Kimball, the celebrated editor of Cook’s Illustrated and host of America’s Test Kitchen. My wife, Suzette, and I have long been devoted readers of Mr. Kimball’s editorials and columns and his advertising-free, scientific method approach to testing recipes, cooking techniques and equipment. And apparently, an invitation to Mr. Kimball’s fully restored Victorian brownstone in Boston’s South End is something of a rare and coveted commodity, so we were up for it.

Our day began with a trip to the Test Kitchen itself in Brookline—part kitchen laboratory and part major television studio—where the “America’s Test Kitchen” programs are taped and produced. A beehive of activity, the Test Kitchen boasts more than a hundred employees, each of whom enters through the most unobtrusive side street door.

The day we were there, a formal tasting of various peanut butters was on the docket with more than a dozen ATK Culinary Experts meticulously annotating their opinions on several unlabeled samples. We overheard a discussion of a pending test of kitchen shears.

And Suzette got to take part in a crepe tasting.

I was amazed that every work space looked just like the television show with ingredients in little glass bowls and charismatic chefs of every possible demographic type working their way through minute variations of the same recipes. Our anticipation kept building throughout the day as employee after employee told us how jealous they were that we had a ticket to Chris’s home for dinner.

Later that evening we took a taxi to Mr. Kimball’s home and were escorted to the formal dining room, set for twelve. Suzette and I were joined by another couple representing a different sponsor, Mr. Kimball’s assistant and her husband, his literary agent, a PBS representative, Mr. Kimball’s wife, the illustrious

The first course was Mock Turtle Soup with what Chris described as a “secret ingredient,” and only later identified as fried brain balls. The soup required the boiling of an entire calf’s head along with the hooves and tail, but only through trial and error did the ATK chefs learn that you had to remove the brain first to get a proper result. The brain became the balls in the soup. These were tasty but paled in comparison to the “mock turtle” broth itself which was exquisite.

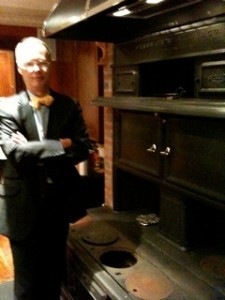

After dinner we were treated to a tour of the spectacular estate, complete with a wood-burning stove in the ground floor kitchen where our food was prepared.

It was an evening I will long remember.