Meat Cooking Basics 101: When to Cook Hot and Fast

As everyone who has learned to cook can attest, there are things that expert or professional cooks do and understand that don’t come intuitively. That’s fair. Cooking, like any other art, has deep, root-like traditions that can make it seem obscure, almost occult. Why can we cook this piece of beef this way, but not that way? Why do we not use that cut for this recipe? Do I really have to stir my sauces counterclockwise? 1

In this piece, the first of a series, we hope to clear up some of that obscurity. We’ll work to explain what’s happening when we cook meat at high temperatures—hot and fast cooking, as opposed to low and slow. We’ll go over which cuts we cook this way and why we cook them like that, what the high-heat methods are, what we achieve by them, the thermal progress that happens during such a cook, and the tools needed for a hot and fast cook. Whether it’s roasting a turkey, grilling Fire Chicken, searing a steak, or deep-frying wings, people love the results that come from high, intense heat.

This isn’t just for novices, though! Everyone can make their cooking better by deepening their understanding of these processes and materials. Let’s get to it!

Cuts that respond well to hot and fast cooking

The first thing to look at is what cuts we cook this way, and why we do it.

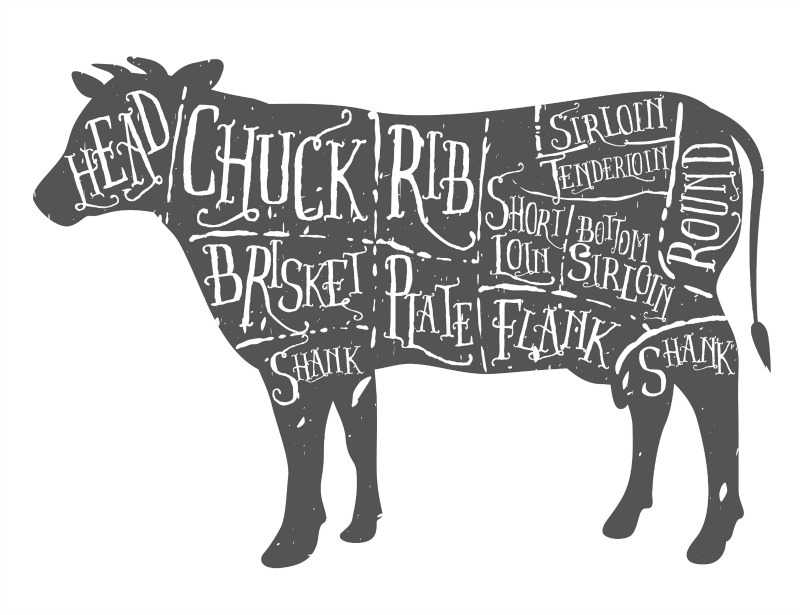

How we cook meat depends, for the most part, on where the meat is located on the animal. If a particular muscle is used frequently by the animal, there will be more connective tissue in it, and that connective tissue must be broken down to become palatable. We’re almost always cooking pieces of meat that are more tender—they don’t have all the collagen and other connective tissue that needs to melt.

For quadruped mammals, it happens that the higher up the animal you move, the more tender the meat becomes. Exceptions arise, but it’s a general fact that eating “high on the hog” (or the cow, or the elk) is eating more tender meat.

Make-up of fast-cooking cuts

Fast-cooking cuts have a low proportion of connective tissue, especially collagen. Collagen requires high internal temperatures to break down—over 175°F (79°C)— and render into gelatin. These cuts certainly have some of that tissue, but they have much less of it. They may be fatty or lean.

Things that respond well to hot-fast cooking include chicken breasts, pork loin, pork tenderloin, beef tenderloin, tri-tip, ribeye, and any steak-like cut. Most fish and many kinds of seafood also respond well to searing at high heat for short periods of time—tuna steak comes to mind. (There are low-slow fish! Octopus comes to mind.)

Notable exceptions here include any dark meat chicken, which is naturally chewier and more connective, but responds gloriously to high heat methods of cooking, as long as you cook them to a high enough temperature to pass the collagen melt temps. More exceptions can be observed where size makes up for collagen content. Flanken-cut pork ribs (Korean kalbi), and pork steaks, come to mind. Their extreme thinness allows them to reheat and render their connective proteins quickly enough that high-heat cooking makes sense.

Size of fast-cooking cuts

High-heat cooking is a small-foods game. A searing, screaming heat is great to sear a ribeye steak, but try to cook a whole prime rib at that kind of heat and you’ll ruin the whole thing. Yes, you should sear a prime rib at some point in the cooking, but you don’t just cook it full-bore the whole time! Smaller cuts allow for the temperature gradients (discussed below) to work in your favor, giving you optimal crustiness with tender insides. Larger cuts don’t play this game as well.

So, to sum up, high heat cooking is for cuts of meat that are naturally tender and are not too large. If your meat falls in that category, you’re going to be able to create or find a good high-heat recipe for it.

High-heat cooking methods

It is, perhaps, redundant to say ‘hot and fast’ cooking. It is folly to cook slowly at high temperatures—leave a chicken breast on a grill for a half hour and see if it’s any good! Regardless, cooking hot, and therefore fast, is always appealing. For the sake of taxonomy, we can delineate “high heat” cooking as any method that exposes food to temperatures at or above 325°F (163°C). This means baking, broiling, deep-frying, grilling, sauteeing, pan-searing, griddling, and roasting. All of these methods are excellent for the kinds of cuts we’ll describe below, and they all produce the characteristics we seek when we cook hot (and fast).

What do we achieve by cooking hot and fast?

The tender pieces of meat that we cook in this way have less connective tissue and that means they don’t need to cook as much to become palatable. And that plays right into what we’re looking for with a hot/fast cook, namely lower internal temperatures in tandem with Maillard browning.

Lower internal temperatures for tender cuts of meat

I’m going to go ahead and call the pieces of meat that are lower in connective tissue and can be cooked in a solely hot-and-fast manner “steak-like.” Now, I know that a chicken breast—or a trout filet—is not comparable to a steak, but we cut steaks from the parts of the cow that have less connective tissue, so it does fit in its own way.

Steak-like cuts, in general, perform excellently when cooked to lower internal temperatures. Not only does their natural tenderness get to shine through, but their lack of collagen reserves means that they can dry out once their proteins start to tighten up, so cooking them to higher temps is … bad. Chicken breast cooked past about 155°F (68°C), for instance, starts to dry out quickly. The same goes for a seared duck breast or a filet steak. (We don’t think twice about serving a steak or a duck breast at 132°F (56°C) because of this—tender juiciness is of utmost importance! Chicken breast … we risk a little dryness in the service of food safety.)

Maillard browning

If we want these cuts cooked to a lower internal temp, it seems counterintuitive to cook them at higher temperatures. You can certainly cook them slowly at lower temps to get where we want to go, but tenderness is only half the game! Cooking quickly allows us to give meats some delicious Maillard browning, making them far tastier.

Maillard browning is a reaction that is similar to, but distinct from, caramelization. Where caramelization is a reaction that sugar performs itself, Maillard browning involves sugars—whether free (simple) or as part of starches—and proteins. The reactions involve their combinations and reductions and are exceptionally complex. They’re hard to work out, chemically, but they produce wonderful flavor. The deep, rich flavors of seared meats (as well as the toasty flavors of bread crust and, well, toast) come from Maillard reactions.

And Maillard reactions are part of the reason that we cook meat at high temperatures. As Kenji explains it:

Although Maillard reactions can occur at relatively low temperatures, they are glacially slow until your food reaches around 350°F [177°C]. That’s why boiled foods, which have an upper limit of 212°F [100°C] (determined by the boiling point of water), will never brown. With high-temperature searing, frying, or roasting, however, browning is abundant […] To this day, the exact set of reactions that occurs when Maillard browning takes place has not been fully mapped out or understood. What we do understand is this: it’s darn delicious. Not only does it increase the savoriness of foods, but it also adds complexity and a depth of flavor not present in raw foods or foods cooked at too low a temperature.

-J. Kenji López-Alt, The Food Lab, Pg. 292

There’s just no way to get the flavor of a well-seared steak without searing it well! You can impart all the pepper and thyme you want to a pork chop being cooked slowly and gently, but you’ll never get that crisped-pork flavor. Maillard browning is one of the key reasons we cook hot and fast.

Carryover: what happens when we cook hot and fast

So, now we know what we cook this way and we know why we cook it this way. But what is happening in the course of the cook, thermally speaking?

From a thermal perspective, cooking hot and fast is the equivalent of a high-speed chase. You put a 40°F (4°C) chicken breast on a cast-iron skillet that is 500°F (260°C) and heat immediately starts flowing into the breast’s surface. The first thing that happens is the surface water molecules get excited, eventually boiling away and exposing the proteins directly to the heat. The proteins are also heating during this time, of course, but surface water acts as a surprisingly good insulator for the meat—that’s why you often read that you should pat your meat dry before cooking.

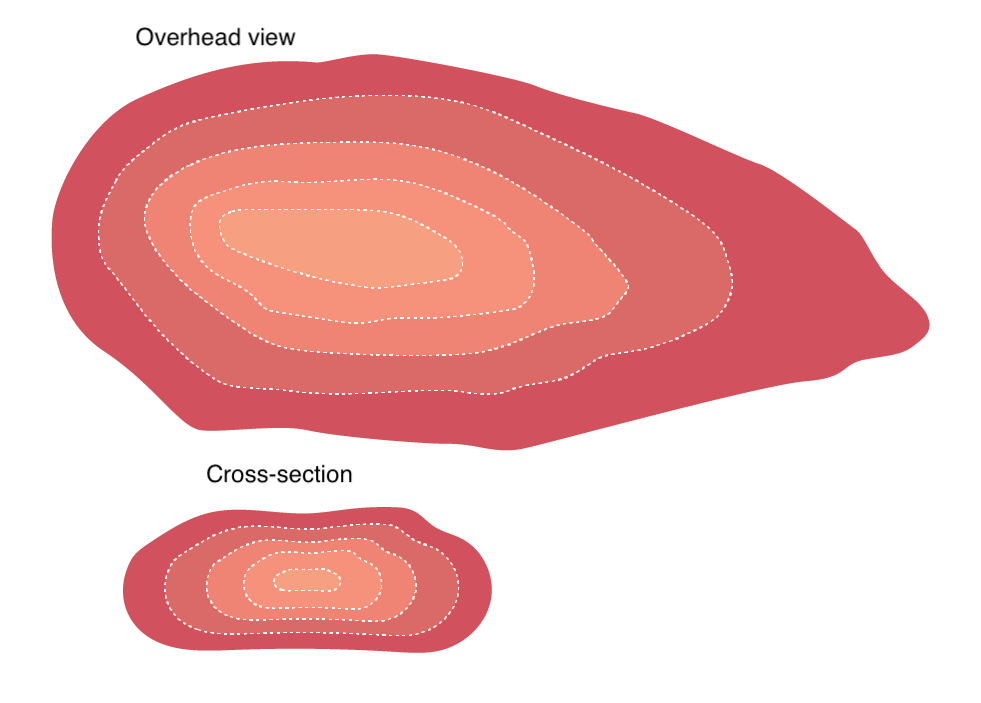

As the pan continues to pump heat into the surface of the chicken, the surface of the meat may be over 350°F, but just below the surface it may be only 120°F.2 A millimeter or two deeper in, it could be 20°F cooler still. This is the chase: all the internal temperatures will be running to catch up with the external temperatures.

This variation in temperatures as we move from edge to center is called a heat gradient. The hotter the pan—or grill or oven or broiler or hot oil—the steeper these gradients will be.

The molecules in any system (piece of meat) all want to share the same temperature, so when you finally take your chicken out of the skillet, the heat that is concentrated in the surface will naturally flow to the center of the meat, raising the internal temperature.

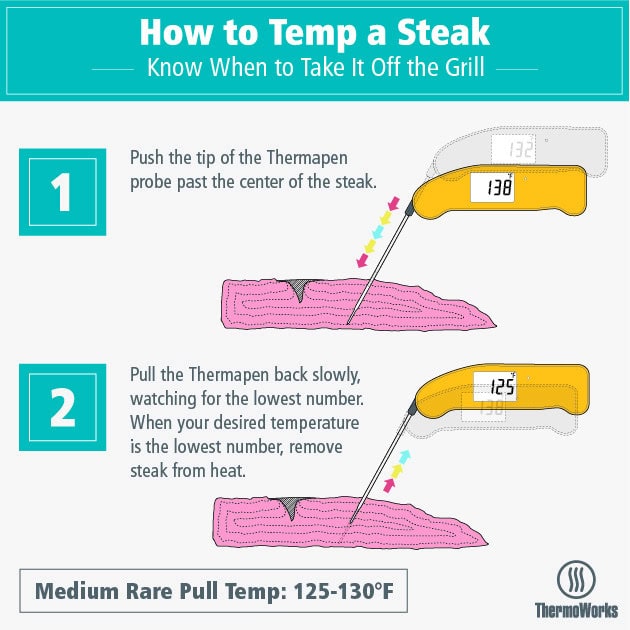

This, of course, is called carryover cooking, and it is something that must be taken seriously in high-heat cooking. The greater the external heat, the more carryover cooking there will be. This is why we often refer to pull temperatures as being distinct from final temperatures. I will pull a chicken breast well below food-safe temperatures if it has been cooking at a high temperature because I know that the temperature will continue to climb. And to get that information right, I need a tool.

Thermometers for hot and fast cooking

The best, the only, way to know how your food is progressing is to use a thermometer. For hot and fast cooks like we’ve been talking about, the best thermometer is a lightning-fast instant-read thermometer like Thermapen® ONE. Thermapen gives you up-to-the-second temperature information and it does it super accurately. Use your Thermapen to read the temperature gradients in your food by inserting it almost all the way through the meat and pulling it up through, reading the changing temperature off the screen. The lowest temp you see will be found in the thermal center of the meat, and that is the reading you’re looking for when determining doneness. Meat is only as done as its least-done part!

Whether grilling, pan-searing, roasting, or broiling, an instant-read thermometer is the best tool for the job.

Deep-frying is another matter. You can—I often do—use your Thermapen as a deep-fry thermometer. (Do not hang it from the edge of the pot where the flame will melt it!) Stir the oil, check the temp—great. But if you want a more constant monitor for the oil temp, reach for ChefAlarm®. ChefAlarm is a stellar deep-fry thermometer due to its high- and low-temp alarms that help you keep your oil within a specific temperature window. But even with ChefAlarm as your oil thermometer, it’s still best to have an instant-read like Thermapen for spot-checking the food. You can verify that each wing is done to perfection before removing them from the pot.

Those are the basics of why and how we cook at high temperatures. We want natural tenderness; we want Maillard browning. We can get both with smaller cuts that are low in connective tissue if we are aware of how thermal energy acts in the meat, moving from the outside to the inside in carryover cooking. And with the right tools, like Thermapen ONE, to actually keep track of the temperature, we can take control of the cook and get amazing results every time. Give something new a try this weekend, and happy cooking!

Shop now for products used in this post: