Annotating Cookbooks: a scientific approach to gastronomy

You’ve been waiting for days, maybe even weeks. Every day you go and check: nothing. But not today! It’s finally here! You can hardly stand the excitement as you rush back to the house from the mailbox and tear into it….your new cookbook! Ah, how often I’ve danced this waltz of purchase, anticipation, and reward.

Now the cookbook is here, and you can’t wait to dive in. You try one recipe, and it’s a home run, but when you make it again, it strikes out. Somehow the magic dried up between cooks. The cookbook has failed you.

Cookbook problems

There is a problem inherent in cookbooks, and it is not really their fault. Many cookbooks assume you don’t know anything about thermometry, because many authors probably don’t know much about thermometry.

Though more and more authors are using quality thermometers like the Thermapen®, they might assume that you, the humble, home consumer, don’t have a professional-level tool like that at your disposal. But you do! You can take control of your cooking with the thermal knowledge obtained from your ThermoWorks thermometer.

When a book—or the instruction card in your Blue Apron/HelloFresh meal kit—gives a recipe for a roast and says something like “cook 15 minutes per pound,” the well-intentioned author is making a wide array of wild assumptions about your oven, your refrigerator, your roast, and your preferences. Time-based instructions for many cooking procedures are useful only as the most skeletal of frameworks upon which to build your dinner. For real instructions you need real measurements. You need actual temperatures.

But just because you used your Thermapen to get that steak right one time doesn’t mean you’re going to remember how you liked it next time you cook.

Recording data to the rescue!

Science has the answer to this problem. And I’m not just talking about an explanation for the way muscle fibers react to heat. Science has a lot to teach us about the way we cook.

For instance, lab books. Every scientist performing an experiment has some form of lab book/notebook/data drive where they record their observations and work out their conclusions. And what is cooking a new recipe but an experiment of heat, chemistry, and taste in your own kitchen? We can certainly take a page from the scientists here.

Keeping a record of your data and observations in the kitchen can lead you to the Holy Grail of scientific experimentation: reproducibility. All scientists want to be able to create an experiment that can be recreated later or by other scientists, and cooks want to get a recipe to turn out right and then be able to reproduce that result later. So what can you do to get that kind of reproducibility?

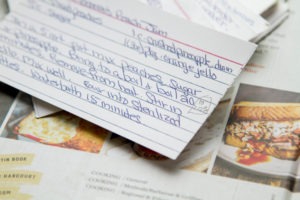

Annotate the books

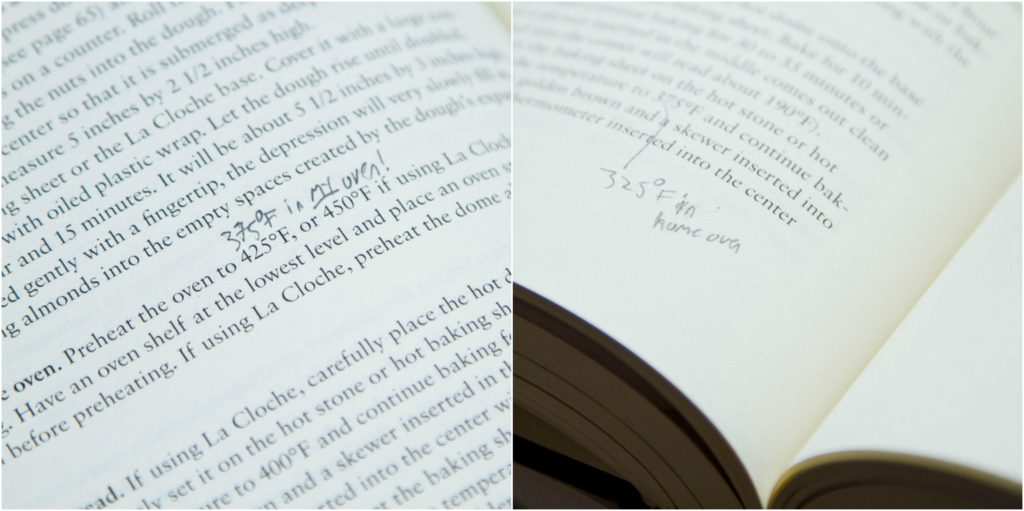

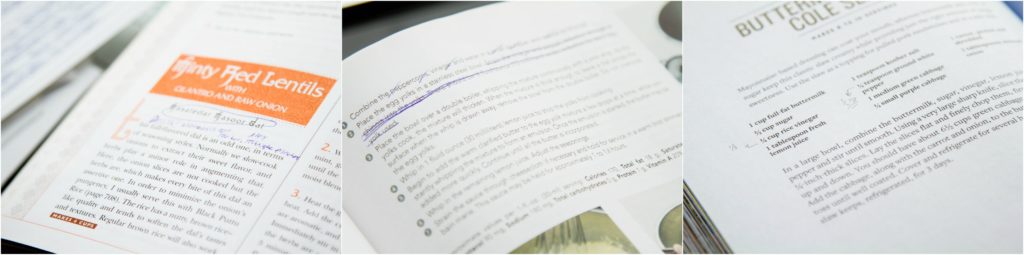

To ensure reproducible, quality results, add temperatures to your cookbooks. That’s right, grab a pen and just write them onto the recipe page. (You can start with our Chef Recommended Temperatures and a Thermapen to get your recipe headed in the right direction.) Monitor the temperature of your food throughout the cooking process, and record in the cookbook the final temperature you stop your cooking. After you eat your meal, make an assessment of how successful you were. What might you try differently next time? Write suggestions to yourself right on the recipe page, like “2° less next time” if you found it to be more done than you like, or “try searing first next time.” Over time, you will perfect recipes to your exact standards, and you’ll have the data to keep making it perfect.

If you use a ChefAlarm® or a Smoke® two-channel leave-in probe thermometer, you can also track the carryover cooking in your roasts by noting the highest temperature recorded in the “Max” temp field. The highest temperature achieved should be noted in the recipe as well as the pull temp. Write them both down next to the recipe

But, my books!

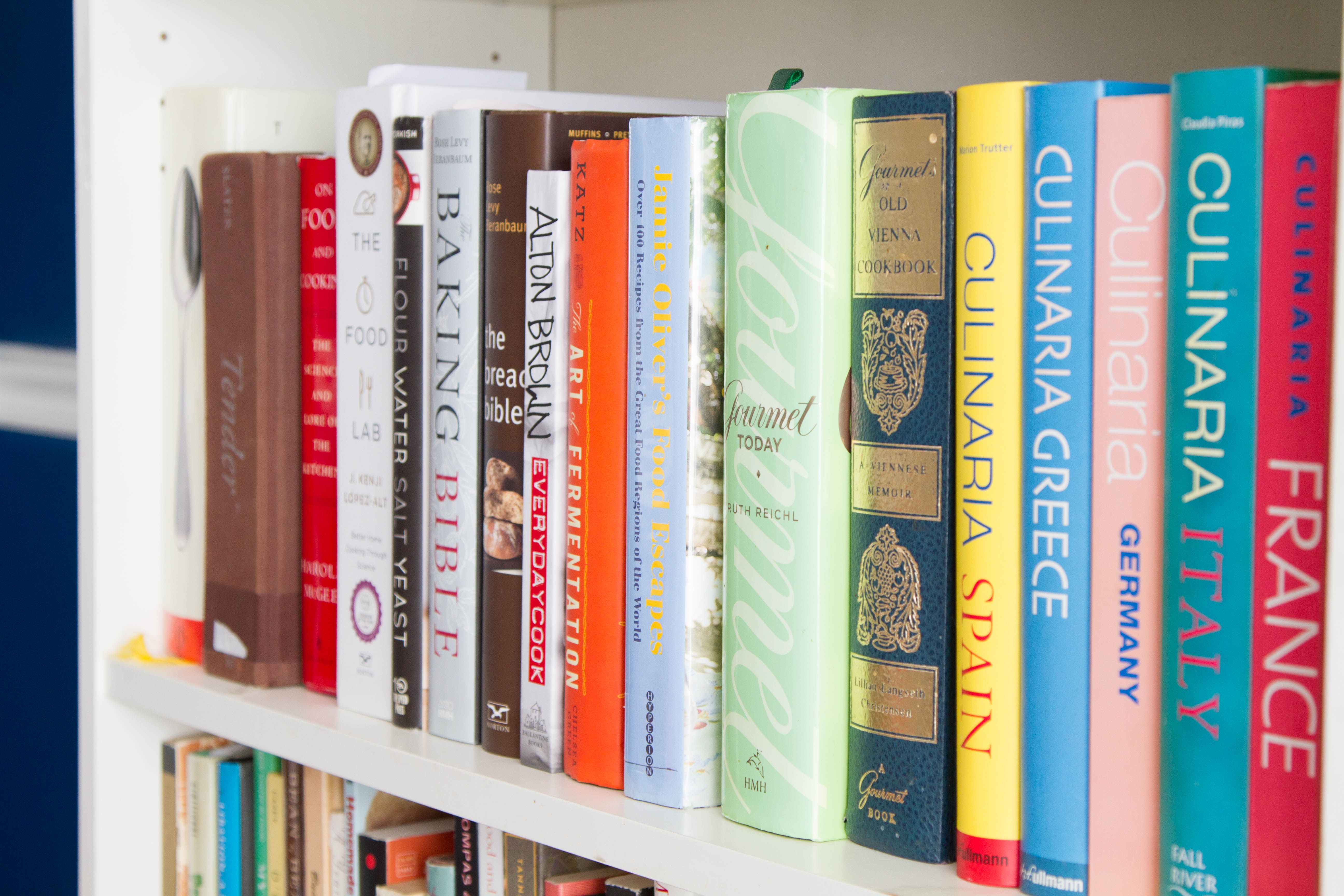

Don’t be afraid of marking up your precious books! Cookbooks are, according to one scholar at Michigan State University, among the most heavily annotated of modern books! My own books at home are scratched up with annotations on amounts of ginger and chilies to add, ideas for alternate applications, and notes on method. Anything that makes the recipe better for you, even beyond temperature, should be written down.

(As an aside, if you are really interested in exact and reproducible results, you should probably also change all of your volume measurements for dry ingredients to weight. Buy a good scale for cooking and never look back. It’s the best thing you can do for your cooking after getting a good thermometer.)

Family recipes

Not only can you improve the reproducibility of your cookbook results, you can also tackle that file box of family recipe cards. Those old family recipes bring back such nostalgia, but so often it’s the case that you try and fail to get it just right. Or you do get it right, but just one time, and then never again.

By annotating the recipe cards and tracking the temperatures, you can move toward perfection in incremental steps. Was the roast a little dry this time? Lower the pull temp a few degrees next time. Were the caramels too soft? Write it down and raise the boil temp by a degree next time. Then when you get to perfection, make sure the temp is written down for future generations. Your grandchildren will never have to say “these are good, but not as good as when Grandpa would make them.”

Conclusion

ThermoWorks thermometers are the perfect tools for getting things right in the kitchen, and if you treat them like the scientifically designed instruments that they are—taking data and recording it—you can turn your cookbooks into laboratory notebooks. Cooking with a thermometer gives you great results; recording how you do it gives you reproducible results. So get out those pens, both ink- and Therma-, and get to annotating!

This is a very nice article. I’ve never seen anyone write about this but I’m sure that many of us are doing this all the time. I just recently wrote to the NYT Cooking folks to ask if they would develop a feature that would allow users to annotate the recipes we save in their recipe box! Same point as you’re making here. Thanks!

If one makes several adjustments/notations, it might be a good idea to note the date of the adjustment. After 3 or more ‘changes’ on infrequently used recipes I was not sure which was the most current. So now I also date my notes! Hope this additional hint will help others.

Mary,

Great advice! Thank you for sharing!

Absolutely! I’ve been doing this for many years. I probably picked it up from my mother, and I suspect she developed that discipline as a research chemist during WWII. There’s always great info in this blog … I’m glad I discovered it last summer.

Ward,

We’re glad to have been discovered! Thanks for your comment and peek into your interesting family history!

I remember giving myself “permission” to write in my cookbooks, which went against everything I was taught as a child (do NOT write in your textbooks, young lady!). It was so freeing. Now, I use a combination of writing directly in the cookbook and on post-it notes. The post-its are for when I’ve not come to a conclusion that the alteration to the recipe was a good one.

If you don’t want to mark up your cookbooks use lined Post-Its and stick them to the recipe page or use an erasable pen like the Pilot Frixion line. I actually use the pens and the Post-It, that way I can have clean edits on my mark ups. The ink seems to stay erasable for quite a while (I have yet to have a problem but the older the ink the harder it is and eventually the paper will give away due to the eraser anyway). If you have highly tuned a recipe I always find it more useful to add it to my recipe manager or write out a clean copy so I don’t have to take the cookbook into the kitchen. No point in avoiding mark ups on it if I am going to splatter sauce on it anyway…

I have been doing this exact thing for years. Frankly my friends think I am being self critical when I talk about the food- ask questions like is “A” better? Or is “B” better ?

I make 2 cakes instead of 1 to compare the differences when I tweak recipes.

I keep running notes on a recipe over time until I get the recipe the way I want it.

I take other people’s recipes as a base then “fix” them by weight or at a minimum by cups, etc.

I hate recipes that state -1 sweet potato or 1 head of cabbage – 1 small onion. I change all the recipes I cook.

I make comparison sheets of different recipes in columns.

Now I am baking gluten free which is like a free for all – most “authors” know nothing about food science or cooking techniques. But at least all the experimentation has made me a much better cook.

I own thermapens & it’s a joke that I have to check my food’s temperature.

Wonderful article. Many people, including myself, refuse to “deface” a book because that is what we were taught as young people. Mortimer Adler, The University of Chicago philosopher, taught the opposite. Ownership of a book allows one to personalize it.

Early on (I’m 75) I created a work around with my cookbook collection, spawned much by the fact that I was losing recipes in the collection. Within the covers of a large 3-ring binder with appropriate dividers I created a personal cookbook. I initially copied recipes by hand and later started using a copier. On those separate recipe sheets I made and continue to make comments and suggestions and each dish, in my estimation, is improved because of it. Furthermore, as I gain a greater understanding of nutrition I am able to modify recipes to increase their health benefits.

I’m often called upon to cook when visiting family and friends. It is easy to take the book along and use it for inspiration as needed.

Pete,

Wonderful idea! Thanks for sharing!

I do a similar thing, but retype all recipes changing weights and adding temperatures and, once I have them as I want them, I laminate them to add to my folder.

If you just can’t bear to write in your cookbooks do what I do. Stick a post it note on the page. Then, because I have a tiny kitchen and prefer to put the recipe I’m currently using on a clipboard hung out of the way but still accessible from a pretty hook on a cabinet door, use a recipe program to write up and print out recipes that are “tried and true”. In that format future annotations are easy to jot down in real time and edit later.

What recipe saving file do you recommend?

Mary,

Unfortunately, I don’t have one I like. A good databasing program should do it, but I haven’t found anything I like. I rely on a clipboard, a notebook, and about 3 file folders to keep my recipes “organized.”

I’m with Mary, I want to know what program you recommend. I’ve tried so many I can’t count that high, and still can’t find exactly what I want. Until then, I’ll keep writing in my cookbooks. If you could maybe find a programmer, I’d chip in to pay for the work!

Chris,

If I could find one I liked, I would share the info with you! Does anyone have a recipe-saving program that they like? Comment!

I use “Living Cookbook” from Radium Technologies, Inc. It works pretty well and is fairly easy to use. You can create your own cookbooks and set up your chapters and subchapters in whatever manner works best for you and it’s easy to go back in and edit as often as you want to make changes.

Mary,

WEll, there’s a solution that sounds pretty good! Anyone else?

As a person who has lived all over the country, I can vouch that altitude annotations are important for reproducibility, and for meringue, humidity measurements are needed. Several ingredients in Grandma ‘s pound cake recipe will need to be heavily adjusted if she lived in Boston and you live in Denver. Oven temperature and cooking time will probably also vary between the two locations.

JT,

Excellent points! and if you cook in two locations, you could have both notes written in the recipe.