Best Temperatures for Making Jams and Jellies

Nothing beats fresh seasonal fruit, and making your own jams and jellies is a great way to capture fruit flavors at their peak. Naturally-occurring pectin is what causes sweet fruit spreads to thicken, and temperature is a critical factor in that molecular process. We have the key temps and tips you need to make the best batch of jam yet!

Making Jam: Using Pectin for Improved Flavor and Texture

Any concoction of fruit and sugar can be reduced to a sweet, thick, spreadable consistency, but often at the cost of an overcooked-tasting result. The addition of pectin will thicken the jam while maintaining fruit flavors that are fresh and bright.

Apples have particularly high amounts of pectin—especially in their skins, cores and seeds. Jams made with added pectin (either with added shredded green apples or commercial pectin) can be cooked in as little as 10 minutes, preserving their fresh flavor, color, and texture.

➤ Other Fruits High in Pectin:

Citrus rinds, crab apples, cranberries, currants, gooseberries, plums, grapes, and quinces.

Q: How exactly do I to cook with pectin, and how can I keep my jams from turning out runny?

A: The answer is in understanding the critical variables needed to properly set pectin: Sugar, acid, and temperature. Keep reading…

The Science of Pectin

This natural plant-based soluble fiber is what gives cell walls in plants their structure. When combined with water, pectin forms hydrocolloid* systems and gels. Pectin (either natural or in powder or liquid form) used to make jams and jellies requires the presence of sugar, acid, and the right temperature in order to arrive at its gelled state. When these factors fall into place, the pectin forms a web-like structure that holds the fruit and sugar in place evenly with the liquid. Your grandmother was a chemist and she didn’t even know it!

*Hydrocolloid: a water-based gel made up of evenly dispersed particles.

3 Factors in Manipulating Pectin’s Molecular Bonds:

Pectin is water-loving, or hydrophilic—it naturally wants to stick to water molecules. Getting the pectin molecules to stop bonding with the water and start bonding with itself to create a gel is where the factors of sugar, acid, and temperature come in.

1. Sugar

Sugar is very hydrophilic like pectin is. In the presence of sugar, water will bind to it rather than the pectin. Once the water is pulled away from the pectin molecules, the pectin is more likely to bind to itself. For this water transfer to occur, the sugar level needs to be above 60%.

2. Acid

Once the water bonds with sugar, their molecules are made up of mainly negatively charged ions. Acid increases the concentration of positive ions to neutralize the sweet mixture. Once neutralized, the pectin molecules begin to more fully bond to themselves, forming a 3-dimensional web where the rest of the juices are suspended together equally with the solids in the jam. The optimal level of acidity for pectin gelation is a pH of 5. Lemon juice or citric acid can be added to balance the pH as necessary.

Gelling begins to take shape with the addition of acid, but there’s one more variable to completely set the hydrocolloid structure of the jam—temperature.

3. Temperature: 217-222°F

Target Temperature Range:

Target Temperature Range:

Any jam or jelly must be heated to a rolling boil for enough water evaporation to occur, and reach the appropriate sugar concentration. This stage of the jam’s ratio of sugar to water is measured through temperature. The target temperature range of jams and jellies is 217-222°F (103-106°C)—the target temperature may vary slightly for each recipe.

Sugar Concentration:

In this high temperature range, enough water evaporation has taken place and the web of pectin becomes strong enough that it slows the movement of water to the point that it becomes a spreadable gel. A sugar concentration of 80% sugar/20% water.

☼ Sugar as a Preservative:

Sugar concentrations of 65% or higher prevent spoilage, withdrawing water from microorganisms, causing them to become incapacitated and unable to bring about food spoilage.

➤ Minimize Cooking Time:

Arriving at this stage quickly is best to retain the fruit’s best flavor, color, and the pectin’s thickening power (if cooked beyond this point the pectin will begin to break down, losing its gelling ability). You can speed evaporation to reduce cooking time by using a wide pan that will expose more of the jam’s surface area as it cooks.

Recommended Thermometers for Making Jam

● Instant-Read is Best

Instant-read digital thermometers such as the Thermapen are best for spot-checking the temperature of jam as it cooks. The jam becomes more viscous as it cooks, and the liquid will not circulate as freely while boiling as it did while at a thinner state. The jam’s uneven motion creates zones of different temperatures.

Relying on the reading of a leave-in probe alarm thermometer can be an inaccurate reflection of the mixture’s overall sugar concentration. A quick spot-check with a super-fast® digital thermometer will give a much more accurate reading if it is checked correctly.

How to Correctly Spot-Check the Temperature of Jams and Jellies

Hot and Cool Spots:

The jam’s uneven consistency and resulting hot and cooler zones can vary in temperature by as much as 10°F (5.5°C). This significant temperature difference could mean the difference between jam that thickens well and one that never seem to set up right if an inaccurate reading is captured. For an accurate reading, the jam’s temperature must be equalized first.

➤ How To Spot-Check Jam at a Glance:

- Use an instant-read digital thermometer

- Stir the jam well to equalize the temperature

- Place the probe in the center of the liquid and wave it slightly

- If necessary, tip the pot for an easier liquid depth for spot-checking

Q: I’ve been making my own jams for years, and the temperature never reaches the range of 216-222°F. What am I doing wrong?

A: You could be taking its temperature incorrectly (see above), or not adjusting for your location’s boiling point. Altitude is an important factor in the cooking temperatures for jams and jellies. Target temperatures will need to be adjusted depending on your location.

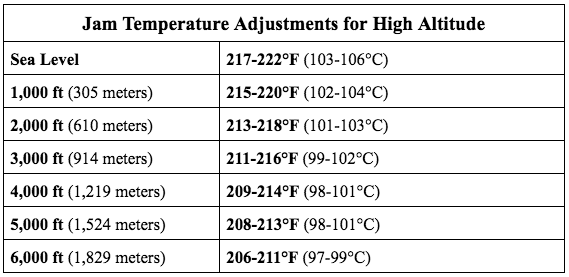

High Altitude and How it Affects Temperature When Making Jam

As elevation increases above sea level, air pressure decreases (for more information on high altitude cooking, read our post, High Altitude and Its Effect on Cooking). This lower air pressure causes water to boil at lower temperatures (boiling point is 212°F [100°C] at sea level), approximately 2°F (1°C) less for every 1,000 ft. increase in elevation. Sugar concentration increases more quickly when cooking at high altitude, decreasing the target temperatures for specific sugar cooking stages. See the table below for jam target temperatures at your altitude:

How to Adjust Your Jam’s Target Temperature Based on an Ice Bath Test and Boiling Point Test:

The most accurate way to find your ideal final cook temperature is with a boiling point test to see what the specific boiling point is at your altitude. Just a couple of degrees can make a big difference when cooking sugar.

➤ Temperature Reduction Factor

Subtract your boiling point from 212°F. This difference is your temperature reduction factor for altitude.

Example:

▪︎ Boiling Point at 4,500 ft: 203°F

212 – 203=9 Reduction Factor: 9°F

▪︎ Jam Target Temp: 220°F

220 – 9=211 Adjusted Target Temp: 211°F

☼ Fun Fact: What’s the Difference Between Jam, Jelly, and Marmalade?

They’re all sweet and spreadable, but what’s the difference?

Jam: Crushed or chopped fruit that is cooked with sugar, and sometimes added pectin, to a high enough temperature to yield a spreadable consistency. Jam contains pieces of fruit that are still solid, the mixture is not strained.

- Jelly: Fruit that has been crushed or chopped, cooked, then strained carefully through several layers of cheesecloth to remove all fruit pulp and seeds. The clear fruit juice is then cooked with sugar and pectin to a spreadable consistency.

- Marmalade: Made with citrus rinds, marmalade is both sweet and sour. Citrus rinds are naturally high amounts in pectin, greatly reducing the need to add any, and when cooked with sugar they become candy-like. Different types of citrus fruit can be used, and other fruits can be added for a different flavor profile.

More Tips for Success:

America’s Test Kitchen addresses several solutions to common issues when making your own jam in their book Foolproof Preserving, and these are just a few:

- Use the right temperature tool for the job. An instant-read digital thermometer like a ThermoPop is perfect for spot-checking.

- Use fresh fruit, not overripe. Fresh fruit contains higher levels of natural pectin.

- Measure all ingredients with precision. Using a digital scale is best.

- Do not reduce the amount of sugar. The final sugar concentration is critical for proper gelling. If a low sugar option is needed, use a reduced sugar recipe that has been developed to compensate for the lower sugar concentration.

Boil the jam, don’t just slowly simmer—but be careful not to overboil (track your temps!). Going beyond the recipe’s target temperature reduces the pectin’s gelling strength.

- Spot-check the jam’s temperature correctly. It makes a huge difference!

- Adjust the target temperature for your altitude.

- Use store-bought lemon juice. The pH level of freshly squeezed lemon juice varies too greatly.

- A pH level of 5 is ideal. (test with a Waterproof pH Meter [8680]).

Understanding the role of pectin and the key temperatures for success makes homemade jams and jellies foolproof! Whip up a batch today—your toast will thank you.

Products Recommended:

Resources:

Foolproof Preserving, America’s Test Kitchen

What’s the Difference Between Jam, Jelly, Compote, and Conserve?, SeriousEats.com

Keys to Good Cooking, Harold McGee

Target Temperature Range:

Target Temperature Range:

Jam: Crushed or chopped fruit that is cooked with sugar, and sometimes added pectin, to a high enough temperature to yield a spreadable consistency. Jam contains pieces of fruit that are still solid, the mixture is not strained.

Jam: Crushed or chopped fruit that is cooked with sugar, and sometimes added pectin, to a high enough temperature to yield a spreadable consistency. Jam contains pieces of fruit that are still solid, the mixture is not strained.

Thank you this really helped. I made strawberry jam, so now I am just waiting! Tastes great though. I appreciate the explanation of how the pectin and sugar need to be at the right temperature to ensure a good product. Thank You!

Author Stella Parks makes the provocative claim that pectin doesn’t provide material gelling power until it is heated to 220F. https://www.seriouseats.com/best-blueberry-pie-dessert-recipe

What do you think of this claim? Of course, I don’t know whether she’s talking about natural pectin, packaged pectin (regular or low-sugar).

Oh, this is interesting! The excellent Ms. Parks bases that claim on a reading from the book Mrs. Wheelbarrow’s Practical Pantry by Cathy Barrow, but a closer reading of some relevant passages in that book shows more nuance:

“Water boils at a lower temperature than 212°F at higher altitudes. The temperature at which preserves set, 220°F, will adjust downward as well.”

Barrow says what we say here. When it comes to preserves, water concentration, acid, and sugar are the key elements in activating pectin. Parks’ remark is regarding the internal temperature of pie filling, which will certainly not set at pie-baking temperatures—the setting of pie filling won’t be the same process as the setting of jam.

I think that Parks, while thinking of pie, simply misspoke about jam. Having cooked many preserves at higher elevations, I can say that pectic certainly does work at lower temps than 220°F. If it were strictly a measure of heat, not of concentration, then jams and jellies made where I live would be unbrearabley sweet and gloopy…more like fruit caramel.

I don’t know how to make my solution of fruit juice, sugar and pectin (from boiled apples). If I first add fruit juice to pectin juice and then add the sugar until I get the correct specific gravity. You say the sugar should be above 60% How do I measure that? Can you give the specific gravity. I can then work it out. Then I can correct the acidity and then boil away until I reach the correct temperature. With thanks

I’ve only worked one time with homemade pectin juice, so I can’t comment on that very well. Many jams have a final specific gravity of 1.33 or so, but that will vary with taste, etc. By the time you get up to the boiling temps we describe, the sugar content will be above 60% because of the way that sugar concentration works.

Hello. You mentioned in a previous article that marmalade has a different gel point than jams and jellies. But I did not see that temperature stated anywhere. I was hoping you could elaborate on that a bit.

Also, would one of your deep fry thermometers work for tracking the temperature of jams and jellies? Thanks for your advice.

Claire Ricci

When I wrote that, I had read that marmalades gel at a different point, but it looks like I may have been wrong. It seems they generally gel at 220°F! But yes, ChefAlarm, our best deep-fry thermometer, will work very well for jam and marmalade making.