Homemade Bread: Temperature Is Key

Bread—the staff of life, the very metaphor for food and companionship—is a subject shrouded in tradition, lore, and even legend. Baking bread is one of the most ancient practices of civilized society, and has, therefore, had plenty of time to allow some muddled facts to be folded into its production.

Instructions like “place on warm countertop” or, even worse, “thump bottom of bread to see if it is done” are commonplace in recipes for bread. But how can we cook bread differently now that we live in a technologically advanced civilization, rather than an Iron-age village? Thermometry, of course. And the thermometer you need for bread is a ChefAlarm® leave-in probe thermometer.

To discuss the finer points of thermometry in bread making, we’re going to take a look at lean-dough breads as our example. Lean-dough bread is the most basic kind, often composed only of flour, water, salt, and yeast. While the processes may vary from bread type to bread type within the class, they all share the commonality that they contain no fats (hence the name). Those with butter, oil, or other fats are called ‘rich-dough’ breads.

The thermal principles involved in bread making are essentially the same for rich- and lean-dough breads, with but one notable exception, and as the lean dough is ‘simpler,’ we will use one as the template for our discussion.

Bread Baking Basics

No matter the bread you’re making, there are three major stages: preparation and mixing, bulk fermentation and proofing, and baking. In each phase, there is a critical temperature element that can be accomplished more exactly with modern thermometry than with pre-industrial techniques. Our ancestors did a great job with what they had, but, as Nathan Myhrvold and the Modernist Bread team have shown, we can be more precise, and get more repeatable, exact results by discarding some of the lore and leaning on data. So with that in mind, let’s look at how temperature affects bread baking

Contents:

- Temperature in preparation/mixing

- Temperature in rising

- Temperature in baking

- Internal temperature for bread

- lean-dough Cuban bread recipe

Temperature and bread, and overview

Temperature in preparation/mixing

Though it may not seem like it, the temperature at which you mix your dough can have a significant effect on the outcome of your bread. The temperature at which your yeast blooms can affect the flavor of your bread. Yeast reactivates best between 110°F and 130°F (43°C and 54°C). But push the activation temp above 140°F (60°C) and you’ll kill the yeast before it can even wake up.

At the same time, if you use water below 105°F (41°C) to wake it up, the yeast will wake up grumpy and you’ll get off-flavors in your bread. You know how bad it is to take a cold shower in the morning when you wanted a hot one, and yeast feels the same!

Then there is flour temperature. Whole grain flours are best stored under refrigeration—or even in the freezer—to prevent rancidification. If you add freezing flour to your dough, it will take a long time to rise. Using room temperature flour eliminates this problem, but if you have cold four, you’re going to want to check its temp before adding it to anything. A great way to bring it to temp is to sift it from a foot or two above the countertop. As the individual grains fall through the sieve, they warm more quickly. Use a Thermapen® to make sure you’re not cold-shocking the yeast out of their comfort zone.

If you want perfect results, you will want to get your dough to an exact starting temp before fermenting/proofing it. Professional bakers, whose livelihoods depend on consistency, actually take into account their mixers’ friction factor when they work out their desired dough temperature (DDT). When kneading dough, the internal friction of the dough creates heat. Each mixer has a heat signature known as the ‘friction factor.’ Professional dough recipes take that number into account and have a final desired dough temp. In fact, there is a formula for the temperature of water to add given certain variables so that your dough comes out at the desired temperature.

To find the water temperature to add to your dough (not just ‘lukewarm water’!), Take the desired dough temp and multiply by 3. Then subtract the room temperature, the flour temperature, and your mixer’s friction factor. Whatever remains is the temperature of water you want to add to your dough.

3 X (DDT) – (room temp + flour temp + friction factor) = water temp*

(That formula works for Fahrenheit scale. See the bottom of the post for a note on Celsius.)

Again, a Thermapen mk4 will give you accurate readings for all of those temperatures, and truly repeatable results. Mind you, this is pretty advanced. Most consumer mixers don’t publish their friction factors, so you have to work the process backwards to find it empirically, and even if you do, most consumer recipes don’t have DDTs anyhow. But if you get serious, you will start using this.

(If you want an easy way to calculate your temperatures, check out the Desired Dough Temp calculator over at The Perfect Loaf. Play around with it, but you can get the equation above by entering ‘3’ for your mulitplication factor and ‘0’ for your preferment.)

Temperature in rising

“Place the dough in a warm spot in your kitchen” is one of my all-time least favorite cooking instructions. Warm in winter or warm in summer? How warm is too warm? Warm enough? Well, it turns out that science has answered that question. According to Harold McGee, the optimal temperature for fermenting and proofing bread dough is 85°F (29°C). Temperatures below that point take longer to ferment, and temperatures higher than that can produce unpleasant flavors in the dough.

Bakers overcome this problem with high-tech proof boxes that use complex algorithms to keep the temperature exactly right. Some home ovens have a ‘proof’ function on them that runs the oven in the neighborhood of 85°–90°F (29°–32°C). If you have one, more power to you.

If you don’t, I recommend the following solution: use an insulated cooler for your proofbox. Coolers will keep heat in just as well as they will keep it out, so you can maintain a relatively constant temperature over the hours needed to ferment your dough. Just measure out a gallon or so of water at 95°F (35°C) using your Thermapen to check the temp, pour it into the cooler, and either put something in the water for your dough bowl to sit on, or just float the bowl in the water. Close the lid, and let your yeast do its job! A ChefAlarm® probe can also be used to monitor the temperature of the proofbox, making sure that the temperature stays in the proper range.

To proof—the name for the final rise after shaping—your bread, try to set up a rack of some kind in the cooler that you can set a pan with the bread on.

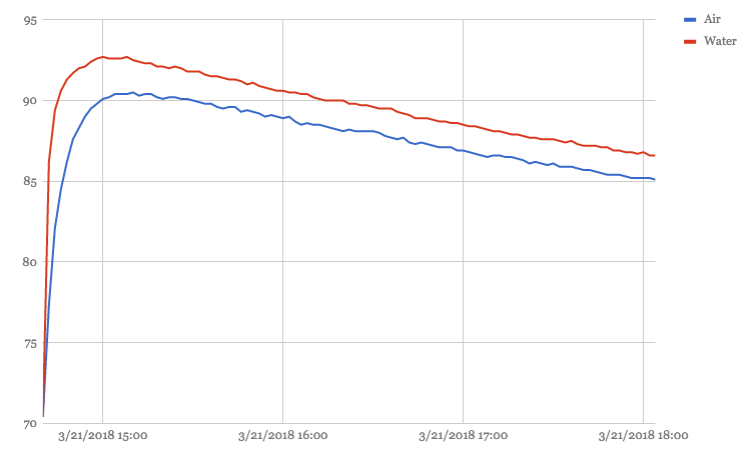

Why use water that is warmer than we want our proofer to be? Below is a graph of the temperature in such a cooler proofbox. Into a large cooler chest I put two gallons of 95°F (35°C) water. I put a probe in the water and used an air probe in the air and let the whole thing go overnight with the lid closed. I have included data up until the air temperature dropped below 85°F (29°C), which took about 3 hours. There was immediate heat loss to the walls of the cooler, and the air was never as warm as the water.

Temperature in baking

Once your bread is properly proofed, it’s time to bake. Oven temp is important, and you should follow your specific recipe for it, but most breads are cooked at rather high heat to create leavening steam inside the bread.

Though you needn’t measure the temperature of your bread at every point in the baking, it is an interesting thermal journey to see the ways that temperature affects the bread during baking. And to that end, I present the stages of bread baking:

The thermal stages of baking:

| 80°–170°F (27°–77°C) | Gasses are formed and trapped More CO2 from yeast is produced, as are gasses from any chemical leaveners and alcohol vapor from the fermentation |

| 140°–212°F (60°–100°C) | Starches gelatinize Starch granules swell and burst, creating a thick web of starch molecules |

| 160°–185°F (71°–85°C) | Proteins coagulate The gluten strands curl up, tightening their links with each other, and solidifying the bread’s structure |

| Across the temperature range | Fats melt In rich doughs, the fats that were emulsified in the dough melt, moistening the dough |

| 212°F (100°C) (adjusted for elevation) | Water boils Steam is one of the most important leaveners in bread |

| 320°F (160°C) and up | Sugars caramelize, Maillard reaction Sugars on the exterior will brown at this temperature and others will combine with proteins to produce nutty, toasty flavors and beautiful color |

| Carryover baking After the bread is removed from the oven, the temperatures will equalize, with the interior continuing to warm as the exterior begins to cool | |

| Staling (starch retrogradation) Once the bread reaches room temperature, the starch molecules start to shed water and to try to reassemble themselves in to starch granules, a process that makes soft bread feel hard and, well, stale |

(On Baking, Pearson, pg . 57)

To what temperature do I cook bread?

Those stages of baking are thermo-centric, but I’ve included them merely for your information—and because I think they’re pretty cool—because you can’t do anything about them. Proteins are going to coagulate at that temperature no matter if you use a thermometer or not. But where a thermometer does matter is for the doneness of your bread.

It has been handed down to us that a bread loaf is done when it produces a “hollow thump” when tapped on the bottom. Humbug. Most people don’t think about it, but there are varying temperatures for bread doneness, just like there are for beef (though an undercooked bun is less likely to cause illness than an undercooked burger). For lean-dough breads the recommended doneness is 190–210°F (88–99°C), while enriched-dough breads are done at 180–190°F (82–88°C) (S. Labensky, et. all, On Baking, 2nd edition, pg. 190). These critical temps are important if you want bread that is cooked through and not gummy in the center but is still moist and tasty.

To achieve these temps, you can spot-check—based on time—with a Thermapen, but a better idea is to monitor the internal temperature much like a roast. We recommend letting the bread cook for about 10 minutes—time enough for the bread to perform its oven-spring and to start setting up a bit—and then inserting a ChefAlarm, with the high-alarm set for your target temperature. The lean dough we’ll be making below was cooked to 200°F (93°C). As noted above, there will be some carryover cooking, so you should set your alarm a few degrees lower than your target temp, depending on the size of loaf.

And speaking of loaf size, it is a great reason to use a ChefAlarm in your baking. Resizing loaves from a recipe will mean a change in cooking time, but it will not mean a change in internal temperature requirements. If you make smaller loaves, use the ChefAlarm to make sure you don’t burn them. If you make a bigger loaf, rest assured it is not doughy in the middle by monitoring that internal temperature!

Lean-dough Cuban Bread Recipe

Florida’s famous Cuban bread is a close cousin of plain French and Italian breads. It is made traditionally with nothing but flour, water, salt, yeast, and a little sugar. Some recipes call for a small amount of fat (often lard) while some leave the fat out altogether, creating a lean dough that is intended for use the day it is baked.

We have based this lean-dough recipe on the Cuban bread recipe from King Arthur Flour, but have omitted the small amount of fat that their recipe calls for, and increased the quantities.

Ingredients

- 25 ½ oz All-purpose flour

- ¾ oz sugar

- 3 tsp salt

- 1+ Tbsp instant or dry active yeast

- 15 ounces water, 110°F (43°C)

Instructions

- Prepare a proof box by pouring 95°F (35°C) water into a cooler and closing the lid, or use your oven with a proof setting.

- (If using a cooler, monitor the temp with your ChefAlarm, with the low alarm set to 85°F [29°C])

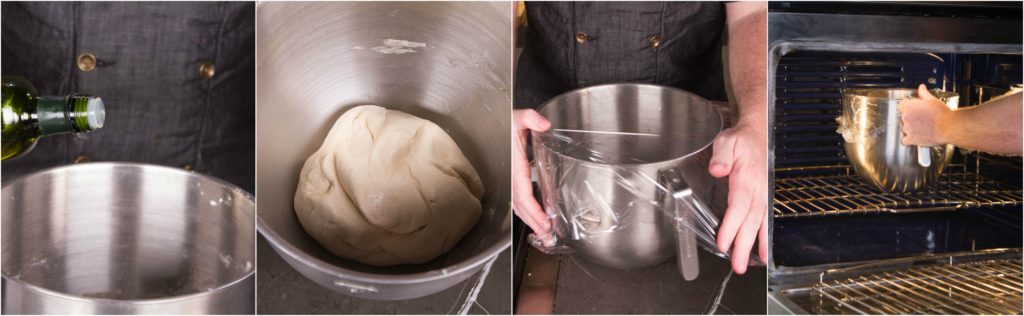

- Add all ingredients to a mixer with a paddle attachment.

- Mix on low speed until well combined.

- Scrape dough from paddle attachment and replace with dough hook.

- Knead for ~5–7 minutes or until a smooth, supple dough is formed.

- Remove the dough from the bowl and grease the bowl with a little butter or oil of your choice.

- Add dough back to the bowl and cover tightly with plastic wrap.

- Place the bowl with the dough in your proof box and let rise for one-half hour.

- Gently fold the dough over on itself to release some of the gas and stretch the gluten.

- Continue to let the dough rise until it has doubled in bulk, about another half hour.

- When the dough has risen enough, turn it out onto a floured surface.

- For loaves like we made, divide the dough in half and form each into a boule by gathering the dough into a seam on the bottom of the ball. You can make other shapes if you like.

- Place them on a baking sheet with either parchment paper or cornmeal on it.

- Cover the loaves and place back in the proofer for yet another hour. Halfway through, preheat the oven to 375°F (191°C).

- Uncover the loaves and spray lightly or brush with water. (If you want them to come out browner, use milk instead of water.)

- Slash the top of each with a sharp knife or razor blade.

- Bake the loaves for 10 minutes.

- Insert a ChefAlarm probe into the very center of the loaf and set the high-temp alarm to 200°F (93°C).

- Bake until the alarm sounds.

- Remove the loaves from the oven and let cool on a rack.

- If you want to thump the bottom of the loaf, do it, but only to make yourself feel happy, not because you have to live by the tyranny of cereal acoustics.

You will find that this bread has a close, tight crumb structure reminiscent of the appearance of store-bought white bread, but with a much more significant mouthfeel, presence, and flavor. Make a Cubano sandwich with it, toast it, or just eat the whole thing right now with butter. That’s what I did. And because you used your ChefAlarm, the texture is going to be perfect. So go make some bread and then break it with someone you care about.

*Desired Dough Temperature formula in Celsius

NOTE! for Celcius measurements, you have to take off a constant to make up for the two scales’ different freezing values. No matter the other factors, Celsius must also subtract 17.8 from the formula for correct outcomes:

3 X (DDT) – (room temp + flour temp + friction factor) – 17.8 = water temp

If you’re interesting baking bread, but want an amazing sandwich loaf instead of a rustic boule, check out our post about classic sandwich bread.

Products Used:

References:

King Arthur Flour, Cuban Sandwich Recipe

Harold McGee, On Food and Cooking

Labensky, Martel, Van Damme, On Baking

Martin,

Great information on the importance of temperature during bread making.

As a serious home cook and bread maker, I’d like to mention the importance of using a kitchen scale to weigh your bread ingredients. Preferably metric versus standard weights.

Consistency is achieved in bread making by being exact, as your entire article described. From my own experience, knowing optimal temperatures and exact weights of your ingredients give you the best recipe for consistent results.

Regards-

DS

Dan,

You are absolutely right! An accurate kitchen scale is every bit as important for quality baked goods as is an accurate thermometer. Every serious home baker should have one.

For example, when you call for 3 tsp of salt in your recipe, that can vary quite a bit. Is it kosher salt, fine sea salt, table salt? Please tell how many grams. And what is 1+ TBSP of yeast?

Mike,

You are right, mass measurements are far better than volumetric, and there is wide variation in salt densities. I used 3 tsp of Morton’s coarse kosher salt in this recipe. I don’t know off the top of my head how many grams that is. 1+ Tbsp is slightly more than a tablespoon, but if you were to use just 1 Tbsp it should be just fine, though it may take a little longer to rise fully.

What temperature do you bake a rich dough like brioche to

Mary,

Rich doughs like Brioche are cooked to 180–190°F (82–88°C), so slightly lower than lean dounghs.

This is why I always read your material: You have detailed, useful articles with professional advice about cooking. Sure you mention thermometers, but you never push them. Keep up the great work of being one of the most useful food resources out there! (Not to mention offering excellent products too.)

Not sure if this is wrong or right but I use my oven as the proof box. Have found by turning on the oven light it maintains a temperature of 90 to 95 degrees. I monitor it with my ChefAlarm with the air probe. If it gets to warm then I crack the oven door to maintain the 90 to 95 degrees. Also enjoyed the article as it contained some good info…..John

John,

A light in the oven is a great way to proof your bread, especially if you monitor it with a ChefAlarm!

Thanks John for that tip. Cheaper than a proofed. Sorry I jumped in on your conversation.

Confused about your recipe measurements. Are these in volume or mass? i.e. is 25.5 oz of AP flour, as listed in the recipe, equal to 722.9 grams?

For my cooking needs, all measurements use the metric system, thus no confusion as to ounces weight (mass) vs ounces liquid (volume).

As as suggestion, when publishing a recipe ingredient list, it would be beneficial to also list the needed ingredients in metric. This will better server the audience that is accustomed to the wider use of the metric system around the globe.

Jim,

Fair point! Yes, this was given as a measurement of weight with the equivalent 722.9 g. We will think hard about metric units for everything else. I myself use metric for bread baking at home, too!

Is it just my screen or is there no measurement for the all purpose flour ?

Scott,

Yes, it’s probably your screen. Mobile device? We’re working on that! it should read 25.5 oz of flour. Sorry for the inconvenience!

Is this the miracle of the loaves?

How does 1/2oz. flour yield all that bread?

Fred,

It sounds like you are reading the blog on a mobile device? I’m trying to fix the layout, but it is 25 1/2, not 1/2 ounces. Mobile layouts seem to remove the 25.

I live in the New Mexico mountains at an altitude of 7,000 ft. Is there an adjustment in the “done” temperature?

Tony,

An excellent question. For bread to be ‘done’ means that the proteins have coagulated enough to be rid of the doughy, raw texture, and enough gasses have expanded to create the crumb structure.

High altitude does not affect the temperature at which the proteins coagulate, so there is no problem there. And since we aren’t cooking the bread to an internal temperature at which steam is produced, we don’t need to worry about the steam forming the crumb inside the bread.

What will be interesting, perhaps, is that steam will form more easily in the outer depths of the bread, possibly creating a more open crumb structure around the edges than in the center. I’d be interested if this is the case!

All in all, I don’t think that the elevation will play a role in bread doneness. It can have effects on highly-leavened items such as souffle, or even an angel-food cake. But for bread doneness, no effect should be noticed.

These proofing/rising and baking temps are different than the temps you published on page 37 (thermotip: Bread) of the booklet that came with your thermometer. I’m going to use these new temps.

Jerry,

Good catch! I went back and compared what I wrote to the printed material, and I agree with your choice to go with what I have here on the blog! I did catch one thing though: I had published the fastest temp, 95°F, while the best temp for a balance of flavor and speed is 85°F. I have edited the blog accordingly. Happy baking!

Are there any “Keto” friendly bread recipes out there? If so, do the temperature profiles equally apply to those recipes?

Jon,

I know of no such recipe, as bread is a complex interplay of proteins and starches (carbs). However, if there were such a recipe, I am fairly certain the temperatures would remain the same. The same heat is needed for protein coagulation to occur and for the needed leavening gasses to form, so it shouldn’t change. Of course, the gelatinization of starches is going to be something that is less important, as starches are just complex carbs and you’ll be trying to leave those out as much as possible.

(once more, with proof reading)

My oven has a “proof” setting that I’ve measured as 100 degrees Fahrenheit, which is hotter than the yeast like, but will my big soggy mass of loaf get anywhere near that temperature in the time it takes to proof? I guess not, but it would be nice to have a reference curve or a rule of thumb or two regarding how fast how much comes to equal how hot an oven.

Thanks for any thoughts

Oliver,

Interesting question. The temperature curve will, of course, differ the deeper into the dough you get. The surface of the dough will get to 100° fairly quickly, while the center may not reach that temp by the time the proofing is done.

I don’t think I could come up with a reference curve because there are so many factors at play: mass and composition of dough, shape of proofing bowl, exact oven temp, and initial dough temp will all have an effect on the time/temp curve.

However, if you could use a ChefAlarm or other leave-in probe thermometer to monitor the internal temp of the dough, making sure that it doesn’t get too hot. You could also try running the proof setting for several minutes, turning it off, and then putting the dough in for it to proof. As the oven cools slightly, the dough will be warming into the optimal temperature.

I hope this helps, and I’m sorry I don’t have the differential equation skills necessary to provide you with the graph that, honestly, I’d love to see, also.

Happy baking!

Hello,

If I own a Dot instead of a ChefAlarm, is there anything I would be missing out on? In other words, would a Dot be just as effective in all of the steps listed above for the ChefAlarm?

Thanks,

Robert

Robert,

The DOT does not have all of the functionality of the ChefAlarm. However, depending on how you want to use it, that might be fine! The ChefAlarm has both a high and low alarm so you can be alerted if things reach a certain cooling point. It also has min/max functions that allow you to track peaks and troughs in your temperature curve and has a timer. But for bread baking, we’re mostly concerned with getting up to certain temps, so a DOT will do everything you need!

the given temps are Celsius, not fahrenheit! you bake at 200 C.

The DONENESS temp is 200°F (93°C). You do bake in the vicinity of 200°C, which is an odd coincidence.