Boiling Eggs: Everything You Need to Know

Eggs are one of the best sources of cheap, easy, delicious protein in your diet, and a good boiled egg is a great snack. But eggs are more complex than their simple appearance suggests. Different proteins make up this two-part ingredient, and the yolk and white set at different temperatures. The problem with boiled eggs is getting the right texture rather. A perfectly cooked white and smooth, moist yolk are more desirable than rubbery whites and crumbly yolks. And then there’s the peeling!

Here, we hope to give you a lot of knowledge so you can tweak to your current egg-boiling technique to yield the exact results you’re looking for.

The lore of eggs is perhaps greater than that of any other food item, and more than one chef has gone on record judging others based on their ability—or inability—to cook an egg.

—Cooking for Geeks, Jeff Potter

Hard Boiled Egg Challenges

- Rubbery whites—Resulting from being overcooked.

- Chalky, crumbly yolks—Again, from overcooking.

- Difficult to peel—The egg’s membrane fuses to the shell and egg proteins during cooking.

- Pocked or misshapen eggs—from difficult peeling

- Green outline around the yolk—caused by cooking for a long time.

Though some people claim that adding salt, vinegar, or baking soda to the water when you boil an egg can affect its final texture, in my testing, I found that the only factors that matter when boiling an egg in its shell are time and temperature.

—The Food Lab, Kenji Lopez-Alt

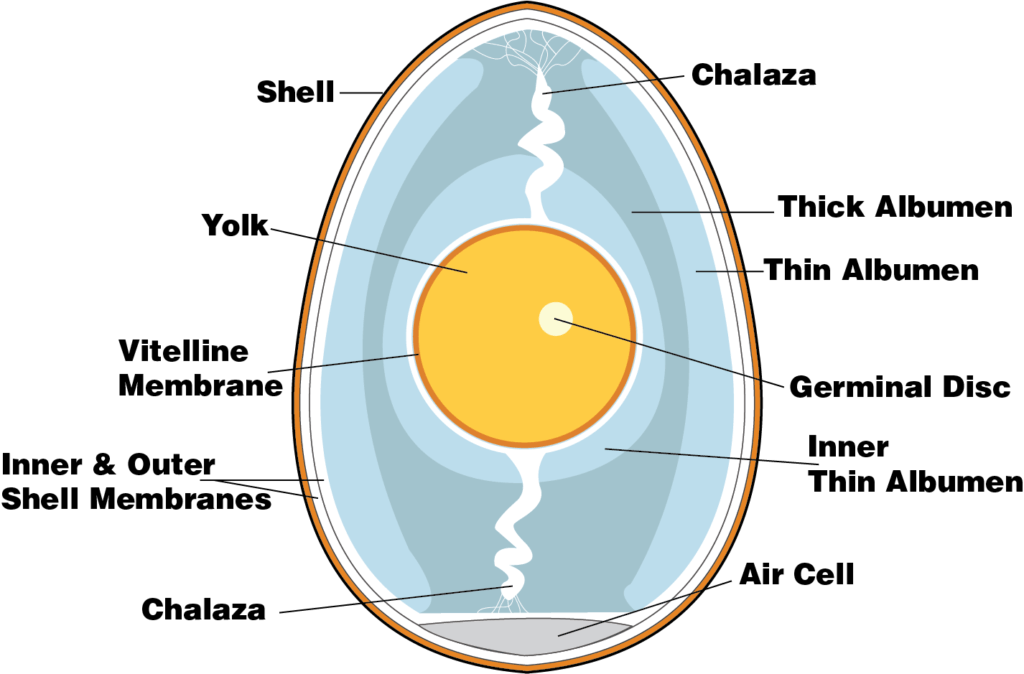

Anatomy of An Egg

Understanding Egg Proteins

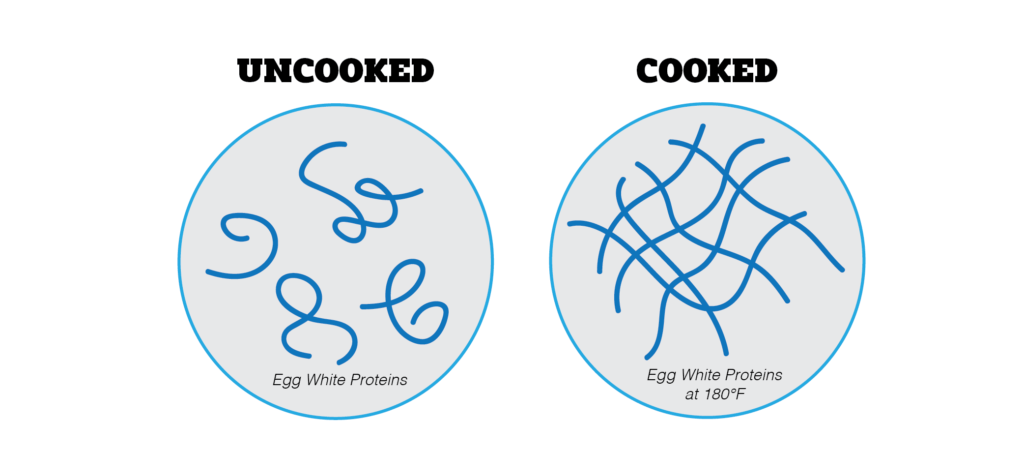

Yolks and whites are made up of different proteins that have different molecular structures and behave differently when heat is applied (collectively, their proteins are called albumen).

Just like meat, egg proteins denature and become firm and opaque. Tightly coiled, globular protein molecules unfold with the vibrations of thermal energy transfer. This unfolding is called denaturation. Once denatured, the strands of protein aggregate, or coagulate, making the once transparent egg white opaque. Boiled and fried eggs turn white and opaque, and custards become thick.

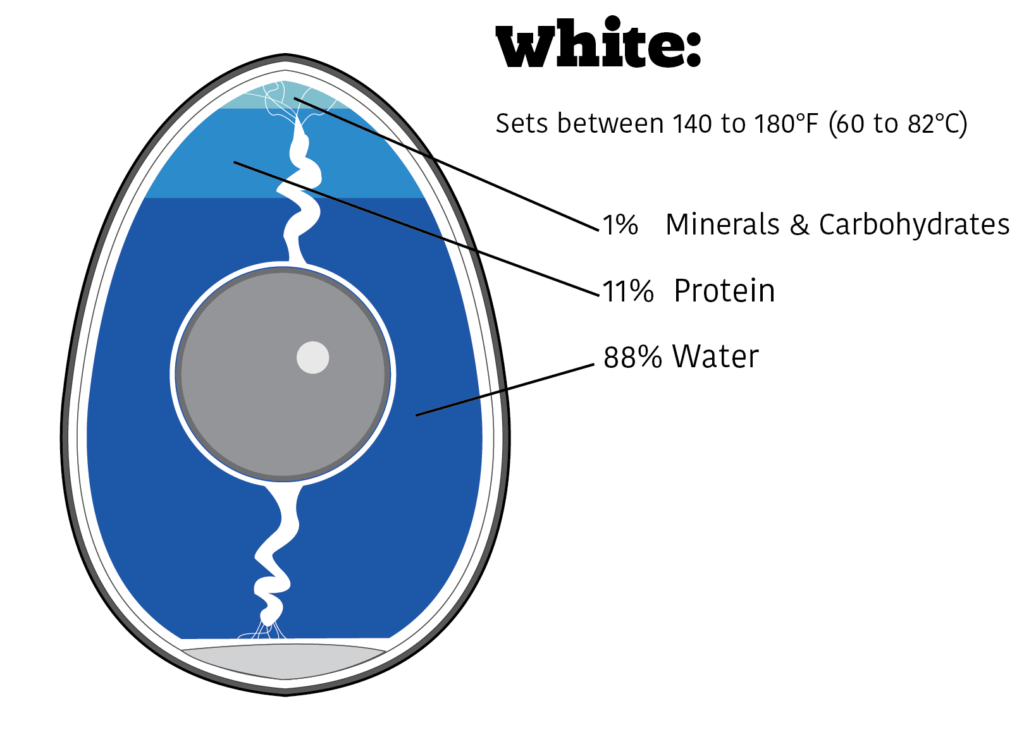

Egg Whites

Egg whites are 88% water, 11% protein, and 1% minerals and carbohydrates. The most abundant protein found in whites is ovalbumin. Ovalbumin molecules are globular and tightly coiled. When heat is applied the coiled proteins unfold and aggregate together (see illustration below). Once the proteins aggregate the egg white becomes firm and opaque. Egg whites begin to thicken at 140°F (60°C) and are fully set and firm at 180°F (82°C).

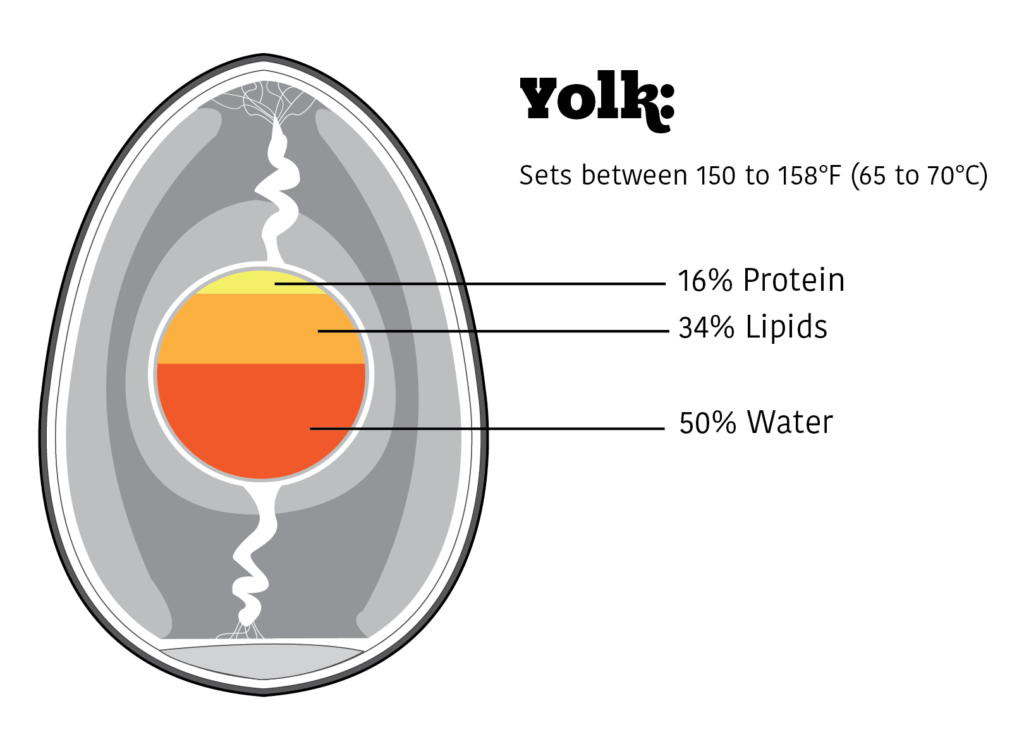

Egg Yolks

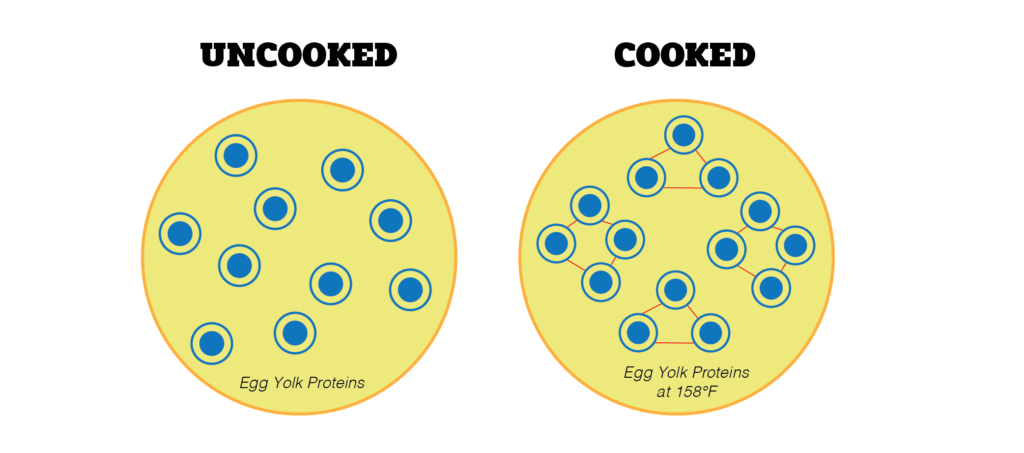

Egg yolks are composed of 50% water, 34% lipids, and 16% protein. Ovotransferrin is the predominant protein in egg yolks. Egg yolks begin to thicken at 150°F (66°C) and are fully firm at 158°F (70°C). The structure of ovotransferrin molecules is different from ovalbumin.

Egg yolks proteins can be thought of as “spheres within spheres.” The proteins are not folded over on one another, rather, they consist of larger particles that contain many sub-particles. When heated, the particles become firm and stick together (see illustration below). The texture of cooked yolks should be firm but still smooth. Overcooked yolks become grainy and chalky.

Boiled Egg Doneness: Temperature Gradients

Soft-boiled eggs are to egg doneness as medium rare steaks are to meat doneness—it’s all about temperature gradients, or the difference in temperature that exists from a food’s exterior to its thermal center. Temperature gradients exist because heat energy transfers from the outside in.

A soft-boiled egg has a firm white and a still-runny yolk just like a medium rare steak has a flavorful seared crust with a soft pink/red interior.

A hard-boiled egg has a firm white and a solid yolk, and can be thought of as a well-done steak where the protein has been fully denatured from edge to edge.

Jammy eggs lie between hard and soft boiled, with a yolk that is not fully solid, but not a pourable liquid. The outside of the yolk is fairly solid, while the center is verging on runny—the gradients really show. They’re great for snacking, of course, but they are even good for deviled eggs. The image at the top of this post is of eggs that are jammy, and they were delicious! Jammy eggs cook for a minute or two less than hard-boiled.

Eggs can be cooked in innumerable ways to suit personal preferences for doneness, but there are times when hard-cooked eggs are the best option:

- Cold salads such as cobb, potato, or egg

- Deviled eggs

- Coloring eggs for Easter

- Preparing eggs for higher-risk individuals who need fully cooked foods

Fully Cooked Without Overcooking

The challenge with a hard-boiled egg is to have a fully cooked yolk without overcooking the white. A common mistake is to overcook boiled eggs just to be sure they’re thoroughly cooked (the same mistake is often made when cooking chicken). Without a well-planned cooking method, the results are unpredictable. Some of the eggs may be perfectly cooked, while the majority are a bit overcooked and difficult to peel.

Boiling eggs: a breakdown by method and results

The most traditional method of boiling eggs is to immerse whole eggs in cold water in a pan, bring the water to a boil, and allow it to continue to boil for 10…12…15…sometimes even 20 minutes. Then remove the pan from the heat. Using this method usually results in rubbery, chalky eggs that are difficult to peel.

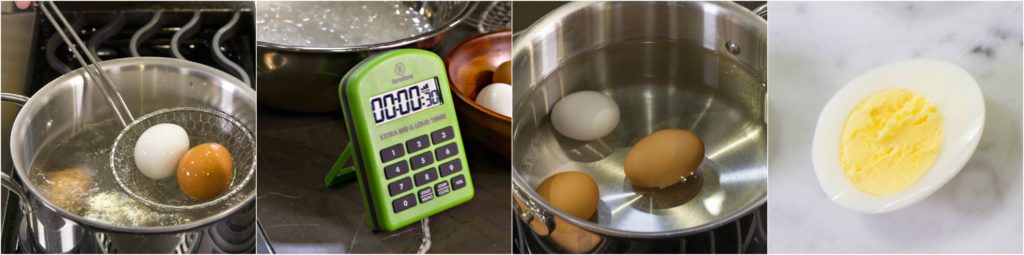

Experts recommend different methods for the most perfectly cooked boiled egg. We tried sous vide, steaming, blanch-shock then slowly boiling, and placing raw eggs directly into boiling water in addition to the traditional method mentioned above.

Each method has a specific cooking time. Use a timer like the TimeStick to wear around your neck so you know exactly how much time is left wherever you are. Or use a timer like the Extra Big And Loud. Its alarm’s volume is adjustable and can be heard in the noisiest of kitchens.

Just a few degrees makes a difference when it comes to the texture of a cooked egg.

—Cook’s Science, Cook’s Illustrated

Thermal Tip: Ice Bath & Starting Temps for Eggs

No matter what method you use, keep these to thermal pointers in mind:

Use an ice bath to stop your eggs cooking

To immediately stop the cooking process, immediately dump your eggs into an ice bath after cooking and chill them for 10–15 minutes. The ice bath is an important step to halt carryover cooking to avoiding overcooking the eggs.

It also helps the boiled eggs to retain their round shape rather than flattening on the wide end. As the temperature of the egg protein increases it expands and flattens the air cell at the wide end of the egg. If the cooked egg cools slowly the air cell reinflates, creating a small dent in the bottom of the egg before it sets completely.

Egg cooking starting temp

In our tests, we started all our eggs from cold, directly from the refrigerator. So all our recommendations and times reflect that cold start. You can play with a timer and these methods to find perfect times for eggs that start at room temperature.

Cooking eggs sous vide

- Cook whole eggs in a 170°F (77°C) water bath for 1 hour.

- Shock in an ice bath for 15 minutes.

The truly obsessive kitchen nerd’s way to do it is to maintain the water at precisely 170°F so that the yolk comes out perfectly cooked and the white is still tender.

—The Food Lab, Kenji Lopez-Alt

Result: A fully-cooked egg that is still soft. The white isn’t a bit rubbery and the yolk is smooth. The only downside is that the shell can still be a bit difficult to peel.

Boiled Starting with Cold Water

- Place raw whole eggs into a pan and cover with cold tap water. Bring to a boil and simmer for 10 minutes.

- Shock in an ice bath for 15 minutes.

Result: The whites were rubbery and the yolk was crumbly. Peeling the eggs was most difficult with this cooking method. For these two reasons, this was our least favorite way to cook whole eggs.

Boiling eggs, starting with boiling water

Place the eggs in a pot of water that is already boiling. Cook them for 11 minutes, then shock them in an ice bath for 15 minutes.

Result: Some of the eggs cracked immediately after being placed into the boiling water, leaking some of the liquid white. The whites were quite rubbery and the yolks were dry and crumbly. However, these eggs were fairly easy to peel. The eggs that cracked were a bit misshapen after peeling.

Steaming eggs—our recommended method

This method is the favorite of such experts as Jeff Potter, Cook’s Illustrated, Alton Brown, and Kenji Lopez-Alt, just to name a few.

- Prepare steamer or pot with a steam basket insert with 1 to 2 inches of water in the bottom of the pot. Put a lid on the pot and bring the water to a rolling boil before adding the eggs. The eggs should be suspended above the water.

- Place whole raw eggs in a single layer into a steamer, cover with a tight-fitting lid, and cook for 12 minutes.

- Shock in an ice bath for 15 minutes.

Result: This was our favorite method! The whites were tender and the yolk was smooth—almost fluffy as compared to the other yolks. Our favorite part about these boiled eggs was that each one was incredibly easy to peel.

Blanch, shock, boil

- Place whole raw eggs into boiling water for 30 seconds, remove and shock in ice water for 30 seconds. (In cooking terms, “shock” means to change the temperature rapidly.)

- Place blanched eggs into a pan and cover eggs with cold tap water. Bring the water to a boil and simmer for 8 minutes.

- Shock the finished eggs in an ice bath for 15 minutes.

Result: Some of the eggs cracked as soon as they were placed into the boiling water, and the texture was similar to the eggs that were cooked from boiling water and from cold water—rubbery and crumbly. Peeling was easy, though. The eggs that were cracked were a bit misshapen.

The Secret to Easy-to-Peel Hard Boiled Eggs is…Shocking!

Some say that boiling your eggs with salt or baking soda is the secret to easy-peeling eggs. But easy-to-peel hard-boiled eggs are all about temperature. The egg protein right beneath the shell needs to quickly set up, separating from the shell’s membrane—a cooking method that involves an initial shock of high heat is the way to go.

When the outermost layer of egg protein’s temperature rises gradually, it will fuse to the membrane right beneath the shell, making peeling difficult and as a result, the cooked egg’s surface will be pitted. If easy peeling is your goal, starting your eggs in cold water is the worst thing you can do.

Freshness also matters, but not how you think

But even given the shock, there’s one more thing to note that people don’t like to hear. It is this: fresher eggs are harder to peel well. The membrane of a super-fresh egg clings harder to the shell than does the membrane or an egg that has been around for a week. Or two. Use farm-fresh eggs for scrambles, omelets, and, especially, poching. But use the those eggs that have been in the fridge for a little while for boiling. Compound that with the ice bath shock, and you’ll have eggs that are easier to peel than ever.

Other thermal considerations for boiling eggs

All of these methods assume some things about thermal mass, namely that the thermal mass of the eggs is relatively low compared to the thermal mass of the water. If you have one quart of water boiling and you put 18 eggs in it, the temperature of the eggs will drag the water temp down too far for the cooking times we mention to be effective. The same goes for steaming a whole basket of eggs—by the time the steam gets through 24 eggs, the next dozen won’t get much heat. You don’t want more eggs than water in a boil, and you don’t want more than two layers of eggs when you steam them.

And all of this is compounded further by the differences in boiling temperatures at different elevations. A pot of boiling water (and therefore the temperature of a steaming pot) here at ThermoWorks is about 203°F (95°C). If you’re cooking on the coast, you’ll have 9°F (5°C) more in your water, and you’ll cook a little more quickly.

All of this is to say that you should get out your timer and cook a few eggs as practice before any important events. Be exact, and record your results in your recipes so that you can get repeatable results every time!

Top Recommended Hard Boiled Egg Cooking Method

For the best all-around hard boiled egg cooking method, we agree with experts who suggest steaming as the way to go. The shells slip right off and the eggs are silky smooth and unblemished. When cooked the appropriate amount of time, the texture of both the yolk and white is firm but still tender.

Understanding what’s going on with the food you cook really makes the experience easier, more enjoyable, and the results more delicious! Whether you’re making deviled eggs for a party or coloring Easter eggs with your family, keep these tips in mind and you’ll have the best hard boiled eggs yet.

Resources:

Cook’s Science, Cook’s Illustrated

Easy peeling eggs? Regardless of the cooking technique, do this:

Take a push pin and put a small hole on the big end.

It shouldn’t crack or leak. Yes, after the cook, shock with ice water.

But I have never had such easy to peel flawless eggs!!!

I enjoy all the info and cooking suggestions. I just did the cold water start and, as noted, the eggs were difficult to peel, ( we have our small flock of chickens and always have very fresh eggs to cook). Our go to favorite for cooking hard boiled eggs is in our insta-pot. 7 minutes for us and they come out perfect and peel very easy, sometimes the peel comes off in just two pieces! I suppose this is similar to the steaming method as the eggs are not in the water. We’re at altitude so the cooking time may be different at lower altitudes.

Hate to promote a brand! But we use an Instant Pot (electric pressure cooker). 5-6 minutes high pressure, 5 minutes of natural release, then quick release, and 5+ minutes in ice water. AND they peel like a dream!

I’ve always put the pin to the flat end (my terminology) of the egg, to prevent explosions (i.e. leaks) but to keep the egg whole by reducing the pressure when it heats, hence the bubbles when the eggs are heated. I had no idea that leaving eggs in a boil was considered normal.

The (recommended) methods I’m most familiar with, along with steaming, are putting eggs into boiling water or into cold water brought to boil. Then removed from heat.I haven’t made careful documentation but I’ve had success with both. 10+ min. done, and 8+ dark and moist in the center, & for ramen about 6min, all followed by the icy plunge. I’d like to see a study into whether an ascendance to boiling or a sudden drop into boiling is better. The basics are available easily, but I come here looking for more. I already know (forever) that you don’t let eggs boil. I think we all are above that if we are here, right?

That would be a fun test…but would still have so many variables to control for; mass of eggs vs mass of water being chief among them. Perhaps we’ll find a way to run that experiment cleanly some day.