Does Oven Accuracy Matter? The Case for Oven Monitoring

All ovens are notorious liars. They run on thermostats that turn heat on and off at certain points above and below your set temperature. This can be problematic and renders useless a hanging dial oven thermometer. We’ve posted before about the process for testing your oven’s accuracy using Square DOT®. But people have asked us why. Does it matter, after all, if my oven is off by, say 25°F (14°C)? Yes, it does! And here we want to show you how. Oven accuracy will greatly affect the outcome of your cooking, especially when it comes to baked goods. Take a look at our explanation and experiment below, then get yourself a Square DOT and improve your cooking!

Problems with inaccurate ovens: a theoretical rundown

To understand why oven accuracy matters, we’ll take a close look at what happens when we bake something like, say, cornbread (or a cake or bread…). When we put a batter or dough in an oven, the material begins going through the stages of baking, which are as follows:

- Gases form

- Gases are trapped

- Starches gelatinize

- Proteins coagulate

- Fats melt

- Water evaporates

- Sugars caramelize

- Carryover baking

- Staling

Though these are all fascinating and worth talking about in some context, in the context of this explanation we need only examine the first four stages.

Gases form

For gases to form, the oven must be hot enough to induce any gas-forming chemical reactions—the acid and base in baking powder interacting, for instance—or for steam to begin to form. The heat causes any gasses present in the mixture to expand, be that trapped air, carbon dioxide from reactions or yeast, or newly created steam. If the oven isn’t hot enough, those gases either won’t form or won’t expand enough.

Gases become trapped

Gases become trapped as they form, making this stage a corollary to the first. The networks of proteins in your dough or batter trap the gasses, holding them while they expand. The proteins can be gluten or egg and milk proteins. This is more of a mixing problem than a temperature problem, but it is not insignificant, as we’ll see in a moment.

Starches gelatinize

The gelatinization of starches is where oven temp really starts to matter. Starches begin to gelatinize at temperatures as cool as 105°F (41°C), but really kick in at 140°F (60°C). In this process, they absorb water from their surroundings, creating the beginnings of structure. Think of when you boil a pot of oatmeal or grits. It’s very fluid, very wet, then as the starches gelatinize, the mixture thickens. It remains pliable, yes, but if you use less water, it could become quite stiff. In our baked goods, it’s quite stiff, usually.

Proteins coagulate

Finally, there is protein coagulation. You know what happens when you boil and egg or overcook a steak. Proteins that were once soft become almost immoveably firm. Protein coagulation creates a much more permanent state change. In bread or cake, it creates sponginess, springback, chew.

Why temperature matters

If the oven is too cold

Let us assume that the oven temperature is too low. In that case, the starches will not gelatinize as quickly nor will the proteins coagulate as readily. While the starches are not gelatinizing, the gases are expanding and rising up through the medium and slipping away. The bake’s structural basis will be negatively affected, setting up worse things to come when the proteins finally coagulate.

With delayed gelatinization, the “thick grits” of our cake will not be holding the gas bubbles up and wide open, and the proteins will set in place. The result can only be favorably compared to a hockey puck. A bread or cake cooked too low will seem almost as if there were no leavening, because, in the end effect, there was none—it all escaped before the body could set. In fact, if you’ve ever had a cake fall in the oven, it was likely that the oven was too cool to set the cake in place properly. Yes, your mother blaming her fallen cakes on your rough-housing near the kitchen was wrong! It was the oven’s fault all along.

And what if the oven is too hot?

If the oven is too hot, we have other problems, especially if we’re trying to make a cake for decorating. A very hot oven will indeed create gases, lots of them including more steam. But with high heat, the starches will gel while the gases are high, and the proteins will follow suit. In fact, it can trap the overly-inflated gas bubbles, as well, making for an uneven crumb texture.

If you’ve ever cooked a cake that was excessively domed, or even peaked in the center, you can know that your oven was cooking too hot—even if it said it was cooking just right.

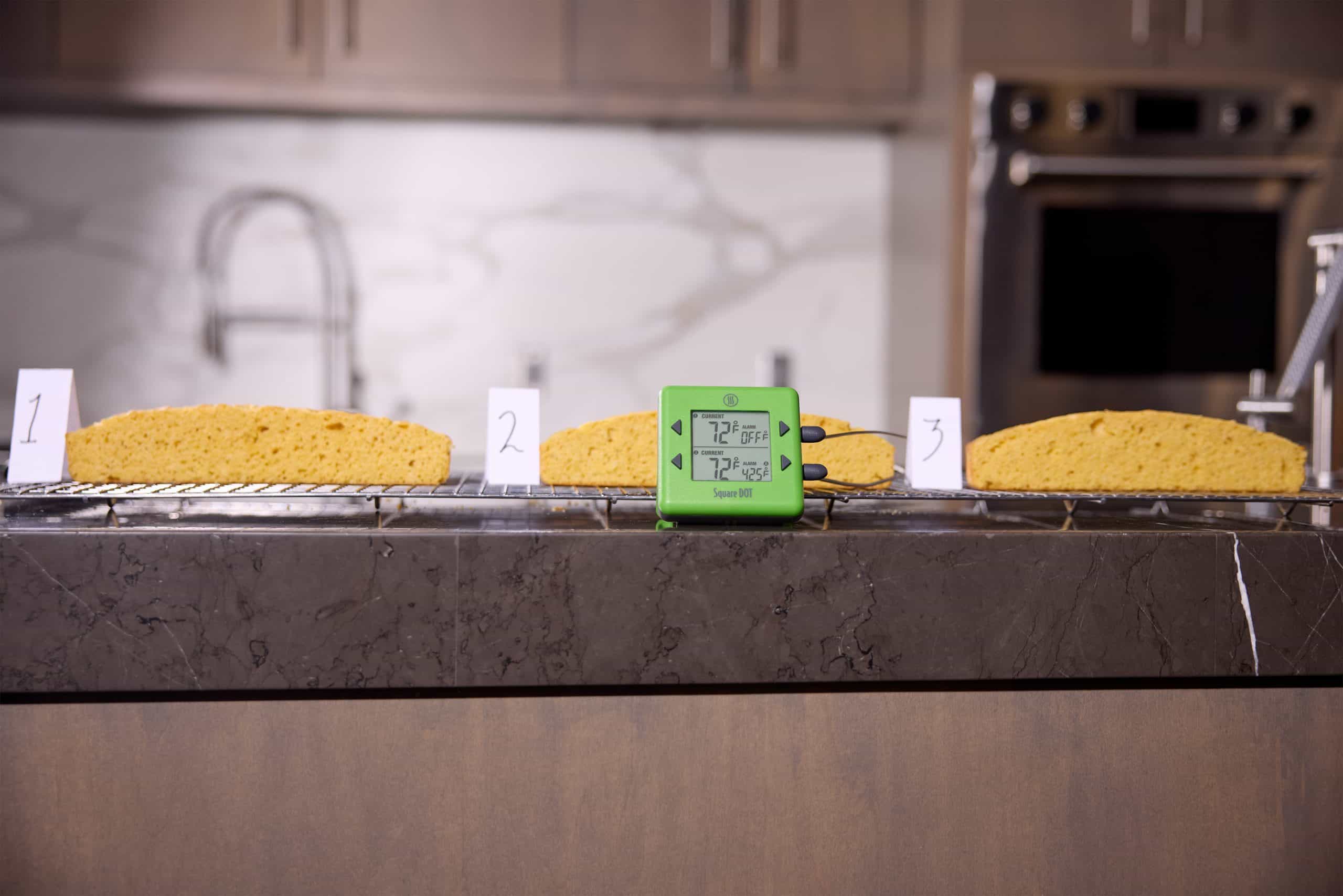

Experiment: 3 cornbreads, 3 temperatures

To demonstrate the effect that temperature has on baking (though it also affects roasting and other oven-cooked foods), we made three identical batches of cornbread. We cooked the first one 25–50°F (14–28°C) cooler than recommended, the second one at the recommended temperature, and the third 25°F (14°C) hotter than recommended. We chose those ranges because oven thermostats can easily be off by that much. In fact, even though I used Square DOT to adjust the temperatures to actually be where we wanted them to be, the oven still decided to drop during our first batch, which is why it is off by up to 50°F (28°C).

In the slider below, you can see batches 1, 2, and 3, moving up from under-temped to over-temped. All three were taken from the oven at roughly the same doneness temperature.

Cake 1 you can see is lumpy on top—its skin didn’t get stretched by a rise—and it’s very dense. It was not as fun to eat as the others were:

Cake 2 has good crumb structure, was a good density and turned out just right. Also the bottom was more browned and tasty. Aside from a little glob of undermixed flour, this cornbread turned out just right!

Cake 3 has bigger bubbles in the crumb, a result of the high-heat cook. It is not, in this case, massively more domed, but if you look carefully at the edges, they are raised, peaked a little around where the pan was. Take a closer look below:

The pan in this case got so hot that it inflated the edges and cooked them in place, creating an interesting shape. Cake 3 was also at a higher temperature by the time the initial timer went off. If we’d waited any longer, it would have started getting dry. The odd shape didn’t make it bad like the undercooking did, but for presentation purposes, it could have been better.

Oven accuracy matters. Check yours.

We hope this helps you understand how important oven accuracy can be. Your cooking might be one temperature adjustment away from perfection. Grab a Square DOT, learn to use it to check your oven, and enjoy cooking success—cooking happiness—like never before.

See On Baking, a Textbook of Baking and Pastry Fundamentals, Labensky, Martel, Van Damme, 2nd edition, p. 57↩