BBQ 101: An Introduction to Smoked Meat, part 1

Barbecue is perhaps the iconic American form of cooking. We borrowed everything else, but the various regional styles of BBQ in America are ours. Today, the interest in BBQ is growing like never before, with local competitions springing up all over and slow-cooked, smoked meats making their way from hard-to-find back-woods shacks into manicured suburban neighborhoods. Americans love barbecue and are expressing that love by learning how to do it. If you’ve decided to learn the craft, or even if you have cooked a few butts in your day, you’ve probably come across the million blogs, forums, books, and magazines that are available to those that want to perform carnivorous alchemy, and you’ve likely been overwhelmed by it all. I know I was.

That is why we’re bringing you this BBQ 101 Guide. In this series, we’ll distill the basics of what you need to know about smoking meat, from smoker to sauce. In Part 1, we’ll go over the history and origins of barbecue as well as some of the major thermal processes, from smoke and combustion to collagen dissolution and smoke rings. So strap in, there’s a lot to cover!

Contents:

What is BBQ?

First, there’s one thing we need to clear up: Grilling and barbecuing are two different things. I remember talking to a pitmaster from Tenessee who had moved to Utah and hearing about how his new neighbors had invited him over for a barbecue, for which he was very excited. On arrival, he and his wife looked at each other with disappointed chagrin as they surveyed the stacks of burgers and hotdogs and realized that the well-meaning neighbors meant a grilling party, not a barbecue. We’ve written a whole post on the topic of the distinction between grilling and BBQ, but for the sake of brevity, we can boil it down to one key difference: the cooking temperature.

Grilling is a high-heat cooking method, while BBQ is a lower heat method. If you’ve heard people talking about “low and slow” cooking, that is the heart of barbecue.

Where did BBQ come from? There is no straightforward answer to the question, and entire books on that history have been and still could be written on the subject because there are many cultural influences and historical twists in the origin and regionalization of American barbecue. The name “barbecue” comes through Spanish from the native Arawak barbacoa, meaning “a wooden frame on posts”—a reference to the drying and cooking of meats on a raised bed over hot charcoal. American barbecue most likely started with slaves brought from the Caribbean.

As the cooking method spread, it changed, morphing with local flavors and the availability of local ingredients. In regions across the American South and Midwest, sauces were created, regional favorites for cooking wood choice emerged, favorite meats became local standards, and rubs evolved as they moved not just from state to state but even city to city and kitchen to kitchen.

Today, slow-smoked barbecue is a staple of American regional cuisines. From sticky St. Louis ribs to vinegary North Carolina pulled pork, the long, slow application of heat and smoke to meat is easily the most celebrated of America’s home-grown culinary traditions.

Low and slow: BBQ temperatures and smoke

If you have listened to anyone talking about barbecue cooking, you have certainly heard the term “low and slow” being thrown around as if it were an article of faith. If you’ve ever wondered why that is, then your ship has come in…

Collagen in BBQ

Classic BBQ meats are chock full of collagen—a tough connective tissue that is plentiful in animal muscles that undergo heavy use. (Beef tenderloin is tender because it is a muscle that is almost never used, while brisket is used all day, every day by the cow, meaning that it will have a lot of tough collagen.) The long, tightly wound strands of proteins that compose collagen’s sinewy structure provide strength and endurance for the animal but make things difficult for eating. If you were to cook the classic BBQ meats quickly over high heat, serving them medium rare like a steak, they would be as chewy and tough as grilled rope—you wouldn’t be able to eat them.

Collagen, then, seems like a terrible thing to work with in the kitchen, but it is not! In fact, it’s the collagen that is responsible for barbecue’s delicious meat alchemy.

When collagen is cooked slowly at lower temperatures for long periods of time, an astounding thing happens. Its long, tightly bound fibers begin to unwind, releasing water and melting into soft, silky gelatin. It’s the ultimate makeover. Gelatin offers no resistance to the teeth and can hold up to 10 times its weight in juices!

With the collagen melted and replaced by fully hydrated gelatin, the BBQ meat becomes bite-through tender, juicy, and indescribably delicious. This miraculous process begins at about 160°F (71°C) internal temperature in the meat but really picks up at 170°F (77°C), with the collagen melting faster as the BBQ slowly approaches 200°F (93°C).

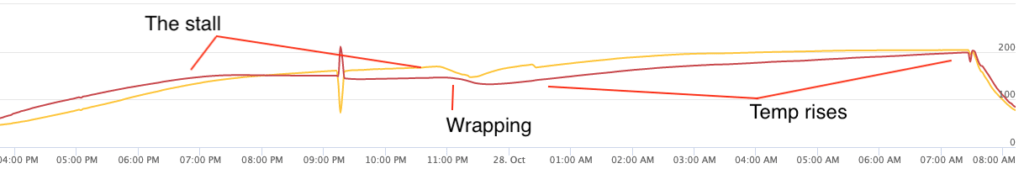

The stall

There is one more thing to know about how proteins react in BBQ cooking, and that’s the stall.

The stall happens when the protein fibers in the meat contract (when the meat is going through and passing “well done”), expelling water from within. That water makes its way to the surface and evaporates in the heat of the smoker, causing evaporative cooling. In essence, the meat sweats.

That evaporative cooling keeps the temperature of the meat from rising for a long, long time, just as sweating cools you down when you exercise. (The stall on a large brisket can last over 6 hours!) The stall typically starts at about 150°F (66°C) and can run up through about 180°F (82°C) on all the BBQ beef and pork cuts. If you are monitoring the temperature (as you can with our Signals or Smoke + Gateway and the amazing ThermoWorks app) you’ll see the temperature plateau off, staying maddeningly flat for hours and hours….

If you want to speed through the stall, you need to create an environment where the water on the surface of the meat can’t evaporate into the air. This is done by wrapping your BBQ meat in either foil or butcher paper.

Wrapping your meat creates a micro-climate around the surface of the meat that rapidly reaches 100% relative humidity, meaning that no more evaporation can happen. The meat will continue to expel water from its tightening muscle fibers, but it will not be venting that water to the air and cooling itself down. This can shave hours off of your cook, and that is its greatest merit. However, it can, if improperly done, moisten the crust that forms on the outside of smoked meats (usually called the “bark.”)

To preserve your bark, make sure the bark has set well before wrapping. A simple scratch test is pretty effective. If the dark smokey bark buildup doesn’t just scrape off when you scratch it with your fingernail, it is much more likely to be able to withstand the increased humidity of the wrapping. If, on the other hand, you wrap before your bark “has set,” you won’t get it back.

The great thing about how this all works out is that while it seems as if the meat will dry out by squeezing out all its water during the stall, just in time the collagen starts to unwind more rapidly, creating gelatin that can readily absorb the water being released and keep it from going to waste. Thus brisket, which is cooked way past well done, is both juicy and tender in a way that can actually put a medium rare steak to shame!

BBQ smoker temps

In general, most barbecue cooking is done with pit temps in the 225–275°F (107–135°C) vicinity. That range allows the internal collagen to “melt” into gelatin without the exterior of the meat drying out. Those relatively low temperatures may take longer to cook at, but the time sacrifice is well worth the results.

Proper temperatures don’t happen by themselves, however. As we’ll see below, the kind of fuel and the kind of smoker you are using can greatly affect the stability of your smoking temperature. Monitoring your smoker’s air temperature is not as simple as just sticking your hand in a hot box of air and saying “yeah, that’s hot!” For the best results, and results that you can reproduce every time, you need real measurements. You need a thermometer with an air probe.

We’ll cover measurement in more detail below, but to help understand why it’s important, you should first also understand that cooking in this range not only allows the meat to cook properly but it also affects the kind of smoke that is created in the combustion of your fuel, and that affects the taste of your BBQ.

Kinds of smoke

BBQ gurus will spend a lot of time talking about the right kind of smoke, but what does that mean? Combustion of wood and charcoal produces heat, gasses, solids, and water vapor, and those byproducts affect the way barbecued meat tastes. Wood and charcoal burn in different ways based on the amount of available oxygen—meaning you can change the character of your smoke by changing how much air it has access to.

A fire that is starving for air will produce a sooty, black smoke that tastes acrid and off-putting on food. A fire with plenty of air will have very efficient combustion, producing white, billowy smoke. That’s fine for cooking smaller cuts, but not great for longer cooks because the smoke flavor can be more intense and too heavy if meats are exposed to it for a long time. What you want is a fire that has a Goldilocks amount of air..not too much, no too little, but just right. If you hit that level, you’ll get a light blue, slightly billowy smoke. That pale blue smoke is BBQ gold.

Smoke from wood or charcoal for cooking can range from bluish, to white, to gray, to yellow, brown, and even black. The most desirable smoke is almost invisible with a pale blue tint…Blue smoke is the holy grail of low and slow pitmasters, especially for long cooks.”

AmazingRibs.Com

The smoke ring—what it is and what it tells us

And while we’re talking about kinds of smoke, we may as well talk about smoke penetration and the “smoke ring” so often associated with good BBQ. On properly executed smoked meats you can see a red ring just below the surface of the meat, hovering between the bark and the brown-grey cooked meat. That red ring is called the smoke ring. Why is it red? Because of nitrous oxide!

When wood or charcoal burn, they produce nitrous oxide as one of the byproducts of their combustion. That nitrous oxide combines with the myosin proteins near the surface of the meat, changing their composition. Myosin is the protein most responsible for meat’s red color, and by changing its structure, the nitrous oxide prevents the myosin from denaturing in a way that turns brown. Thus, it stays red or pink. (It is the same reaction that keeps ham and corned beef red instead of turning brown when cooked.)

The smoke ring also points us to an interesting truth: The depth of the smoke ring is the maximum depth of smoke penetration, and therefore of flavor penetration from the fire.

It doesn’t matter for how many hours you smoke your pork butt or how perfect your fire management is, the dead center of the butt will not taste like smoke. The gasses and particulate matter that smoke is made of just can’t penetrate the muscle fibers that far down. In fact, almost all of the penetrative smoke flavor in barbecued meats is achieved in the first couple hours of cooking.

That’s why you can put a few chunks of hardwood on a charcoal fire at the beginning for the sake of smoke and not have to add more wood later on. The flavor will go just as deep as if you had smoked it over wood for the whole cook. Now, it is a popular thing to add some more hardwood at the end of a cook to throw a little more smoke flavor on the outside of the meat, but that will be surface smoke, not deep smoke.

Let’s talk BBQ thermometers!

Barbecue is all about temperature control—keeping the smoker at the right temperature, applying various anti-stall methods, and even knowing when to pull your meats from the heat. The biggest necessity for successful barbecue, then, no matter the smoker type or fuel, is an accurate, durable BBQ thermometer.

While most pitmasters swear by their instant-read thermometers like the Thermapen® for spot-checking internal temperatures (and even just testing the resistance of the meat with just the probe); when it comes to BBQ, leave-in probe thermometers really shine because you can track changes in temperature in both the meat and the smoker itself over long periods of time. You can set alarms and get alerts when certain temperature thresholds are met or exceeded. And you can also use them without having to open the lid/door to your smoker to check on things, releasing precious heat and precious smoke out into the world and away from your BBQ.

You can find a durable, accurate ThermoWorks BBQ alarm thermometer for just about any budget, from our DOT® to our ThermaQ® Blue, with a wide assortment of probes to fit your needs. A great option for a BBQ cook of any skill level is the Smoke X2™, which has long-range capability that can reach the accompanying receiver, even if the thermometer is in the yard and you are in your house. Or you can use Signals, a 4-channel thermometer that can connect to your Wi-Fi directly so that you can access your cook via the cloud. But no matter what thermometer you get, get a thermometer. Having the control over your cook that comes from that thermal knowledge will improve your barbecue skill faster than anything else.

Types of smokers

Whatever temperature it is that you need for your particular cut of BBQ, and whatever thermometer you use to track that temperature, the heat has to come from somewhere, and that brings us to fuel. Each kind of BBQ fuel has its advantages and disadvantages, so a run-down on each is a good idea.

Stick burner

Stick burners are smokers that use actual chunks of wood for fuel. They are usually, but not necessarily, offset smokers (about which you will be able to read in Part 2 of our BBQ 101 Guide). Depending on the size of the smoker, these may burn anything from large chunks and small logs to split wood and thin tree limbs. They are often finicky and require fire craft and close attention to keep the fire burning and to keep the smoking chamber at the right temperature.

Because of the uneven burning properties of different wood chunks, a BBQ alarm thermometer with an air probe like the ThermoWorks Signals or Smoke X is a necessity for cooking with a stick burner. They are not great for beginners and are often the realm of well-seasoned pitmasters. However, the smoke flavor that can be achieved in a stick burner is really unparalleled. It takes work, but the results can be fantastic.

Charcoal smoker

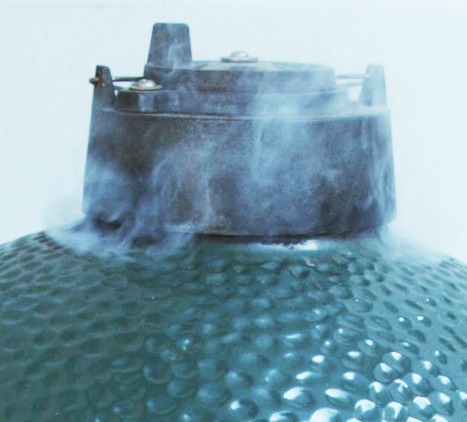

For a slightly easier fueling method, consider a charcoal smoker. Charcoal still requires that you pay attention, but it doesn’t require the kind of fire craft skills needed for a stick burner. Charcoal briquettes burn evenly and are a great way to start out with BBQ, but most barbecuers prefer lump charcoal because it burns hotter for longer and gives off better tasting smoke.

Of course, even lump charcoal doesn’t produce as much billowy smoke as wood, so to compensate for the lack of flavorful smoke, weekend pitmasters will often add a chunk or two of hardwood to the fuel bed at the beginning of the cook. The wood chunk smolders and makes enough smoke to flavor the meat but is not the primary source of fuel. Even without extra wood for smokiness, you can still get a lovely smoke ring with a charcoal smoker. The products of combustion that create it are still present in the gasses escaping from the burnt charcoal even though there is less visible smoke.

Charcoal smokers are easier to run than stick burners and are great for intermediate-level barbecue cooks. The fuel burns at a more constant rate, making temperature control easier, but still necessary. Monitoring the air temperature in your charcoal smoker is essential, and a tool like the four-channel Signals or the two or four-channel Smoke X makes that easy to do. Even a pile of lump charcoal can burn out before the BBQ is done and require you to add additional charcoal. When your pit temps start to plummet (often in the middle of the night) you’ll want to be the first to know!

If you want even more control of the temperature in your cook, you might want to pick up a Billows™ BBQ control fan. This fan attaches to just about any smoker and takes the reading right from the air probe of Smoke X, Signals, or ThermaQ® 2. You can set the temperature on the unit or, with Signals, from the app and the fan will feed or starve the fire to reach your desired temperature.

Pellet smoker

The easiest of all smoker options is the pellet smoker. Pellet smokers use pelletized sawdust for fuel, pulling them from a hopper via an auger into a heating pan where they are burned via a hot plate or some other method of combustion, creating smoke. A processor monitors the smoker temperature, adding more pellets for burning when the temp drops too far. The advantage of this smoker is its extreme ease of use—you just turn the dial for the temperature you want like with an oven in your kitchen. They are not, however, perfect.

The internal thermometers on many pellet smokers are often inaccurate, sometimes by as much as 50°F (28°C). If you go this route, like so many do, you should regularly test your pellet smoker’s temperature accuracy (just like you should check your oven’s accuracy—and a ChefAlarm® can help with that!)

Also, some BBQ lovers say that the smoke flavor imparted by a pellet smoker is not as strong or tasty as that obtained by use of, say, a stick burner. That may be a matter of taste, and I can vouch for many delicious meals that have come off of our pellet smoker. Ultimately, if you’re new to BBQ and want to focus on the meat rather than managing the fuel source, a pellet smoker can be a great choice.

Summary

If you want to perfect the traditional art of American barbecue, you need to be aware that it is a highly temperature sensitive process. Yes, it originated in a pre-technological world, but it can be more easily perfected with our modern understanding of science and technology. Understanding the processes of collagen dissolution and the stall gives you the brain-power you need to make choices about your cook. And having a high-quality, accurate thermometer like the Signals or Smoke X is a necessity will help you to keep everything on track, from the kind of smoke you’re making to the pull temperature of your meat, no matter what you’re using for fuel.

Dust off the smoker, lube up the hinges and check your thermometer batteries…BBQ season is back in session!

Check out Part 2 and Part 3 of our BBQ 101.

Shop now for products used in this post:

Thanks that was good information

I’m so looking forward to this I’ve been BBQ sence 1960’s u can always learn more

Smoked meat has ruined the BBQ world and should not be used when referring to BBQ.It is not BBQ, it is smoked meat. BBQ is cooked on a pit over coals. I hate smoked meat, my children gave me a Pit Barrel. I tried using it according to instructions, I got smoked meat, now I use it like a pit for small cooking and my 6ft x 6ft pit for large cookings.

I will not visit a resturant if I know it has smoked meat. That eliminates most so called BBQ resturants.

Don,

That is an interesting distinction and one that holds some real weight! of course in the popular speech, BBQ and smoked meat go hand in hand, but I absolutely get where you’re coming from. Places like Rodney Scott’s in Charleston where they pre-burn the wood and shovel the coals under the whole hogs are excellent representatives of the original BBQ culture. As I said, whole books could be written about BBQ history and the divergence from pit-over-coals cooking is something I’d be very interested to know more about.

I totally agree Rush. They have intellectualized all the BBQ flavor out of REAL BBQ. I don’t even buy it any more because all of the oldtime African American Barbeque joints have joined the horrible SMOKED meat crowd. Everyone who knows what BBQ is supposed to taste like do not like the smoked IMPOSTER. We bought some a couple times for special occations, and nobody liked it. Couldn’t even get them to take some home and we were stuck with all of the tasteless leftovers … Brick, our dog, didn’t even like it, so we threw it away. LOL, and they have the nerve to put an outrageous price on it … like it tastes good. If you can’t smell real BBQ for blocks around, it’s just not BBQ. Whoever did this to our American cuisine should be arrested, prosecuted and sentenced to LIFE in jail.

Over the years I’ve tried a number of meat thermometers .The cheap ones only prove you get what you pay for. Two in particular were a mere 40 degrees in disagreement! Then I discovered Smoke. I’ve gone nuts even getting the Gateway (Which I have yet to use – I’m always home when I smoke but I thought if I went to the store while cooking that might come in handy). The Smoke also allows me to monitor the internal temp of my pellet smoker or other smokers at friend’s houses. The article is correct, my pellet smoker is a spendy one but the temperature isn’t as accurate as I would like.

Thank you for this fantastic article! They say live and learn… details which no one would know to look for and follow. I am sure many many have no idea of the difference of barbecuing and grilling as I did not till seeing this article. Thanks again!

While discussing wrapping the meat to decrease stall time, you mention that if not done properly it can lead to bad “bark”.

What is “bark”?

Sal,

Of course! The bark is the seasoned coating of spices that forms on the outside of your meat when you BBQ. Bark is formed by the cooking and coagulation of proteins that have mixed with the seasonings on the meat’s surface. When properly formed, it will adhere to the meat and not let go. May BBQ masters recommend a “scratch test” for the bark, whereby you scratch the surface and see if the bark comes off or not. If it will not scratch off, then it is properly formed.

We’ll go more into that in a section in a later segment.

Great article. Not pushy on the Thermoworks products. I like that.

I own many of your products and many types of smokers/grills etc. if you are serious about your end product then buy the best. But Thermoworks products.

No I’m not a shill for the company just a guy who works hard for his money and doesn’t like to ruin good meat because of a temperature oversight, of which I have many times, pre Thermoworks, in the past.

The commentor may be talking about ‘bark’/covering that is on trees. The other bark is a sound made by dogs. I was born in 1931, in a rural area, (aka: country) of East Texas, and you get to know and identify the different vegetations, wild life, etc. Back then much that we ate was wild and we had to learn, early on, what was eatable and what was poisonous. SMH, God was with us.

This made for some very good reading , was wonder about your thoughts on using a Electric Smoker ? I recently build my own Electric Smoker with a smoke generator and have been having very good results ( low and slow makes for the best cooked meat for me).Just purchased the smoke II from you and looking to use it this week ,I can say right out of the box it is so much better than anything I have seen. Thank you

Gerry,

I’m glad you’re enjoying your new tool from us! As for electric smokers, we’ll spend a little time in the next section talking about them. Anything that keeps a constant low temperature and creates smoke from hardwood is going to be great, so I say run with it and if you made your own, all the better!

Great review to start the season in Indiana

Thank you so much for this wonderful refresher course, low and slow is the ultimate for great Barbecue.

If you are really into meat , Thermoworks is the only way to go!

I have gifted several products to friends that I love , believe me, there is nothing out there that is better .

The web site is great , if you mess up and need a new probe , you receive it in a couple of days , no problem ! Just register your purchase , and they send you discount sales all the time along with great articles just like this .

Thank you! Happy cooking!

Great article!

Thank you!

What about using gas as a fuel source? I’ve had some success (still learning!) using my big grill for smoking. It has 7 or 8 burners with the far right one firing a lidded smoke box. I adjust the next two or three burners (on the right), leaving the left burners off. I put the meat on the unlit left side of the grill (treating it as a sort-of offset cooker), adjust temperatures (lit burner levels) appropriately to maintain 250 degrees on the meat side of the grill and let it go (with some damp wood chunks in the smoker box). Comments? Or does using gas do something to the BBQ flavor due to its combustion by-products?

Gary,

That is a great way to BBQ. I’ll be sure to add a bit about that in the next part.

The reason this isn’t talked about as much is probably the BBQ community’s heavy sense of traditionalism. But there’s nothing wrong with it at all!

It’s not about traditionalism, it is about flavor. Of course smoke has always a part of BBQ, but you don’t get the BBQ flavor without coal and wood (Mesquite chips is my favorite). If it blazes up while cooking with coal, just dash/splash a little beer on it. Smoked meat has no flavor. I like Smoked Brisket, but smoke does nothing for my taste buds for other cuts, including Prime cuts. Real, old time BBQ cooking methods were the best. Now it is not worth the bother or the money. The original cooking method was even better without sauce, because the sauce also takes away the real BBQ flavor. I even like BBQ cooked with coal only, much, much better than smoke only.

Thanks Enjoyed the article and all its information. One question–I noticed the rig (looks lie a wood block) with 3 probes inserted. Please comment,

Ah! yes, that was for a controlled experiment we did on some briskets last year. I wanted the same spacing for my probes across three different cooks. I took a square wooden dowel, drilled holes for the probes and inserted them into the brisket. For the next cook, I was able to recreate the probe placement much more exactly than if I had eyeballed it. Not much utility for the home cook, but it was a good piece of best lab practices for us!

What about meat quality? I live in the Western NY area and I find it difficult to find local meats that are of high quality. Or at least, that’s what I think. I have made ribs so many times I feel I can make them in my sleep. And with some of the fancy gadgets I have to control the temperature in my Weber Smokey Mountain I feel the end result should be more consistent than it is. I’ve blamed this on the meat quality but maybe it’s really me. In my first rib competition I special ordered spare ribs from one of the higher quality butcher shops in the area and the end result was spectacular. Best ribs I’ve ever made and the most expensive too. A typical rack of ribs is normally around $10 to $12 around here but these were closer to $25. What should one look for when choosing meats for BBQ and how do I go about finding the right place to get them?

Tom,

We’ll go into meat selection more in Part 2, but suffice it to say that you are right. Higher quality meat does yield higher quality BBQ. I have near me two grocery stores where I can buy meat for our cooks and I have found that one of them consistently provides quality meats while the other’s meats, nominally of the same grade, are far less tender and flavorful.

For weekend ribs, that doesn’t matter as much. But for competition, yes, you want to get the highest quality meats you can find. Many BBQ teams will special order their meat from halfway across the country just to get the kind of product that they want.

I’d try to maybe find a local grower. Check a farmers’ market or look for a local CSA meat producer. Buying a half a cow is a big upfront cost but can yield huge dividends in cost per pound savings as well as quality meat. Otherwise, it’s pretty much the mail order trade.

I hope that helps! Happy cooking!

Good information, well written.

Should include gas smokers, which many, including me prefer. The new thermostatic temperature control models make these the easiest of all to produce good results.

Really enjoyed the article. In fact I will down load and pass on to others this well thought out and articulated essay and the follow ups as well. This seams to be geared towards the back yard Q’er. Because of this a suggestion for future topics may be about choosing the right equipment. Specially for charcoal and “stick”. There are so many from independent makers to those sold in hardware stores and the like. Some are great and others aren’t worth the money paid. Thickness of steel and how air tight they are play into the overall cooking experience. The vertical, offset, reverse flow, barrel, pit, and ceramic (Kamodo style). Not that any of these is better than the other but the benefits and drawbacks, and what to look for. These might be great, but then you end up with a book. Oh well I thank you for the article and I am looking forward to your next installment.

Grillin,

You’ve read my mind! Information like that is on its way…

Great information! Thank you for taking the time and effort to write it.