The Thermal Dirt on Potatoes: Potato Doneness Temperatures and More

If there is a starch that rules the American table, it is the potato. They go with almost any main dish, and are the very picture of versatility—you can, as Master Samwise puts it, “boil ’em, mash ’em, stick ’em in a stew.” If you’ve followed this blog for long, you already know about our love for hot, golden, crispy fries.

But given how common potatoes are in our diet, people know relatively little about them, especially the ways that they interact with temperature. Here, we’ll give you all the dirt on potatoes, from types to temps and beyond. Let’s get serious about spuds!

Potato basics

The potato is a member of the nightshade family (related to tomatoes, chilies, and tobacco) and was originally native to the northern reaches of South America. It is a tuber that grows on the roots of the plant, acting as nutrient storage for the plant. There are thousands of cultivars of potato and they are now eaten across the globe. In fact, the potato is the world’s largest vegetable crop.

Potatoes are quite rich in vitamin C and potassium (with more potassium than bananas!). They are also chock-full of energy. There is a reason the peasants of Europe took up the potato with such fervor once it was introduced to the continent. A vegetable that is easy to grow, hardy, and inexpensive, that also prevents scurvy while providing energy for a full day of field labor? Yes, please!

If that sounds like a golden food, then you’re paying good attention. It is not, however, perfect. As a member of the nightshade (solanum) family, the plant has developed certain defenses against pests. They can contain high levels of the toxic alkaloids solanine and chaconine. These bitter compounds form in the potato when they are exposed to light or when they experience stress while growing. Because potatoes also turn green when exposed to too much light, a green hue can be a sign that potatoes have been exposed to too much light and could, therefore, have more toxins than you should eat. When you encounter green potatoes, either discard them or peel them deeply, past the green. Or if your potatoes taste very bitter, don’t eat them. They could be toxic.

How to store potatoes: temperature matters

Potatoes can be stored in the dark for months, during which their flavor intensifies; slow enzyme action generates fatty, fruity, and flowery notes from cell-membrane lipids. The ideal storage temperature is 45–50°F/7–10°C. At warmer temperatures they may sprout or decay, and at colder temperatures their metabolism shifts in a complicated way that results in the breakdown of some starch to sugars.

Harold McGee, On Food and Cooking, pg 302

Those temps are quite cool without being cold, and explain how farmers used to get through the cold months when nothing was being harvested—fresh taters all winter long in the root cellar!

Many basements run at a cool temp. To know if your cellar is optimal for spud storage, stick a ChefAlarm® with a probe in there and let it come to temperature. Then clear the min/max function and let it sit for a day or so. Read the minimum and maximum temps encountered and you can easily see how well suited your basement is for root-cellaring your potatoes. The closer you can keep your potatoes to that optimal temp of 45–50°F (7–10°C), the better.

Mealy vs waxy potatoes: what’s the difference?

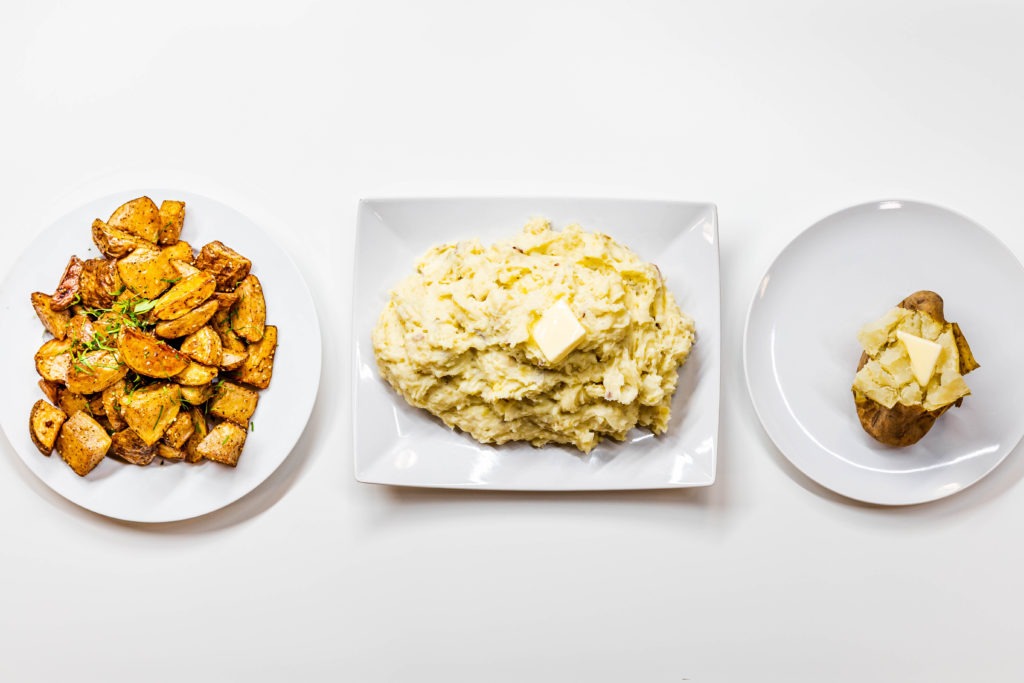

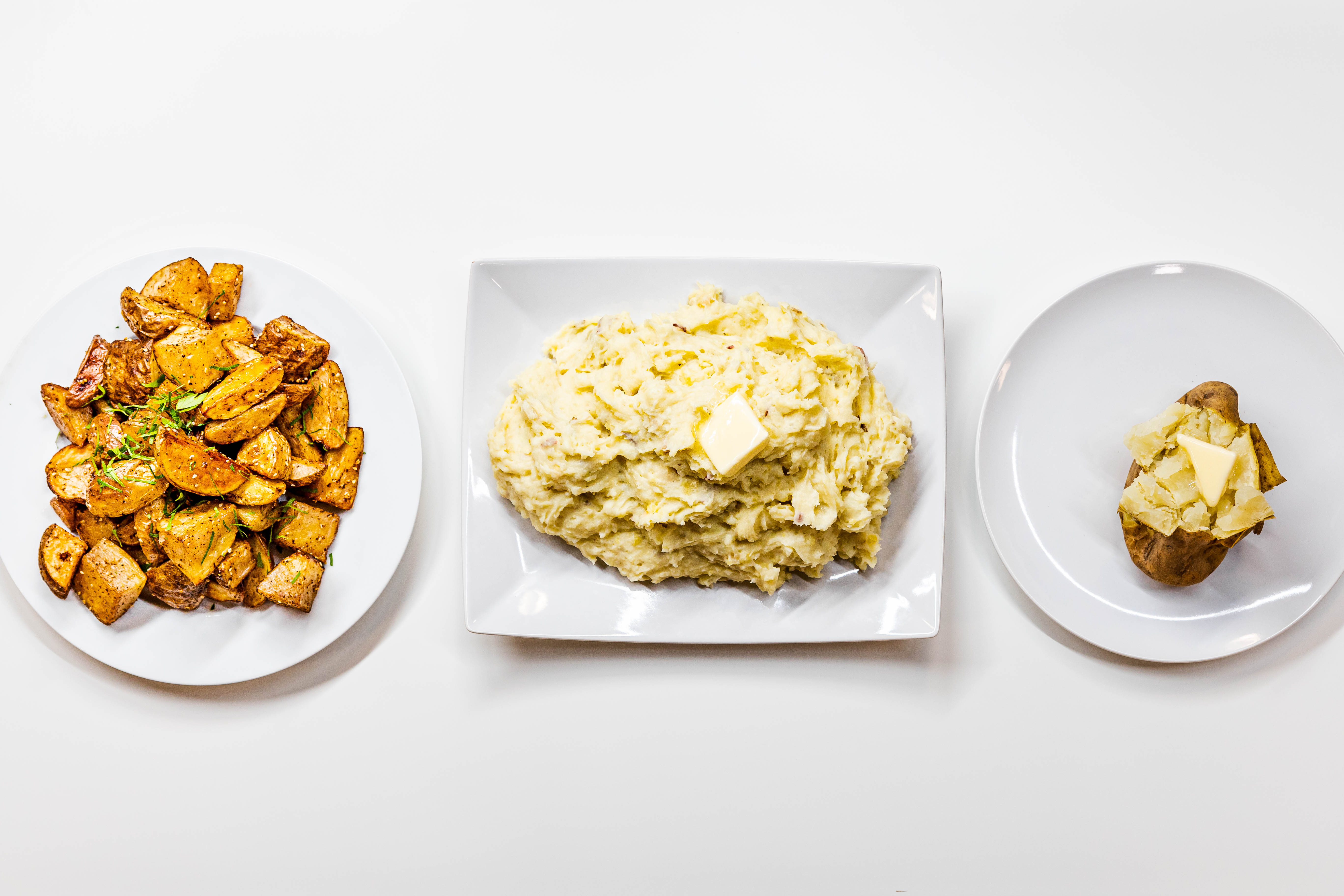

There are two main divisions within the potato kingdom: mealy vs waxy potatoes. Mealy potatoes, which cook up with a “drier” texture that is more finely textured, concentrate more dry starches in their cells. This also makes them quite dense. Because of their drier, fluffier cooked texture, they are excellent for making fries, baked potatoes, and mashed potatoes. They can absorb cream and butter more readily, making the finished mash rich and luscious. The cells in these potatoes tend to break apart more readily, practically disintegrating in boiled dishes if not treated properly. This tendency to disintegrate makes mealy potatoes a less-than-ideal choice for some casseroles and gratins.

Waxy types, however, carry less starch and cook up with a “wetter” texture. Their lower starch-content also means that they hold their shape better—there are fewer starch granules that will burst and expand, throwing cell pieces hither and yon. They are ideal for the gratins and casseroles but cook up as soggy fries and heavy mashed potatoes. Still, they are some of my favorites for many applications.

Potato doneness temperatures

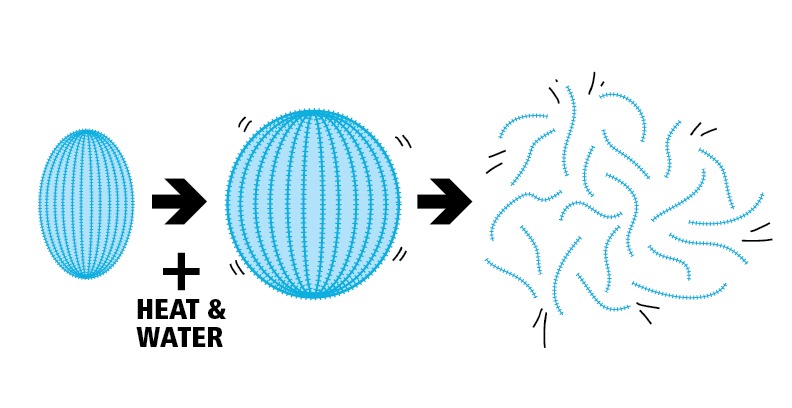

Whether you use waxy potatoes or mealy, the physical changes that need to happen are the same: starch granules need to swell and burst, a process which happens beginning at 137–150°F (58–66°C). But that’s only where it starts. To soften the starches and improve the texture, you really want to get as close to water’s boiling point as you can.

Think of when you add starch to a sauce. The sauce stays thin until you approach the boil, and only then does the sauce thicken. That’s because of the starch gelation at that point. We want the same thing in our potatoes, but instead of getting thicker, the potato flesh gets softer, less chalky, and far more appetizing. The closer you can get your potatoes to the boiling point, the better.

To test this idea, we cooked several potatoes in our demo kitchen and studied the results. We used yellow, red, russet, and sweet potatoes and inserted probes into the center of each one. We boiled two of each kind and baked two of each kind, setting the corresponding ChefAlarms for 190°F (88°C) and 210°F (99°C) (based on the advice of some potato experts we contacted). It was only after setting the high alarms and bringing our water to a boil that we realized a problem: we can’t boil water up to 210°F (99°C) at this elevation! Our water boils at about 204°F (96°C) up here in the Mountain West, so there’s no hope of boiling a potato to 210°F (99°C)!

We adjusted our goals, aiming for 202°F (94°C), the same distance below the sea-level boil as the suggested temperature.

Why not just set the target for the boiling point itself? Thermodynamics. The closer the temperature of an object gets to the ambient temperature, the longer it takes to heat up. Heat exchange slows down drastically. So cooking all the way to the boiling point tacks on significant time. Plus, starch gelation is an endothermic process, so the potatoes are actually sucking heat out of the probes as the starches loosen and abandon their crystalline state. Actually reaching the boiling point is not easy.

Baked potato doneness temperatures

What about the baked potatoes? Hot ovens can go well past the boiling point of water, no matter where you are, right? Right, but baking potatoes past the boiling temperature only achieves one thing: it actually boils the water out of the potato leaving you with a denser, less fluffy, less appetizing potato to eat. Baked potatoes taste best when baked up near the boiling point of water, just like boiled potatoes—which makes it easy to remember.

Below, you can see the results from our testing. The potatoes cooked to 202°F (94°C) were significantly lighter, fluffier, and more tender than those pulled at 190°F (88°C).

Potatoes are best cooked by reaching a point 2°F (1°C) below your local boiling point. This is especially useful for baking and roasting potatoes. When you put your potatoes in to bake at 375–425°F (191–218°C), insert the probe from a ChefAlarm into the largest potato or potato chunk and set the high-temp alarm for 2°F (1°C) lower than the boiling point of water where you are. You’ll know exactly when your potatoes are finished cooking and you won’t risk undercooking them in the pot, or overcooking them in the oven.

A cool thermal trick for boiling potatoes

If you want your potatoes to hold their structure better—so they don’t fall apart as easily—Harold McGee has a tip.

If preheated to 130–140°F/55–60°C for 20–30 minutes, [potatoes] develop a persistent firmness that survives prolonged final cooking. [Potatoes] are usually started in cold water, so that the outer regions will firm up during the slow temperature rise. Firm-able vegetables and fruits [like potatoes] have an enzyme in their cell walls that becomes active at around 120°F/50°C (and inactive above 160°F/70°C), and alters the cell wall pectins so that they’re more easily cross-linked by calcium ions. At the same time, calcium ions are being released as the cell contents leak through damaged membranes, and they cross-link the pectin so that it will be much more resistant to removal or breakdown at boiling temperatures.”

Harold McGee, On Food and Cooking, pg 283

For potatoes that hold their shape, put them in the water (or other liquid) while it is cold and bring them up to temp with the water. No more mushy potato cubes in your soup!

How to roast sweet potatoes for maximum sweetness

First, we need to clear something up. Sweet potatoes are not yams. Not even the gnarly looking orange ones. Yams are a long white tuber from Africa and Asia that is in no way related to sweet potatoes. Your family may call the sweet tubers you eat “yams,” but they are just sweet potatoes.

Though they belong to a separate genus from “regular” potatoes, sweet potatoes warrant a mention here. Like potatoes, sweet potatoes are also filled with hard starches. In fact, they are much harder to cut raw than potatoes. But! They also have an enzyme in their cells that turns those starches into maltose—a sugar composed of two glucose molecules that tastes about a third as sweet as table sugar. Some breeds of sweet potato will turn as much as 75% of their starch into maltose if given the chance!

To take advantage of this sweetening enzyme, your potatoes need to spend time in the enzyme activity zone, from 135–170°F (57–75°C). The longer your sweet potatoes sit in this zone, the sweeter they will be.

With some planning, you could place them in a warm oven for a half-hour or so before cooking, then bring the oven up to temp with the tubers inside. Doing so will give the enzymes more time to work and sweeten the potatoes. Their optimal doneness temperature is the same as that for standard potatoes—two degrees below the boiling point of water where you live.

With Holiday dinners upon us, a deeper understanding of how potatoes work is essential for nailing the details of your next big meal. With a ChefAlarm you can bake your potatoes to perfect, fluffy doneness and with a Thermapen® you can know when your roasted potatoes are cooked through and ready to serve.

Temperature is everything, even for the potato half of “meat and potatoes”!

Shop now for products used in this post:

> To soften the starches and improve the texture, you really want to get as close to water’s boiling point as you can

One thing that wasn’t clear here is if you want the starch in the potato to get to as close to 210*F as possible, or if you need to get it as close to boiling as possible. The article felt like it was on pretty solid scientific ground up until this point.

If you’re trying to heat the starch to as close to 210*F as possible, then the recommendation of 2* below boiling for your altitude doesn’t make science sense (thought it might make practical sense). In other words, I can’t tell if this is a practical or scientific recommendation.

—

As a fellow Utah resident, I’d be interested in hearing about the possibility of using a pressure cooker or Instapot to hit those higher temperatures – especially if getting closer to 210 is the real ideal.

Michael,

You want to get the temp as high as you can without drying out the potato. If you bake taters until they get above local boiling point, they’ll start getting dry. So just try to get close to YOUR boiling point as you can.

A pressure cooker is a great idea to get the temp higher! Sadly, there is no way to know what the internal temp is IN a pressure cooker. But it should, in theory, work.

Is there a list that delineates which potato variety is mealy versus which is waxy?

Thank you for your articles. They are always interesting.

Basically, russets and purples are mealy and reds and yellows are waxy. In the USA we don’t have lots of varieties available, and your grocery store will usually just have 2–4. Usually, a russet that is mealy and one or two waxies.

This is remarkably good information and has made some great baked potatoes. Just to clarify, my elevation (892 feet above sea level, so my local boiling point is 210 degree F. The goal is to bake the potatoes 2 degrees less than my local boiling point (210 – 2 = 208 degrees F). The potatoes are perfect.

It is true that sticking a fork or sharp knife can also test doneness, but my problem has often been the OVERcooking of my potatoes. They’re too dry, the skin is hard as a rock, the center sometimes becomes hollow (water dried up, I guess), and it’s just not fluffy and flavorful. Measuring doneness by temperature makes it easy. I love it.

Wonderful! So glad we could help make your food better!

There is another cooking methodology that throws a different sort of curve ball. Sous Vide cooking. Where traditional cooking is more toward a heat source temp is higher than the desired internal food object target temp, the Sous Vide has the heat source set at the exact desired internal temp where the food object internal will never exceed the target temp.

Now the variables change more toward time of holding the temp at the desired internal temp. In reading chefs that have a lot of experience and my own experience, cooking potatoes will defiantly have different results for different temps, such as 185, 190, 195 (as water temp verified by Thermapen One) as well as duration of the held temperature at those setpoints to achieve the desired breakdown/tenderizing. It is an interesting method of cooking and highly recommend trying it. One of the interesting element is flavor of the food object has more flavor as nothing leaves the bag to the water. That as well as the spices, fats, etc that stay in the food.

The cool trick for boiling potatoes

After holding at 130-140, do you continue cooking to 2 degree below boiling?

Yes!

Great info! Thanks everyone for contributing. I will try these methods out!