Tasso Ham at Home: How to Cure and Cook to Temp

Have you ever had tasso ham? If so, you almost certainly love it and need to read what we have to say. If not, then you should definitely keep reading, because you need to acquaint yourself with this amazing food.

Tasso ham is a classic ingredient from Cajun cookery that adds spice and flavor to gumbos, beans, greens, and just about anything that is simmered or boiled.

Unless you live within easy driving distance of the Gulf Coast, chances are that you don’t see tasso for sale very often. Sure, you can buy fancy-pants gourmet versions of it at upscale markets, but in many ways, that seems to betray the frugal, down-home tradition from which this ingredient springs. More appropriate than buying “gourmet” tasso would be to make your own.

Here, we’ll show you how to make amazing tasso in your own kitchen—including some surprising temperatures you should know about—so that you can get some real cajun flavor into your cooking.

What is tasso ham?

First, it seems necessary to point out that tasso ham is not, technically, even ham. “Ham” refers to a particular cut of pork—namely the hind leg—while tasso ham is made from cured slabs of pork shoulder.

But this is a distinction without a difference, much like insisting that a cucumber is a fruit, not a vegetable.

Ok, so it isn’t (but is) ham. What is it? Tasso is a traditional part of Cajun cooking in Southern Louisiana and the regions round about, where it is made by home cooks as well as local butchers and grocers. It is made of quick-cured slices of pork shoulder (more on that below) that are seasoned with a mix of thyme, marjoram, allspice, pepper, and, of course, cayenne pepper. These seasonings are applied without any pretense of refinement. Tasso is full-flavored, high-voltage food that came here to work, not stand around, and the amount and intensity of the seasoning reflects that.

(Incidentally, to make it, slice the shoulder with the grain—about an inch thick. In a steak, or another cut of meat, slicing with the grain would make for stringy, tough meat, but for tasso that doesn’t matter. This cutting method will actually help it hold together better during cooking.)

Once cured and seasoned, the tasso is smoked slowly to flavor it and cook it enough to keep well.

When you use tasso, the slabs of ham are often diced and added to stews and soups where they act, not as the main meat “star,” but as a hearty, rich flavoring agent. They can even be crisped up in a hot skillet before adding them to your dish, much like you would treat bacon.

How to cure tasso ham

Tasso is cured quickly, which means that we use a quick-curing salt. Prague powder #1, the standard cure for things like this, is a combination of sodium nitrite, salt, and pink color (to delineate it from regular salt). The sodium nitrite is what does the curing, changing the structure of the meat and creating an environment that is hostile to bacteria, especially those that cause botulism.

Those nitrites also give cured meats that characteristic cured-meat flavor and pink color. The color, incidentally, doesn’t come from the pink dye in the salt, but from the interaction of the nitrite salt with the meat proteins themselves.

Note though, that curing salt can be dangerous if you use too much of it. Be sure to weigh your cure carefully. You want enough cure, but by no means do you want too much.

Tasso is cured using the “salt box” method. The thinnish slabs of meat are dredged directly in the cure—a mixture of salt, sugar, and the curing salt—and laid on a sheet tray in the fridge for just a few hours to cure. This direct application of the cure works very quickly and is easier to manage in your fridge than using a bucket of brine for 3–5 days.

Tasso temps: why so low?

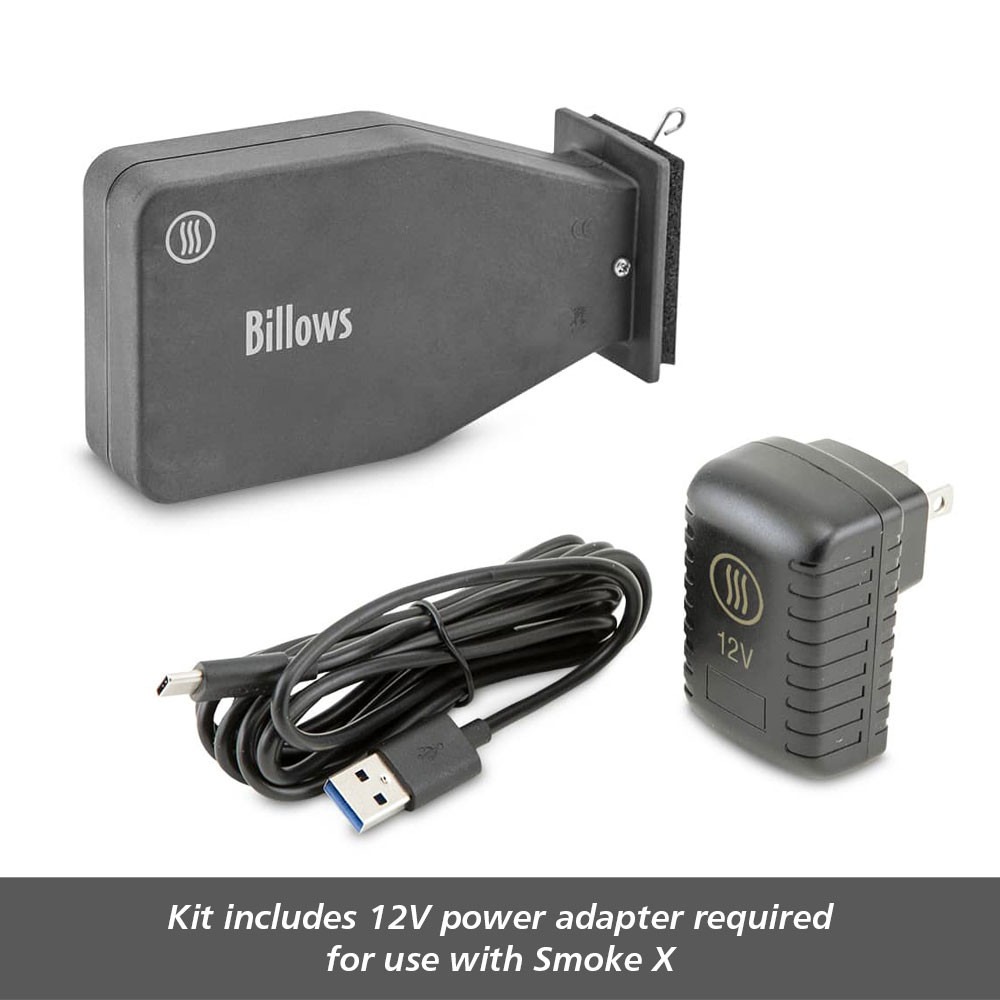

For tasso, we want a deep, richly smoky flavor, and that means smoking it at a lower temperature. We used Billows™ BBQ Control Fan to keep our smoker at an even 225°F (107°C) throughout our cook and the ham came out absolutely delicious. But the smoking temp is not the only low temp we’re going to encounter here.

When we smoke tasso ham, we only cook it up to 150°F (66°C). Why is that? After all, this comes from the shoulder, and we all know that pork shoulder reaches optimal shreddy goodness at about 203°F (95°C). But therein lies the rub, as it were. You’re not going to have a sandwich full of tasso. In fact, though you may snack on a cube while prepping a stew, you generally won’t eat tasso by itself. It is used as a flavoring meat, an ingredient in other things to give them salt and spice and porky goodness—we don’t need it to be mega-tender, per se. Cooking it to a mere 150°F (66°C) is faster, still gives it time to smoke, and produces a ham that turns out wonderfully.

To prevent overcooking, be sure to use a leave-in probe thermometer like Smoke X2™, and also verify the temperature before you take it out of the smoker with a fast and accurate thermometer like Thermapen® ONE. Do that, and you’ll end up with just the right texture.

Tasso ham: very country, very farmhouse, very easy

Tasso is a very “country” ingredient and is about as far from refined as a ham can be—and its production reflects that. It is far from difficult to make. It would be no problem to assign a farmhand to go make the tasso during hog-killing season, and I suspect that’s really how it evolved. Cut it, dredge it, rinse it, season it, and smoke it. No changing of salts, no rotating hams, no hanging for three months—this is curing meat at its most basic, almost primal level.

I hope you’ll try this amazing and easy recipe. It’ll make your next cook that much tastier, and with our temperature advice and tools, it’ll turn out perfectly every time.

Homemade Tasso Ham Recipe

Description

Homemade tasso ham recipe, for use in gumbo, beans, stews, soups, etc.

Ingredients

For the meat and cure:

- 5 lb pork butt, boneless (you can debone it yourself or buy it boneless)

- 8 oz kosher salt

- 4 oz brown sugar

- 10 grams pink curing salt (Prague powder #1)

For the seasoning:

- 1/4 C cayenne pepper (you can use less if you want, but I like it this hot)

- 1/4 C black pepper, medium grind

- 2 Tbsp dried marjoram

- 1 Tbsp ground allspice

- 1 Tbsp dry mustard

- 2 Tbsp granulated garlic

- 2 tsp celery seed

- 2 Tbsp dried thyme

Instructions

Brine the meat

- Slice the pork butt with the grain into steaks about 1-inch thick.

- Combine the sugar, salt, and curing salt in a bowl. Make sure everything is very evenly distributed.

- Dredge each piece of pork in the curing mixture on all sides.

- Place the cure-covered pork on a rimmed sheet tray and refrigerate to cure for 4–5 hours, uncovered.

Season and smoke the ham

- Using your preferred smoking wood and Billows BBQ Control Fan, preheat your smoker to 225°F (107°C).

- Take the pork from the fridge and rinse it under cool running water.

- In a medium bowl, mix together the seasoning ingredients. Do not add any salt, the meat has absorbed enough.

- Liberally coat the pork in the seasoning mixture.

- Place the pork in the smoker and insert a probe attached to your Smoke X2. Set the high-temp alarm on the meat channel for 150°F (66°C).

- Close the smoker and smoke the meat!

- When the high-temp alarm sounds, verify the temps with your Thermapen and remove the tasso from the smoker.

- You can cut the tasso up immediately and toss it into a pot of beans or gumbo, but with this much, you’ll have plenty to store. Wrap it tightly or vacuum seal it and freeze it until needed.

Shop now for products used in this post:

Yes, it is technically, botanically a fruit, but we use it as a veg anyhow.↩

It is very chic right now to have “uncured” hams and sausages. But even those that claim to be uncured are usually made “without nitrates or nitrites except for those found naturally occurring in celery juice and sea salt,” a phrase that exploits a labeling loophole. If the ham or salami is pink, there were enough nitrates in there to turn it pink, no matter where they came from.↩

Yes, it is technically, botanically a fruit, but we use it as a veg anyhow.↩

It is very chic right now to have “uncured” hams and sausages. But even those that claim to be uncured are usually made “without nitrates or nitrites except for those found naturally occurring in celery juice and sea salt,” a phrase that exploits a labeling loophole. If the ham or salami is pink, there were enough nitrates in there to turn it pink, no matter where they came from.↩

Looks great. Thanks for sharing. I live in Charlotte and have had tasso ham in various meals, including shrimp and grits. BTW, where did you find such a wonderful pork shoulder? That is the nicest piece of shoulder I’ve ever seen. Thanks

I need to try in in shrimp and grits—it would be amazing there. I got that shoulder at a local grocer that happens to have a very good meat department, and it really was a fine piece of meat.

While the endpoint temp is what matters, it would still help to include some sense of the smoking time. Is it just a few hours, or are we talking overnight? If I put it on at 5pm, am I going to be babysitting it until midnight? Otherwise, a nice recipe for an underutilized ingredient!

Good question Ted. It only takes few hours, if that. You could easily get this cured and smoked before lunch on Saturday.

I am 62 years old and have lived in cajun country all my life. This is a great recipe for TASSO.

I have never seen it referred to tasso ham sold where I live. It has always been simply called “TASSO”.

Thank you, sir! And I’m glad to know how it is referred to in Cajun country. Thank you for the info!

in an omelet? on pizza? any other ideas besides beans?

I hadn’t thought of an omelet, but now I want one very badly! Green beans, collards, pizza (chopped very finely), sliced thin and crisped and put on a burger in place of bacon…all great ideas. Once you taste it you’ll start to know where else it could be used.

Put into home made mac n cheese to give it a kick, and I’ve done a lasso and crawsish tail fettuccine with a Cajun Alfredo.

I’ve smoked hundreds of shoulder and never, ever seen one that looked even close to that. Hard to tell from the picture how its oriented with respect to the clavicle and the money muscle. It actually looks more like a collar than any shoulder I’ve seen, but if I ever come across anything close I’ll try the recipe….it sounds good. I wouldn’t go to the trouble just to use it for “seasoning”. My Signals awaits the dream shoulder 🙂

I’m also not sure how this was oriented. If it was from the collar, then I want more collar!

For the cure, are the salt and brown sugar measurements by volume or weight?

By weight.

If the meat is preserved and smoked, why does it need to be stored in freezer. Is it just not dried out enough like a summer sausage would be?

Dr Jones,

That’s a good question, and one to which I’ve given a good deal of thought. There are a number of factors at play here, and I think your summer sausage comment is right on track.

First, I want to take a look at summer sausage itself, as an example of something that doesn’t need refrigeration. Summer sausage does everything to stay shelf-stable. First, it is a fermented sausage, which means it will have a very low pH—an environment unfriendly to micro-beasts. Next, it is tightly wrapped, essentially hermetically sealed. No bacteria are getting in and making themselves at home, at least until you slice into it, at which point it does need to be refrigerated. Of course, it is highly salted, creating a lower water activity, and it is also cooked after it is formed and packed. All those factors together make it pretty dang stable.

Tasso is cooked, so it checks one of those boxes. But it is not fermented, so its pH could be a problem if it were kept at room temp and sealed. Botulism-causing bacteria thrive in environments that are both high pH and low oxygen. So botulism is a risk in a sealed system without acid, but not in an open system with access to oxygen. Ok. So we can’t vac-seal our tasso and leave it out. Why not just leave it out?

Here we hit the salting. There are other shelf-stable meats and sausages. Think of Spanish jamon hanging from the ceilings of bars throughout Iberia or of (again) Spanish chorizo, or of German Landjäger sausages. What these all have in common is the degree to which they are salted and/or dried. Two related things happen here. One is the bare absence of water. Bacteria need it to thrive, so the drier the meat, the more stable. But beyond the absence of water is the presence of salt. The concentration of salt in those meats means that any bacteria that get involved will experience tremendous osmotic pressure that will suck their water out and kill them.

Tasso is well salted, but I think the degree to which it is dried means that there is enough water activity to not completely eliminate the risk.

Finally, there is the cultural aspect. I can’t back this up with anything other than supposition, but I imagine that when it came to cured/smoked meats in the past, people living in pre-refrigeration times were used to their cured meats being drier (and possibly saltier) than we like them now. Perhaps they had a chunk of tasso that they left on the counter, but it dried up and got crusty on the edges, and that was just part of what having tasso was like. You’d stew it and it wouldn’t matter that it had been all dried weird. Our modern sensibility for cured meats is much less necessity-driven. Again, that’s personal theory.

I don’t know if this has been helpful. I’m tempted to make a batch and try salting it longer so that more liquid gets pulled out. I’m also tempted to attempt other preservation techniques, especially confit, to get a shelf-stable tasso—or even finding a way to introduce acid to the cure, then smoking it, then vacuum -sealing it, then sous-vide cooking it—make summer sausage out of it.

Is any of that helpful? I hope so. Feel free to ask any follow-up questions!

with respect to refrigerating and freezing the completed tasso: it’s possible to salt cure pork shoulder and dry cure it so that it will keep indefinitely without refrigeration. as you say, though, we generally don’t want it that dry.

if someone wants to try doing it, check a recipe for lonzino–Italian cured pork loin. for salt cure my recipe uses .5% Insta Cure #2, 3.5% Kosher salt, and 2.5% sugar–all percents by weight of trimmed meat. naturally, the seasoning for tasso would be different than what lonzino uses. the meat is cured in the salt and seasonings (i wait until just before smoking to apply most of the tasso seasoning) for 1 week per inch of meat thickness. for tasso, cutting the pork shoulder apart to get rid of the really tough cartilage will yield pieces that are generally 1.5 inches to 2 inches thick. i cure my tasso for about 7 days in a brine cure, but a week would do the small pieces if the cure is applied to all sides of the meat with a rub.

anyway, after curing, you’d normally smoke as for normal tasso. but the Insta Cure #2 releases nitrite slowly over time–therefore, when using it you need to hang and air cure the meat. when i make long cure pancetta and Calabrian pancetta, i let the meat hang for a month so that it loses about 30% of its trimmed meat weight. with the smaller diameter pieces you will have for tasso, i would guess that 2 weeks would be fine, so long as the finish weight is at least 75% of the trimmed meat weight.

yes, that’s a lot of work. lonzino is worth it. not sure tasso would be. the more moist yet still concentrated, smoky results of a shorter cure followed by smoking are fantastic. and we have refrigeration to compensate for not completing a process that would have kept botulism at bay 150 or more years ago.

Larry,

Thank you so much for sharing your expertise on this matter! The Lonzino sounds delicious, and I may have to give it a try this spring. We’ll see if I can fit it into my home curing schedule.

Do you even need quick cure? Heavily salted for 4 hours, rinse, spice, into the smoker. How would this differ from regular Q if you are use immediately or freeze?

Ready for shrimp and grits!

The quick cure changes the protein structure and gives it that classic cured flavor. You don’t need it, but it tastes more like tasso if you use it.

I live in Michigan and Tasso is impossible to find here in Yankee territory. It is an amazing ingredient in jambalaya (I recommend the Poorman’s Jambalaya recipe by the late great Paul Proudhomme). I bought a smoker primarily to make tasso, tho I can’t wait to try so many other things. One question, as I’m new to smoking: does this recipe need water in the water pan? I’m using an electric Masterbuilt smoker. many thanks for this recipe!

Raymond, you shouldn’t need water in the pan. I didn’t use any! I hope you enjoy your homemade tasso as much as I enjoy mine!

If you don’t have pink curing salt, is there a substitution for it?

Not really, no. You could soak it in celery juice—which is high in natural nitrates (or nitrites?)—that will go partway there, but it will also taste…like celery.

Made this last time with pork shoulder. Came out fantastic. Smoking some now made with pork tenderloin. Can’t wait to see how it comes out. I’m guessing that the pork tenderloin with less fat should make for a very lean Tasso.

Yes, it would. I like it best with the fat from the shoulder.

Well it came out fantastic. Seasoned to perfection. Yes, and a little on the lean side obviously. Still made a heck of a pot of red beans.

Thanks for publishing the recipe will use it again

Hey, that’s great! I’m so glad!

Great recipe. I used it on a pork loin, and it came out fantastically. Mind you, I’m Cajun, so I may have eaten a bite or two of tasso in my lifetime, comme sa. I just got very, very tired of paying sky-high prices for ready-made tasso, and since my husband just got a new smoker, I figured I’d try my hand. After all, my ancestors made this stuff for centuries. It’s in my genes.

Note that you can also do an overnight soak in regular salt, but the end result is…Well, salty, and the meat doesn’t keep nearly as well frozen or refrigerated. Otherwise, in order to adequately preserve the meat, the smoking would have to go far, far beyond what’s prescribed here. Tasso in its most basic Cajun form is smoked for several days in a shed smokehouse, and it is labor-intensive to produce.

Also need to note that tasso, like many other things in Cajun cuisine, came about out of a combination of Nova Scotian/peasant French recipes and having to adapt foreign ingredients to those recipes. We are a thrifty people. My grandmother used to say that when we butcher a hog, we use everything except the squeal, and that’s only because we can’t shove it into a pot with some Tony’s.

Wonderful! I’m glad a real Cajun approves!

This was incredibly yummy, though I cut the cayenne and pepper way back to 1 tablespoonful and it was still way too hot for me. Wondered if I was supposed to brush off the spices on the surface before using the tasso? That would reduce the heat, I think. Made great jambalaya, though.

I’t supposed to be spicy, but one advantage of making it at home is that you can adjust it to your exact preference. Don’t brush the spices off, but feel free to keep cutting the cayenne. Enjoy the jambalaya!

I recently ate breakfast at an out-of-the-way cafe in Ft. Worth and had Cajun Eggs Benedict. They served 3-4” corn cakes topped with tasso, a poached egg, and Hollandaise Sauce.

The tasso, sliced about 3/8” thick, appeared to have been tossed on the flat top and grilled. Now I’m searching for a way to do replicate it at home.

This looks like a great place to start for the tasso. Thanks!

You are welcome. It is always a joy to find inspiration at new restaurants and try to recreate that experience at home.