Through the Temperature Danger Zone: On Cooling and Heating for Food Safety

You’ve worked and sweated all day at the stove making a perfect chicken soup for the coming weekend. But after all that work, will your soup be safe to eat tomorrow? It doesn’t occur to most home cooks that once their food is cooked, the battle against foodborne illness is only half fought.

Most of the attention on food safety is given to the pre-cooking stage of preparation, i.e. not leaving chicken on the counter for several hours before cooking it. But the temperature danger zone (TDZ) works in both directions: You must get food up to temp quickly, yes, but you must also get food down to temp quickly.

In this post, we’ll explore the food safety guidelines used by the pros to keep foods safe so you can protect your family and friends.

Temperature danger zone

The USDA calls the range between 40°F and 140°F (4°C and 60°C) the “Temperature Danger Zone” (TDZ). They call it that because it is the range in which bacteria are most able to multiply quickly.

What do we mean by “multiply quickly?”

We mean doubling in as little as 20 minutes. If that doesn’t sound super fast to you, consider this: If you have just 150 bacteria floating on a soup, in 20 minutes it’ll be 300, 20 more minutes means 600. At this rate, you will have enough Salmonella bacteria to cause a serious infection (~100,000) in just over 3 hours. If you start with 1,000 bacteria, you get there in under 2 hours and 15 minutes. This is exponential growth, and it adds up very quickly.

Because bacterial metabolism is linked to temperature, however, you can prevent this kind of bacterial build-up by controlling the temperature of your food. The safe zones are below 40°F (4°C)—temperatures too cold for most bacteria to reproduce— and above 140°F (60°C), temperatures that begin to be lethal to bacteria.

Guidelines, problems, and solutions

So what does this mean for the home cook? And when we say we must get the food down to temp “quickly,” what does that mean?

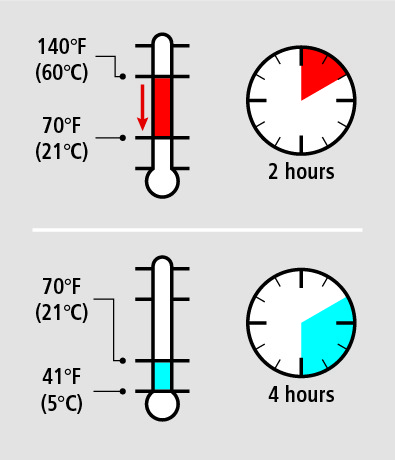

The guidelines for ServSafe—a nationally recognized food safety training program—state that you must cross the entire TDZ within 6 hours after cooking, getting from 140°F (60°C) down to 70°F (21°C) within 2 hours, then crossing from 70°F (21°C) down to 40°F (6°C) within another 4 hours. These time/temperature guidelines work both for heating (cooking or reheating) and for cooling.

So what does this mean for you? It means that that big pot of chicken soup you just made cannot go straight into the fridge from the stove. A gallon (or more) of thick liquid will take far longer than 6 hours to cool in a refrigerator, so we need to assist it. (Not to mention the fact that such a large pot of hot food will act as a space heater in the fridge all night, putting all the other foods in the fridge at risk!)

In professional kitchens, large pots of liquids are often cooled using ice wands. These plastic wands filled with water are frozen and used to stir the pots, cooling the contents from the inside. And while you can buy small ice wands at your local restaurant supply store, most people probably don’t have them available at home. I certainly don’t. And ice wands are really only good for liquids, not for a big pot of rice you want to use for tomorrow’s stir-fry or the extra pulled pork from today’s cookout, for example.

An easier way to cool cooked foods quickly at home is to increase the surface area of your food—spread it our as much as you can! If you have cooked a pot of rice, spread it out on a cookie sheet or two so that it has lots of space from which to vent the heat.

If you’ve cooked soup or stock, you can pour it into shallow vessels like cake pans for the initial cooling. The first stage of cooling—140°F (60°C) down to 70°F (21°C)—can mostly be accomplished on a countertop if the food is spread sufficiently thin. Stir or otherwise turn the food from time to time to help it cool more quickly. Stirring releases energy from foods and can help them cool.

Let your rice/soup/roast come to room temperature within two hours. Be sure to check the temperature occasionally with a Thermapen®, or track it throughout with a ChefAlarm® or DOT® set to sound at a low-temp of 70°F (21°C). (The ChefAlarm also has a built-in timer that you can set for 2 hours—handy!)

Once you achieve room-temp (within 2 hours!) you can put the food in the refrigerator without fear of heating everything else up. If you have a big enough batch, you’ll want to continue monitoring the cooling food or spot-checking it over the next few hours to make sure you arrive at 40°F (6°C) within another 4 hours.

Remember that food is only as safe as its least safe part! Proper temping means checking the thermal center of the food, where it will be hottest if you are cooling, or coldest if you are heating.

A word about infrareds. You may be tempted by the convenience of an IR gun in spot-checking cooling food, but you have to be very careful if you are using an infrared thermometer. IR thermometers only measure surface temperatures, which means that you aren’t measuring the thermal center. If you are cooling a liquid, stirring it and then pointing the IR at it will give you a good result, just don’t measure the surface!

How long can cooked food be safely held at room temperature?

Cooked foods can be held at room temperature for two hours—just like in the cooling process. Room-temp leftovers older than 2 hours should be thrown out. If you’re having a picnic or barbecues outside in temperatures above 90°F (32°C), safely store leftovers within 1 hour to prevent bacterial contamination.

Why such drastic measures? If food sits out for too long, can’t we just re-heat it to kill the bacteria that has grown? Not according to Dr. Karin Allen and Dr. Jeff Broadbent, Professors of food safety and quality at Utah State University. They say the real danger is not bacteria that cause sickness in this case, but bacteria that actually produce toxins on the surface of the food. E. coli can be killed and won’t hurt you anymore, but Bacillus cereus, for instance, actually produces a toxin that stays on the food after the bacteria are killed. There are some other bacteria that do the same thing, Clostridium perfringens, and Staphylococcus aureus being chief among them, and these bacteria are the reason that you have two hours to get your food in the refrigerator or throw it out.

Reheating leftover food

When you reheat any leftovers, remember that the magic number is 165°F (74°C). Not only is that the temperature to instantly kill most bacteria, but more importantly, it is the temperature at which most bacterially-created toxins that we mentioned above will be destroyed.

Food safety requires that all leftovers be reheated to 165°F for at least 15 seconds. Reheat all foods rapidly. The total time the temperature of the food is between 41°F and 165°F should not exceed two hours.

Food that has been reheated should be served immediately! Reheat only what you plan on eating, because re-cooling leftovers after they’ve been reheated is not recommended. (not only from a safety standpoint but from a food-quality standpoint, too!)

Conclusion

Even using the best food safety methods in your food preparation cannot always protect you from foodborne illness. If you don’t cool or reheat your food properly, you risk infection caused by bacteria breeding in the temperature danger zone—between 40°F and 140°F (4°C and 60°C). Cool your food quickly and completely to avoid these problems, and use a quality thermometer to verify that you’ve achieved safe temperature levels.

For more on food safety, see our post on the Temperature Danger Zone.

good site

In the case of a cut meat (not ground) like pork chop, steak, ribs isn’t it the surface where the bacteria proliferate? Like smoking at low temps like smoker that drops below 200F for a 30 minutes and the cook continues. Is there a danger there?

It should be ok if there are no places where the outside could have gotten inside.