How to Cook Pasta, Better

If there is a food that is more versatile than pasta, I’m not sure what it is. The sheer taxonomy of it alone boggles the mind. Fresh and dried, filled and unfilled, extruded or rolled, hollow or solid—those are just the forms. Then there are the preparations—tomato sauces of a million varieties, pesto, cream sauces. And yet, despite—or perhaps because of—that ubiquity, pasta is constantly simmered in myth and folklore. In this article we intend to dispel some of those myths, and to tell you how to use actual tools, rather than folklore, to achieve perfect pasta.

Contents:

- Pasta history and background

- Pasta science

- Difficulties of pasta cookery

- How to cook pasta

- Pasta al pomodoro recipe

Pasta history and background

Pasta was not introduced to Italy from China by Marco Polo in the 13th century. Both written records and archaeological evidence suggest that Italians made pasta from wheat or its relatives centuries before that time. While Polo may have brought some noodles back with him from his journeys, by no means was he the means of their introduction to the people at large.

Pastas in various forms may go back as far as the 4th century B.C, but because these “edible pastes”(a literal translation of what some pastas were called in Italy for a long time) were the food of the common people, there is little record of them.

In America, we most often associate pasta with spaghetti, though that is a particular shape of pasta. And we also mostly associate it with tomato sauces, though those are a relatively recent addition to the Italian menu canon. In fact, the first recorded recipe for a tomato sauce for pasta comes from an 1839 Italian cookbook, Cucina teorico pratica, by Ippolito Cavalcanti.

The root of Pasta’s popularity in the States stems primarily from the vast migration of Italians, especially from Naples, to the USA in the late 1800’s. They brought with them an appetite for pasta that was, for the most part, served by import for decades. But due to interrupted supplies of pasta imports during the First World War, pasta production became a real thing in America in the 1910s and 20s. To produce the pasta, farmers in the Dakotas began growing durum wheat to meet the demand. In fact, to this day most of the wheat grown for pasta, even in Italy, is grown in the American Midwest.

Durum wheat is important because it is exceptionally high in protein (gluten), which gives the pasta the structure it needs to dry and reconstitute effectively. Which brings us to the science of pasta.

Science of pasta: the interplay of starch and protein

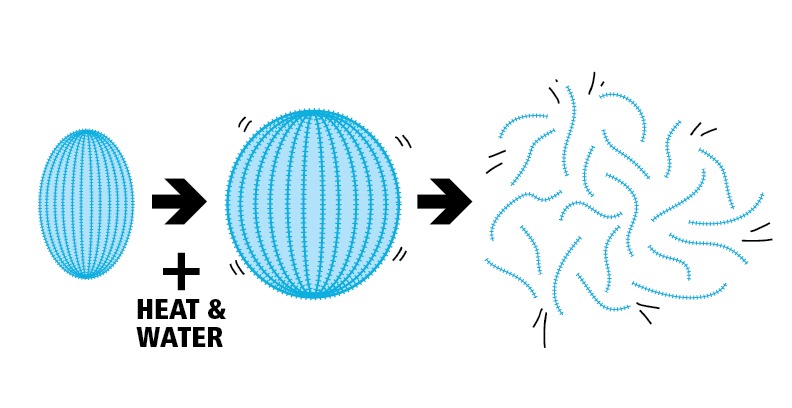

When pasta is added to boiling water, the starch granules in it start to gelatinize. These granules are tightly bound chains of sugars that swell and loosen as they absorb hot water. By all rights, they ought to swell, release from each other, and disperse into the surrounding water, and the only thing keeping them from doing so is the gluten matrix into which they are embedded. That’s why durum flour is important.

Durum semolina (small, coarse flour granules of wheat endosperm that are harder than the rest of the wheat) has a very high gluten content, and the gluten it contains is of a less elastic variety. This lack of elasticity is important for forming the pasta, as a springy dough would be hard to shape properly. But the strength of the gluten matrix holds the starch of the pasta together while it cooks.

As the water gelatinizes the starch on the surface of the pasta, deeper granules are exposed to water, and so on down. The result is an analog to temperature gradients, but with varying degrees of water absorption from the surface on down.

Cooking the pasta al dente means stopping the cooking when the center of the noodle still remains slightly underdone and offers some resistance to chewing; at this point, the noodle surface is 80-90% water, the center 40-60% (somewhat moister than freshly baked bread).”—Harold McGee, On Food and Cooking, pg. 575

Pasta will absorb “1.6–1.8 times its weight” in water by the time it is done. If not for the rigid structure of the durum proteins, the pasta would literally disintegrate. This is why you should never attempt to make pasta out of cake flour; the starch-to-protein ratio is all wrong.

Pasta problems

You would think a food with so few ingredients would be simple to prepare. But pasta’s preparation can be fraught with problems, including boil-overs and clumping. However, a little scientific thought and the right tools can help you overcome these obstacles.

Boil overs

When the pasta cooks, of course, some of the surface starches do free themselves from the noodle, which is why pasta water becomes cloudy. If your pasta water is boiling rapidly, the starches in the water can link up enough to inflate with steam and become bubbles. If those bubbles go unchecked, the water can boil over the top of your pot.

What can you do to prevent this from happening? First, use the right pot.

A low-walled pot must be filled close to the brim to accommodate both your pasta and the water in which to boil it. If you only have one inch of “headspace,” it can easily be overwhelmed with starchy foam. A taller stockpot or pasta pot is best for pasta cookery for two reasons: it allows room for the boiling water to rise without going over the top and it allows for enough water to be present to dilute the starches. If the starches in the water are more dilute, they will have a harder time forming foam structures, and the foam they do form will be weaker and easier to break up.

“It’s generally recommended that pasta be cooked in 10 or more times its weight of vigorously boiling water (around 5 quarts or liters water per pound/500 gm).”—Mcgee, pp. 575–576

Incidentally, the longer the pasta cooks, the more starch it leeches into the water. Draining the pasta as soon as it is done (see below) prevents higher concentrations of starch from entering the water. Overcooked pasta is more likely to boil over.

Another way to prevent boil-overs is to add a small glug of oil to the water. The oil breaks up the surface tension of the water, causing the bubbles to disperse. Some will argue that oil can form a slick on the surface of the noodles that will later prevent sauce adhesion, and this is a valid argument. But depending on your final preparation, that may not be a problem.

One older, tried-and-true method for preventing a boil-over is to lay a wooden spoon across the top of your pot as you cook. The spoon literally pops the bubbles as they rise, and can help prevent a boil over.

Aside from using a big enough pot with enough water, though, one of the most important ways to prevent pasta from boiling over is to never put a lid on your pasta. Here’s why:

There is a thermodynamic principle called the “ideal gas law,” that you may have forgotten about since high school physics. And it says that the pressure times the volume of a gas is proportional to the amount of the gas multiplied by its temperature and a known constant:

PV=nRT

P is pressure, V is volume, n is the number of molecules in the system, R is the ideal gas constant and T is temperature. Because of their proportional nature, if one variable on one side of the equation increases, there must be an equivalent increase in a variable on the other side. So if the temperature of a system increases without the number of molecules shrinking, then either the pressure or the volume of the system must also increase.

In a pasta water bubble, the pressure remains fairly constant—starch bubbles aren’t known for their ability to handle increased pressures. So if the temperature increases, it’s going to be the volume that increases or, more importantly, if the temperature decreases, then the volume must decrease.

We boiled two identical pots of pasta, one with the lid on, one with the lid off, tracking temperatures in and just above the surface of the water using a ChefAlarm® with optional waterproof needle probe in the water and a Thermapen® over the surface. While the water temperatures in both pots followed the same heating and cooling curves, the temperatures of the air above the water were vastly different. The lidded pasta had an air temp of 204°F (96°C)—the boiling point of water at ThermoWorks HQ (see our Boiling Point Calculator)—while the air just above the surface in the uncovered pan fluctuated between 145–163°F (63–73°C).

When steam bubbles at 204°F (96°C) met with much cooler 145–163°F (63–73°C) air, they cooled, and a decreasing T meant a correspondingly decreasing V. The cool air shrinks the bubbles. But if the steam bubbles find an environment beyond their walls that is the same as that within their walls, they can grow and build on each other without any thermal hindrance. Every time I use a lid, my pasta boils over; but if I leave the lid off, it is rarely a problem.

Clumping

Improper treatment of the noodles, especially in the first seconds of cooking, causes clumping. When the starches start to gelatinize as soon as the pasta hits the water, the surfaces can absorb all that lies between them. Noodles will have nothing left between them to lubricate them, and the starches will act as glue sticking them together. To prevent this, be sure to use enough water so that the noodles can have room, but also be sure to stir the pasta for the first minute or so in the water. This will allow water to flow evenly around the individual noodles and for gelation to begin without getting gluey. This is another reason for always adding your pasta to water that is already rapidly boiling: the active water agitates the noodles and moves them apart from each other.

How to cook pasta

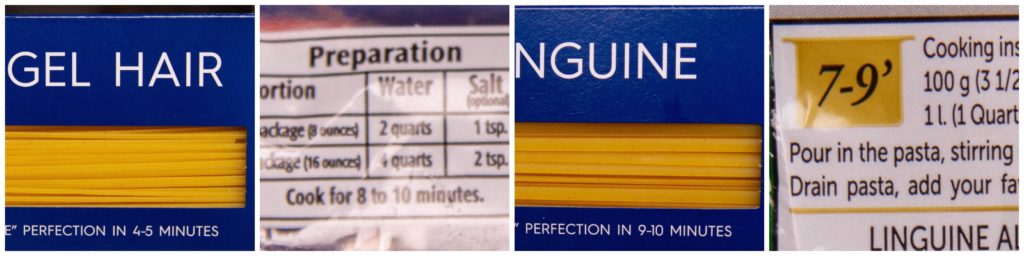

With the problems of boiling over and clumping dealt with, there’s one big question that still remains unanswered: how do you know when pasta is done? Some people say to pull a noodle out and throw it against a wall. If it sticks it’s done. But I say, hogwash. Cooking pasta is simply a matter of time. If you add pasta to boiling, salted* water, you should cook it according to the time on the package.

If that sounds like common sense to you, then you probably get great pasta results all the time. Most people that I’ve talked to about this are actually oblivious to the fact that the time on the package is the best time to cook the pasta. Even pastas of the same shape from different brands may have widely varying cooking times. These variances can be due to manufacturing techniques, including pasta-wall thickness.

Pasta companies have a vested interest in you enjoying their product, so they put a lot of time and effort into figuring out just how long each shape that they make should cook. Use an Extra Big and Loud Timer to reap the benefits of their hard work! Get plenty of water boiling hard, add the pasta, and if the box/bag says to cook it for 8-10 minutes, set the timer for 8 minutes and focus on the rest of your dinner.

Saucing pasta

To make pasta that really sings, you have to take the sauce into account. For most sauces, including tomato and cream sauces, it’s best to finish cooking the pasta in the sauce. Set your Extra Big and Loud Timer for one minute less than your target time. Have your sauce simmering on the stove, ready to use when the timer goes off. Grab a measuring cup and dip out a cup or so of pasta water from the pasta pot and set it aside. Drain your pasta and add it to the sauce.

Add about a half cup of pasta water to the sauce and start to stir the pasta together with the sauce rather vigorously over high heat. Cook until the sauce isn’t runny and it clings to the noodles.

Why add pasta water? When you add the pasta water to the sauce, you bring some of that freed starch from the pasta. That starch will thicken the sauce naturally, just like adding corn or potato starch to a sauce will. As you stir the pasta itself into the sauce, you will also agitate more starches off the noodles, adding them to the thickening equation. And as the pasta continues to cook and starches continue to gel, the water that will be available to the pasta will be sauce, and it will actually absorb the flavors of the sauce into the noodles themselves. Done properly, this will yield a silky- textured sauce that clings gently to the noodles. Top it with Parmigiano or Pecorino cheese and you will have a plate of pasta that cost you 78¢, but would cost you $12 at a fine Italian restaurant.

* Salting pasta water is a must. The salt infuses into the noodles as you cook them, flavoring them far more than adding salt afterward can. Imagine cooking bread with no salt, but then sprinkling a little salt on each slice. It’s just not the same. Use about a teaspoon of salt per quart of boiling water.

Pasta al pomodoro recipe

Ingredients

- 2 28 oz cans whole peeled tomatoes (San Marzano are best)

- 4–6 cloves garlic, crushed

- 4 Tbsp olive oil

- 2 sprigs of fresh basil

- salt and pepper

- 1 lb pasta of your choice

- Hard grating cheese of your choice for serving

Instructions

- Put a large pot of water on to boil with 1 tsp salt per quart of water.

- As you wait for the water to boil, start preparing your sauce.

- Crush the tomatoes by hand for a rustic approach, or whiz them in a food processor or blender for a more even consistency.

- Chiffonade the basil by rolling up several stacked leaves and slicing thinly across the roll.

- Heat the olive oil in a sauté pan over medium-high heat.

- Once the oil is shimmering, add the garlic and cook until it just starts to brown.

- Add the tomatoes and basil to the pan and stir to combine. Add pepper and a little salt, but remember that you’ll be adding salted pasta water later, so don’t overdo it.

- Let the sauce simmer and thicken somewhat as you cook the pasta.

- Add pasta to the water, and stir it. Set the Extra Big and Loud Timer for the time indicated on the package minus one minute.

- From time to time, stir the pasta as it cooks.

- When the timer sounds, scoop out a cup of pasta water and drain the pasta.

- Add pasta to simmering sauce along with 1/2 cup of the pasta water. Keep the rest of the cup of water in case the sauce needs loosening later.

- Stir the pasta, water, and sauce together over medium-high heat for 1–2 minutes to finish cooking the pasta and to coat it well with the thickened sauce.

- Serve with grated cheese for topping

By being aware of the thermal realities of your pasta pot, and the way that the starches in it react, and by using an easy and loud timer like the Extra Big and Loud, you can master pasta cookery. It’s a simple food that doesn’t need your stress. It just needs plenty of salty water and a good kitchen timer.

Shop now for products mentioned in this article

I live in the mountains at 7000 feet. Boiling water temperature is lower than 212 degrees. A 3 minute egg takes 4-5 minutes. What can I do?

Tony,

That is a problem for sure! At my elevation (~4500ft) ‘on the box’ times still check out, but you are significantly higher. According to the ThermoWorks Boiling Point Calculator, your water should boil, depending on barometric pressure, at a smidge below 200°F.

Starch gelation happens even in cold water, though very slowly. I”m not sure what the curve looks like on gelation vs temperature graphs, but I would very much like to know! In the end, I would take an empirical approach. First, get a noodle you like, cook it according to the time on the box, and check the texture. If it is still too firm, let it go another minute, then check again, etc, until it’s perfect. Note the difference in times. Then I’d try it with another kind of noodle, that takes a very different time (fettuccine vs angel hair would be a good comparison for this)and run the same experiment.

Because the altitude adjustment is affecting all the noddles the same, I suspect that there will be a linear correlation in times, which is to say I think that if you have to add X minutes to fettuccine, you’ll have to add X minutes to angel hair.

Then just know that you will have to increase all pasta times by the same amount. I’d love to hear your conclusions and I”m sure there are some other high-elevation cooks out there that would also like to hear your results!

Add fresh herbs towards the end of the cooking cycle so that the flavors remain bright. I also use a pinch of red Chile Flakes early on so that you get a brighter taste.

While I hardly ever name a specific product, Hunts Whole Plum Tomatoes are my go-to favorite. Much less expensive and also much more Eco conscious as they don’t need to be transported across an ocean. This would not be true except for the fact that in a number of taste tests they consistently come out on top.

The Eco thing also comes into play when buying Pasta. There is a Canadian producer whose pastas are superb.The pasta is made in Canada and imported here, They ship some of their wheat to Europe where they produce Italian product wheat across to Italy and then Italy ships it back to as pasta. Not very efficient

Thank you for the posts.

Joel,

Good tips on the sauce and the tomatoes! Another way to season the sauce is by adding fresh herbs both early in the cooking and right at the end so that you get both the darker, cooked in flavors and the bright, fresh flavors. I love the chili flakes, too!

I disagree with knowing when the pasta is properly cooked . The suggested cooking times are at sea level and we at elevation have a lower water temperature. Thus, I start checking the pasta at the suggested time by taste and drain when it is all dente. At 5-7000 ft. In elevation, it takes significantly longer tcook

David,

I wonder (see my reply to TOny’s comment) if the time difference scales linearly across all pastas? Have you measured how much longer it takes beyond the suggested times?

Interesting and informative with regard to the history of pasta.

I do cooking classes in my home and the number one topic is usually pasta and how to cook it.

My biggest pet peeve is adding oil to the water. I never, ever would recommend it. The oil tends to coat the pasta and then the sauce doesn’t get to do its job.

Another issue is people don’t salt the water sufficiently. It should taste like sea water. I recommend using 3 to 4 tablespoons of Kosher salt or coarse grey sea salt to 6 quarts of boiling water prior to adding the pasta. Also, never add the salt before the water is boiling because it can pit the bottom of your pot.

I prefer to add the pasta to the boiling water, stir for a minute or so and once the water comes back to a rolling boil I set my timer for exactly 2 minutes. After 2

minutes, I turn off the heat, cover the pot and allow the pasta to “rest” in the pot for the remainder of the cooking time recommend. This makes for a deliciously tender pasta.

One last thing. Stir in a pat or 2 of unsalted butter at the end of your sauce preparation. Butter adds a nice sheen to your sauce and it makes everything taste better.

Jan,

Interesting method! I’ll have to try it out sometime.

Martin,

Thanks for the great information. It sounds right on point, but I have a question. My girlfriend likes to have her pasta served separate with sauce on top. This usually leads to a small pool of water collecting on the bottom of the plate–no matter how well I drain the pasta. Can you tell me what causes this and how to prevent it? Thanks

Ken,

To avoid this problem, make sure the pasta is well drained before plating. But I suspect that the pasta probably isn’t the problem. It’s the sauce. A lot of sauces will leak tomatoey water out once they sit on a straining-bed of noodles. To avoid this, make sure your sauce is well thickened. Using a thickener (roux, starch, pasta water that you cook in the sauce until it thickens) can also help by making the water clingier.

A couple things:

I have never had a problem with pasta boiling over. I guess I just always used a pot large enough.

Never have I heard anyone in any of my travels in Italy use oil in their water. It’s just a waste of oil.

Your ratio of 10 times water to pasta is accurate. As for salt, one teaspoon salt to one quart is not nearly enough. The ratio is simple: 1 to 10 to 100. For every 100 grams of pasta, 10 grams of salt is added to 1 liter of water. Since a liter is approximately one quart, and one teaspoon of salt is about 5 grams, you need double the salt based on this ratio.

All the cooking shows never seem to show the cooks vigorously stirring the pasta with the pasta water, which is the correct method. Thanks for adding that step.

Scott,

I’m not going to say how many pounds of pasta I cooked trying to get it to boil over. With the right pot and enough water, it really is easy to avoid.

The salinity of the water is often quoted as higher than I recommended in the post—”as salty as the Mediterranean”, some say—Thank you for your input on this!

Someone said put oil in the boiling water so spaghetti doesn’t stick. Almost a thousand percent right. The wooden spoon you used to stir the sauce use the spoon with the sauce stuck on it to stir the salted water and pasta! Works every time!