How to Dry Brine a Turkey: Secret to Juicy Meat

By now, we’ve pretty much all learned about the benefits of brining a turkey or any other meat: juiciness, tenderness, flavor…juiciness. But, what if I told you that you could get even more juicy meat without all the hassle of making a brine and keeping meat cool in the watery mixture for a day or two?

No problem.

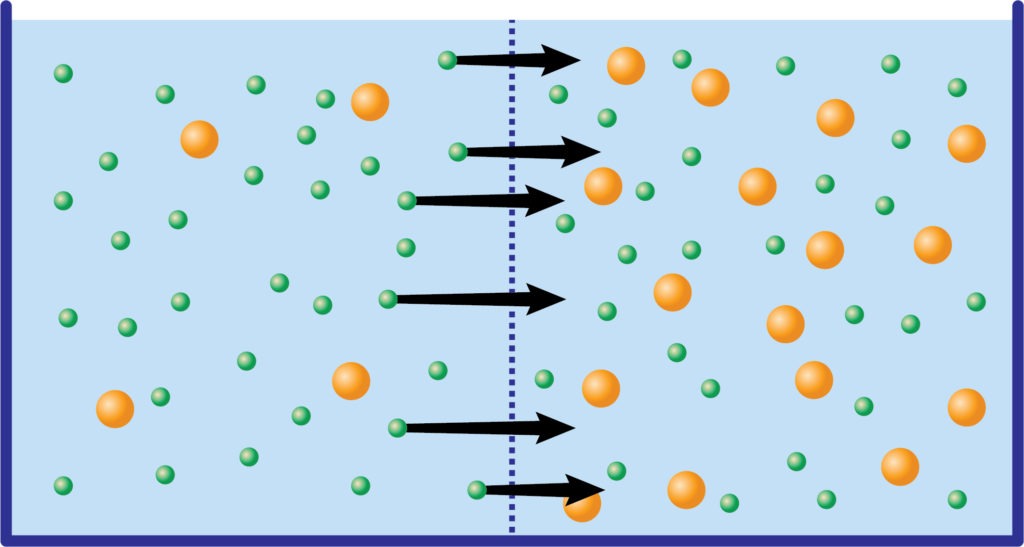

When people talk about brining, they most often refer to osmosis, the movement of water across water-permeable membranes. Water moves from an area of low solute concentration to an area of high solute concentration. Think of it as Nature seeking balance. If area x has one part salt and two parts water, and area y has pure water, water will flow from y into x in an attempt to create equal concentrations.

The theory behind brining is that turkey cells have all sorts of solutes (minerals and proteins, for instance) and that bathing them in a salt-sugar solution will encourage water to move across that membrane, bringing with it some of the salt and sugar to season the meat. The result, supposedly, is that the meat ends up juicier.

In truth, this is not what happens.

If it were, then soaking a turkey in pure unsalted water should be more effective than soaking it in a brine…Moreover, if you soak a turkey in a ridiculously concentrated brine…according to the osmosis theory, it should dry out even more. —Kenji, pg 575

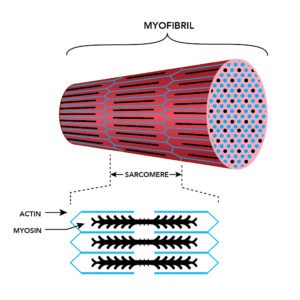

So, what is really happening when we brine? Salt action. Before I explain, let’s talk some about what happens when we cook meat. In our post, Heat and Its Effects on Muscle Fibers in Meat, we showed that myosin denaturation is responsible for most moisture loss in meat: when the myosin molecules in protein fibers shrink under heat, they squeeze water out of the muscle fibers.

This is where the salt comes in. Salt actually allows myosin to dissolve, preventing later coagulation. If myosin can’t coagulate, then it can’t get as tough when cooked and it also can’t squeeze as much water out of the protein fibrils—allowing them to retain moisture better. So, treating meat with salt promises more tender meat that is also more juicy.

“Yes,” you say excitedly, “that’s why I should brine my meat in salty water!”

“No,” science frowns back at you, “that’s not what I said.”

If we look carefully at what’s happening, we see that the salt is actually doing the work, not the water. In fact, the brine solution itself has some distinct disadvantages. One is that it is literally watering down your meat. By bringing water into the meat, you are diluting its natural flavor, making densely packed amino acids more scarce per gram of food. Not good.

…brining robs your bird [or meat] of flavor. Think about it: The turkey is absorbing water and holding on to it. That 30 to 40 percent savings in moisture loss is not really turkey juices—it’s plain old tap water. Many folks who eat brined birds have that very complaint: it’s juicy, but the juice is watery. —The Food Lab by J. Kenji López-Alt (pg. 576)

Of course, another disadvantage is that it’s a royal bother. Brine solutions are heavy and messy and raw turkey brine is not something you really want contaminating your kitchen.

So now we arrive at the advantages of a dry brine. Dry brining could just as easily be called “salting,” which it is (but that has connotations of preserving and drying that we’re trying to avoid). The salting/dry brining process accomplishes everything good that a wet brine does. As the Cook’s Illustrated Meat Book describes:

When salt is applied to raw meat, juices inside the meat are drawn to the surface. The salt then dissolves in the exuded liquid, forming [its own] brine that is eventually reabsorbed by the meat. The salt changes the structure of the muscle proteins, allowing them to hold on to more of their own natural juices. —Cook’s Illustrated Meat Book (pg. 5)

So there you have it. The perfect solution for both dissolving myosin and retaining more of the natural juices of your turkey. It’s like having your cake and eating it, too (except in this case, you’re eating turkey).

To dry brine a piece of meat, rub it well with kosher salt and give it a rest. The time needed for the process varies based on what the meat is. Below we’ve recreated a table from the Cook’s Illustrated Meat Book explaining the amount of salt and the time needed to dry brine various meats. A timer like the TimeStick can help you keep track of your dry brine.

| Cuts | Time | Kosher salt | Method |

| Steaks, Lamb Chops, Pork Chops | 1 hour | ¾ tsp per 8-ounce chop or steak | Apply salt evenly over surface and let rest at room temp, uncovered, on wire rack set in a rimmed baking sheet. |

| Beef, Lamb, and Pork Roasts | At least 6 hours or up to 24 hours | 1 teaspoon per pound | Apply salt over surface, wrap tightly with plastic wrap, and let rest in refrigerator. |

| Whole Chicken | At least 6 hours or up to 24 hours | 1 teaspoon per pound | Apply salt evenly inside cavity and under skin of breasts and legs and let rest in refrigerator on wire rack set in a rimmed baking sheet. (Wrap with plastic wrap if salting for longer than 12 hours.) |

| Bone-in Chicken Pieces; Boneless or Bone-in Turkey Breast | At least 6 hours or up to 24 hours | ¾ teaspoon per pound | If poultry is skin-on, apply salt evenly between skin and meat, leaving skin attached, and let rest in refrigerator on wire rack set in a rimmed baking sheet. (Wrap with plastic wrap if salting for longer than 12 hours.) |

| Whole Turkey | 24 to 48 hours | 1 teaspoon per pound | Apply salt evenly inside cavity and under skin of breasts and legs and let rest in refrigerator, uncovered. |

This table reflects the significance of the idea that the salt—drawing out juices—creates a natural brine. By wrapping the meat in plastic wrap, that brine is held in place next to the skin, allowing it to be quickly reabsorbed. Kenji López-Alt, however, recommends putting chickens and turkeys in the fridge without wrapping them, noting that a crispier skin will result from the skin being able to dry out overnight.

To dry brine a bird, first carefully loosen the skin…Then rub about 1 teaspoon of…kosher salt per pound of meat all over its body, under its skin. Place the bird on a rack set over a large plate or rimmed baking sheet and refrigerate uncovered, overnight (or for up to 48 hours if using a turkey. The next day, cook as directed, skipping or going light on the seasoning step. —The Food Lab by J. Kenji López-Alt (pg. 579)

In our experience, wrapping the meat is not necessary, and leaving it open to the air in the fridge yields excellent results. (We followed this method, for instance, in our How to Make Fried Chicken: Deep-Frying Thermal Tips post.) The brine created by the extracted juices still rests on the surface of the meat before being reabsorbed.

(It is, of course, extremely important that your chicken/turkey/beef stays at or below 40°F(4°C) in your refrigerator. Much like an oven, refrigerator temperatures can be wrong or fluctuate wildly. Check the accuracy of your fridge’s settings by using a ChefAlarm or an infrared thermometer like the Industrial IR Gun.)

Wrapped or not, by salting the meat directly it is easy to achieve the 5.5% salt solution in the meat that is necessary for partial filament and protein structure dissolution (On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee, pp. 155-156). That means more tender, juicy meat!

If you’re concerned about losing the flavor you were hoping to get from your brine, don’t be. You can make a rub with a high salt content and use that on your meat for the dry brine. This will give the flavors time to soak in and you will actually get a more direct, pronounced flavor from them than in the wet brine.

This Thanksgiving, give dry brining a try. Or try it on your Christmas roast! A dry brine is miles easier than—and every bit as effective as—a wet brine. No buckets needed, and you still get the protein-dissolving power of salt to make your meat juicier, more tender, and plain tastier. You’ll need to allow an extra day of preparation after your turkey has fully thawed, but it’s worth it.

Products:

References:

Harold McGee, On Food and Cooking: the Science and Lore of the Kitchen

J. Kenji López-Alt, The Food Lab

America’s Test Kitchen, The Cook’s Illustrated Meat Book

There was no mention of rinsing the meat after brining. Required or not? I can’t imagine not rinsing.

Thanks.

Dave,

I do not rinse. You want to use enough salt to get the job done, but not so much that it’s caked on. The amount put under the skin and on the skin is not too much. The skin comes across as salty, almost like bacon, but not inedible by any means. If you feel it is too salty, by all means give it a rinse and them pat it dry very well. I recommend trying it without rinsing. The dozen or so turkeys I’ve made this month have all come out well without it.

Good luck and let us know what you decide and how it goes!

Martin,

It all sounds good…but what are the implications for those of us who may be on low-sodium regimens? Doesn’t dry brining (or wet brining, for that matter) result in a saltier protein and therefore a higher amount of sodium in our food?

–bill

Bill,

Your bring up a good point. It is unfortunately true that dry brining will increase the sodium content of the meat. If you were able to cut salt from another dish (your dressing?) where others can easily add it in and have all the salt you can in the turkey, that might work.

If your restrictions are very tight, it can be more of a problem, but there are some workarounds you can try. Meat dries out when muscle fibers constrict during cooking. If we haven’t dissolved the myosin then the higher the temperature, the harder they squeeze. By cooking your bird at and to a slightly lower temperature and holding for the proper amount of time, you can get a juicier bird than you would at full-fire. Perhaps not as juicy as with the brining, but better than it would otherwise be.

If you’re concerned about losing the flavor you would get from the dry brine, be sure to stick a few minced hers and maybe even some crushed garlic up under the breast skin and in the cavity of the bird. You will have delicious results from that.

There are natural tenderizers that will breakdown some proteins that might help (papaya chief among them) but they don’t generally mix with the flavor of Thanksgiving.

Unfortunately, nature has not provided us with an excellent salt substitute that does all the same things, but I hope these tips can help.

Good luck!

Besides kosher salt can I use other seasonings too with the dry brine?

Grace,

By all means, you can add other seasonings! This is part of what a barbecue rub does: add flavor and salt for tenderness. Personally, I like to make a compound butter with herbs and whatever spices I want and put that butter up under the breast skin before cooking. I find that to be a great means of flavor delivery.But adding them with the salt is a great way to infuse more flavor into your turkey.

Good luck and feel free to tell us how you season your bird!

I find the skin tightens after dry brining. Can you still get the butter rub under the skin without tearing it? Or can you just mix the salt with butter at start of dry brine or will that interfere with re-absorption of moisture?

I’ve never had much trouble getting the butter in under a brined skin.

How does this affect those on a salt restricted diet?

Please see the response to Bill below.

I tried dry brining steaks once and they came out extremely salty. I rinsed off the salt, but the result was a couple of nice steaks that were too salty to enjoy. I did likely use more salt than you recommend, but I’d think it could only re-absorb so much brine.

Also, you make no mention or rinsing the meat. I assume you leave the salt on it?

Mark,

Meat can absorb an impressive amount of salt, so using the recommended amounts is really best. You are correct that I do not rinse the salt! Much of that salt I use in a dry brine goes under the breast skin, making it not only unnecessary but also logistically difficult! The salt will continue to season the bird as you cook, basting the bird from under the skin, and the salt that is rubbed on the skin will make the skin taste bacon-y and delicious.

Rinsing will also re-introduce water to the skin that we have sought to dry out overnight, eliminating our edge in the hunt for a crisp skin.

So, good luck with your next dry brine and happy cooking!

So what if your brine is not just salt and water? I use salt, sugar, herbs, and spices. How will you get the other flavors in there? I can see doing it to steaks chops and roasts. I would have to try it out. Turkey is bland to me anyway and just adding salt doesn’t sound like it will help it as much as a good brine.

Joseph,

You have a point, but there’s nothing I can think of that you put in a brine that you can’t do in this method. You can, if you want, add spices and herbs to the salt when dry brining, and those flavors will infuse in an even more intense way. This is, in essence, like a barbecue rub.

You can also make a compound butter with any and all flavors that you want and tuck it up under the breast skin right before cooking. (I also tuck a little of it between the leg and body and the wing and body.) To me, the intensity of flavor introduced and the ease of dry-brining far outpace whatever qualities I had found in a wet brine.

Give it a try and let us know your findings!

Will the dry brining result in salty gravy derived from the juices of the dry brined bird?

Doug,

Good question! If you use the recommended amount of salt, this should not be a problem. Not enough salt escapes into the juice that comes out of the bird to oversalt the gravy, which requires added liquid. Of course, you will want to check your gravy’s seasoning before adding any salt called for by a written recipe; but there isn’t any danger of overdoing it just from the dry brine.

Let us know how it turns out!

Do you have a good compound butter recipe for a turkey that has already been dry brined?

Harvey,

Sure! I use 1 cube (1/4 lb) butter, softened, and mash it together with a teaspoon each of minced sage, minced rosemary and stripped thyme leaves, about 1 tsp black pepper, and sometimes a dash of paprika. A little lemon zest in there is also a great addition. Use whatever you think will make your turkey tasty, and good luck out there this week!

What if your turkey is injected with broth (8% solution) should you not use dry brine? Or maybe use even less of the dry brine?

Lisa,

Good question. I would still dry brine. That 8% broth is 8% of the turkey’s weight, not an 8% salt solution. And since we’re looking for a rough-estimate brine concentration of 5.5% salt, that means the injected brine would have to be almost 69% salt—well, beyond the saturation point. The reason mostcompanies inject a brine into the turkey is as an insurance policy against the customers overcooking the bird, and they use a broth because using straight water is a terrible idea. There isn’t enough salt in it to do the kind of protein dissolution we’re looking for.

You are correct that you might want to use a little less salt in the dry brine, but I have had tremendous success dry brining-without modification-turkeys that have been injected. I myself am cooking a pre-injected bird, but will be dry brining it at full strength.

Good luck and let us know how it goes!

Would this method work for a suckling pig? I’m not certain how to mimic rubbing the salt between the skin and the meat, as separating the two would probably not work on a suckling pig.

A.

Ooh! FUN! I would certainly try this as far as possible. Rub down the outside well with salt (perhaps scoring the skin lightly?), and salt the cavity well. I know suckling pig isn’t exactly cheap, but it would be fun to try separating the skin. If you slit the skin behind the neck and basically ran a boning knife around the inside of the skin—much like deboning a whole chicken for stuffing—you might be able to do it. If that were to work out, putting some thin apple slices under the skin would be a great way to season the pig for roasting too!

Thanks for the exciting question, and let us know shat you decide to do and how it works out!

Rinse pig, dry pig thoroughly. Score the skin of the pig w/utility knife (don’t go into the meat) every 1.5″, it should look like a checkerboard when finished. Rub down 1/2 salt, 1/2 baking soda mix all over skin and into the cuts. Refrigerate 24hrs on a rack. Rinse and dry thoroughly. Reapply salt (or rub) as desired, leave countered for 1-2hrs. Cook initially at high temps (hot flash) the shoulders and hams until they begin to blister (5-10min) then turn the heat down to 275. At ~1/3 the cooking time, hot flash the belly/loin (middle), then turn down to 275 until done. The cooking art is in getting the science right (>190 shoulder, 145 loin, and 165 ham).

Pro tip: When breaking down the pig, remove the crackling from the ribs, quickly wrap them in foil with butter, honey, brown sugar and put them on a 300 deg grill (indirect heat) until meat shrinks from bone 1/4″ (190-195deg). Good luck

Hi there

I have to say thank you for such a thorough demystifying of an important part of everyone’s year. After 20 years as a commis even I got a couple of tips. Well done and happy thanksgiving 🦃